I recently presented the latest installment of PAYETTE’s Architecture Forum, a discussion outlet the firm developed in 2005. It was envisioned as a professional discussion group focusing on architectural design issues in practice. Each 20-30 minute forum presentation is followed by open discussion. Presentations provide a concise focus for the ensuing discussion and will draw on photographs, drawings and diagrams of examples that will seek to encourage exchanges of ideas rather than to simply provide information.

I invite you to download the full presentation here.

My forum examined photographic perception, as interpreted through the built environment. I argue that buildings and cities provide a fruitful context for this fundamental examination, because though they are not static, they ‘move’ within spatial and temporal fields that exist substantially outside the range of our own perception. Architecture can be understood through a still moment of a photo; a work of art that is nevertheless “consumed by a collectivity in a state of distraction.”[1] To identify a work of architecture as the subject of an artful photo can add value to an otherwise insignificant corner of the world which can seem to be ‘invisible’ to us distracted humans.

I’ll use this post to discuss one additional work that I hope will illustrate my argument. This is a photograph of the Barkin Levin Plant in Long Island City, Queens, NY, designed by Ulrich Franzen, and shot by famed architectural photographer, Ezra Stoller. It is a little known image of a relatively insignificant specimen of mid-century high modernism.

Photo Credit: https://www.instagram.com/stollerized/

Contemporary images of this structure reveal diminutive scale, a questionable later addition, a new intrusive hedge and an ad hoc context of light-industry that conspire to contest its sustained (and past?) claim to “architecture.”

Photo Credit: Queens Modern

Photo Credit: Queens Modern

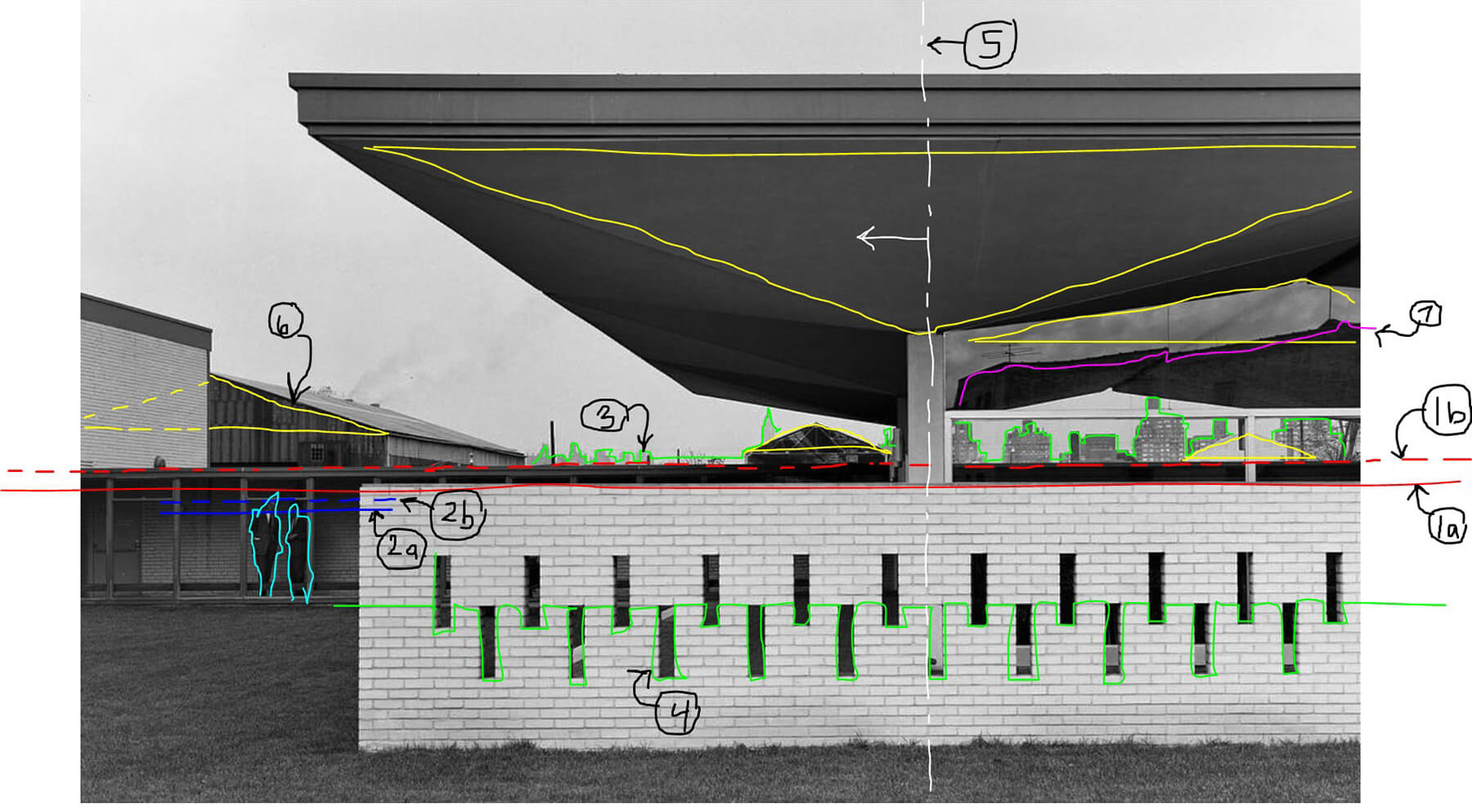

Through the medium of photography, however, Stoller uses this context to conduct a thorough blending of human and material time and space. The results are complex and surprising:

Stoller aligns his camera’s horizon (1a) to the top of the foreground brick wall. In fact, this is slightly lower that the building’s own “horizon”—its low roof line, (1b)—which is superimposed on our view as a strong crop of the skyline (3). The duplicate horizon is the most important compositional element; it stratifies the scene into terrestrial and atmospheric realms, perhaps to complement the intention of the architect. Once hierarchy is established, Stoller aligns the camera vertically with the first column of the folded upper roof (5). He then shifts his view camera’s film plane to the left, coaxing the low roof line leftward and down into the glazed portico—all while maintaining a dry orthogonality.

This last move affords Stoller the opportunity to locate two doppelgangers in the left middle-ground, gazing back at the camera (back at us). Their horizon, like ours, comes in duplicate: a transom (2b) divides their perspective just above eye level (2a) much as the low roof line bisects the camera’s. Thus, as empathetic viewers, we are invited into the image twice.

After our introduction to the terrestrial space of the building, our view meanders up toward a space of levity and scaleless-ness sanctioned by the persistent low roof crop. Squat triangular pediment forms proliferate at different scales here. They form graphic signifiers of the vernacular industrial shed, but also oscillate in their reference to something more sacred: the classical temple front. The plant roof itself inverts this triangular form to reveal and compress the visual space of the skyline (3), but also to pick up another skyline in the glass’s reflection of the view behind us (7). Reference to this phenomenal mirroring is made through a deliberate pictorial one: the inversion of the distant skyline below the horizon in the form of the brick screen’s pattern of voids (4) as the eye is returned to the foreground.

Through a careful and thoughtful composition, Stoller pulls us in, through, across and out of these spaces and the surrounding city. My argument is not that this trajectory is impossible without photography. Rather, I contend that photos provide an occasion for us to acknowledge and transcend the myopic limits of our own distracted perception.

[1] Benjamin, Walter, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, 1936.