Details take us into the realm of the architect’s highest possible resolution of drawing. When the process is well-practiced, we find in it the opportunity for innovation and the ability to express deeper creativity. And we as designers know, details are fundamental to the life and personality of a project.

We had the privilege of reviewing over one hundred of our firm’s details and in doing so asked what do these details have in common and is there a thread or theme for various project types? One way of seeing details is as the constitution of boundaries between different materials, between the internal & the external and even as elements that begin to distort and blur the boundaries of a building itself. A barrier, as some define it, is something material or immaterial that impedes or separates. We looked at details as barriers in four different ways.

The first and most basic form is as weather barrier. Basic in the sense that every building must meet certain standards pertaining to waterproofing and insulation, but complex, as our own standard practice is to design the highest performing building envelopes possible. The second, more specialized form of barrier is as shielding barrier – protecting occupants or program from the elements or other factors. (For instance, we all wish we could ‘attenuate’ that certain next-door neighbor.) The third is the act of breaking barriers. In this case, details that perform the task of adjoining a new building or condition to an existing one. And last are details that go beyond the mere function of barriers and into their overall impact. These are a category where the synergistic effect of carefully crafted details can profoundly influence sensory perception at the level of the building as a whole.

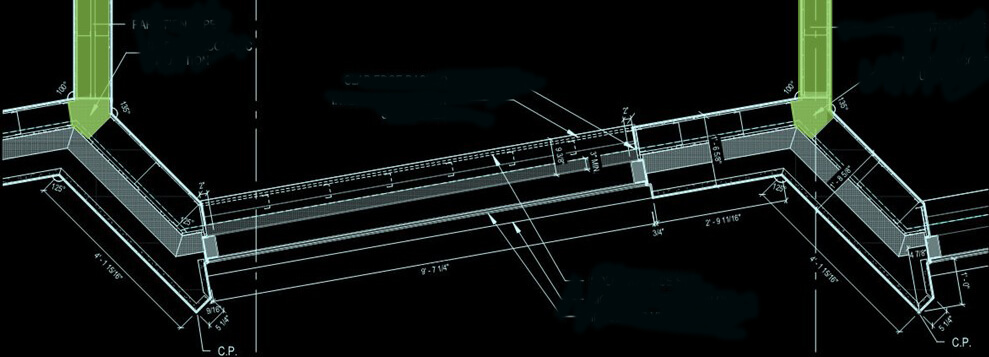

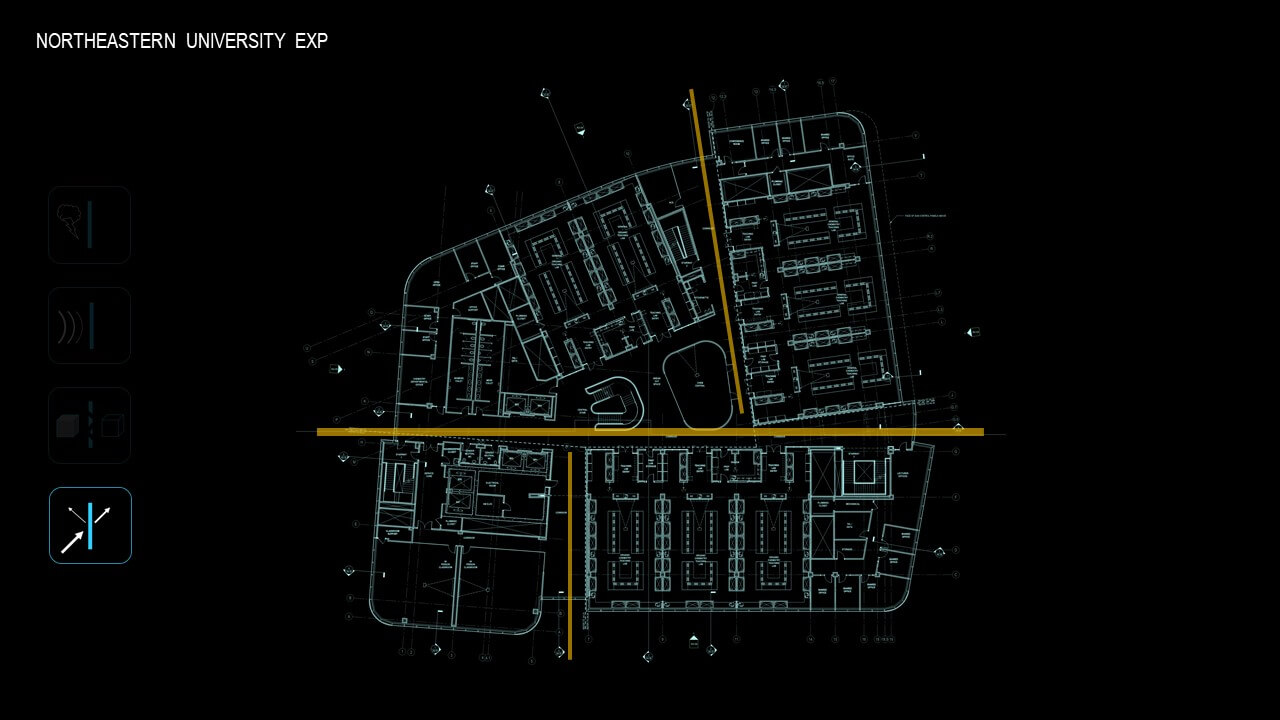

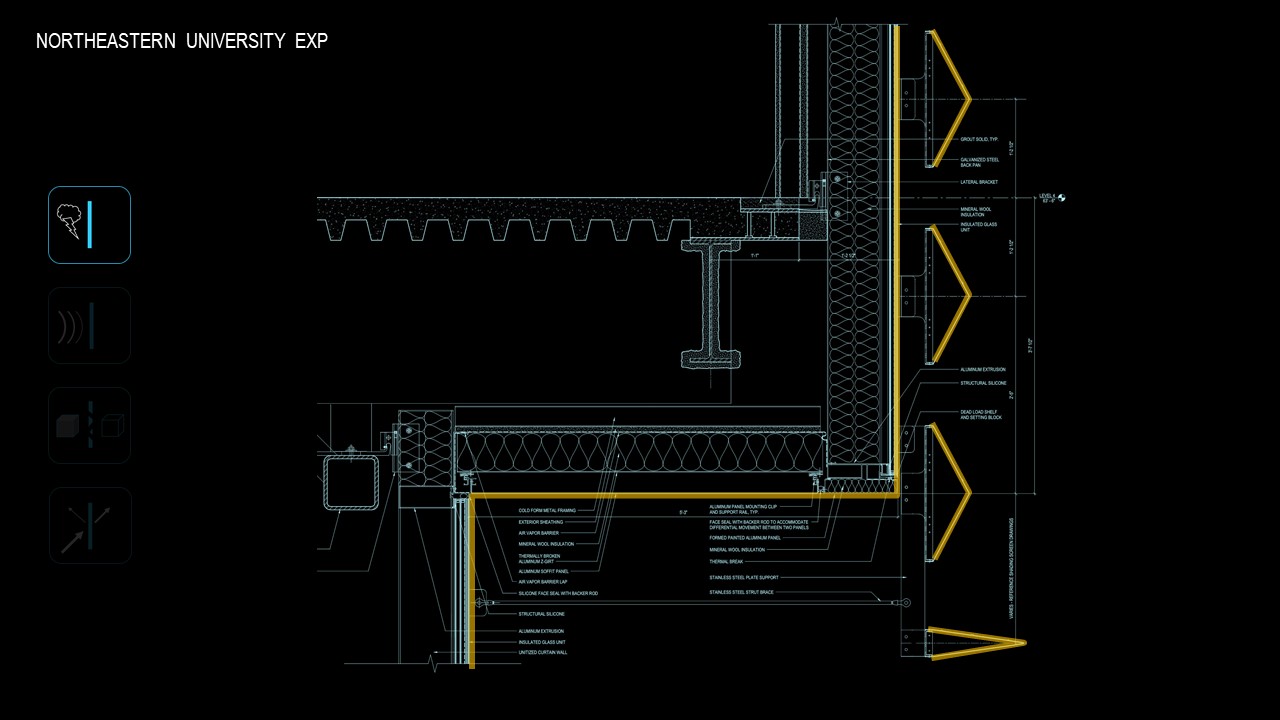

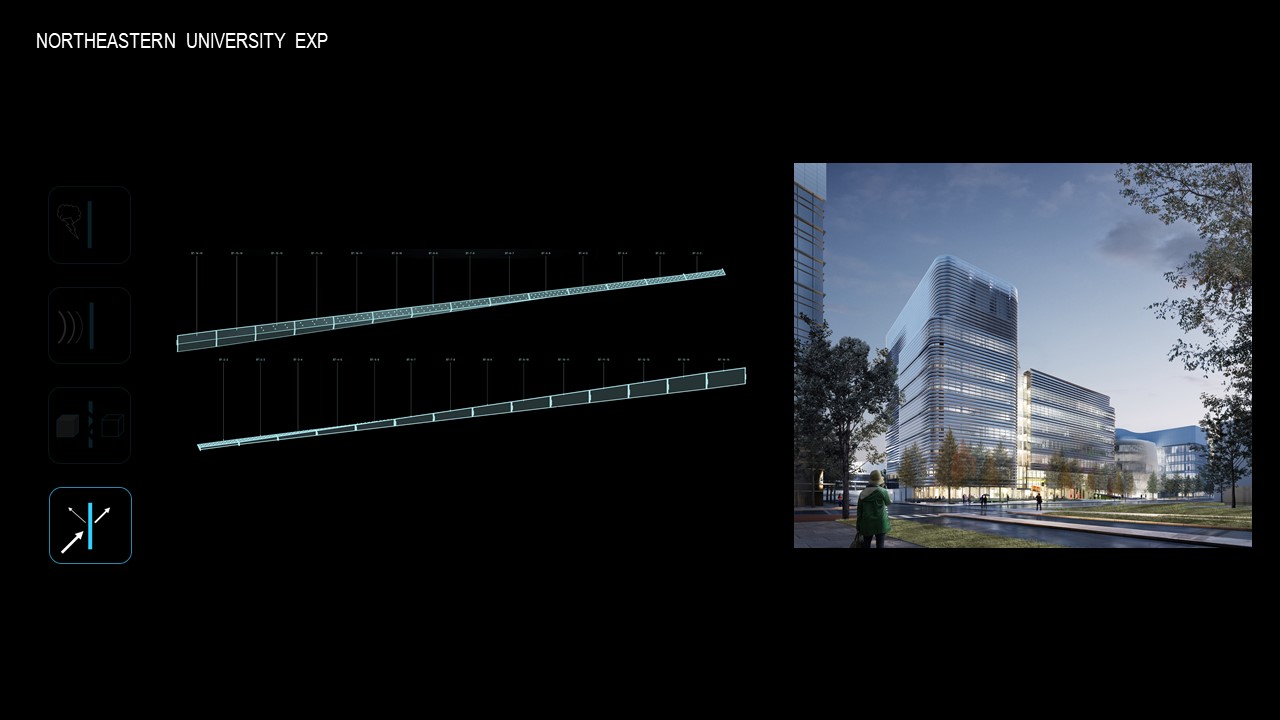

In some cases, a building’s exterior responds directly to its interior configuration. The EXP at Northeastern University uses a pinwheel layout resulting in circulation datums which influence the behavior of the exterior sunshades. A series of folding panels limit solar exposure and visual sight by increasing or decreasing the vertex angle. However, beyond the weather barrier aspect is an intricate set of parameters – parameters that organize panel types and can even streamline fabrication. Each panel follows a set of rules – increasing the height decreases the depth, increasing the depth decreases the height. The result is an exterior skin that responds not only unto itself but also to the complex.

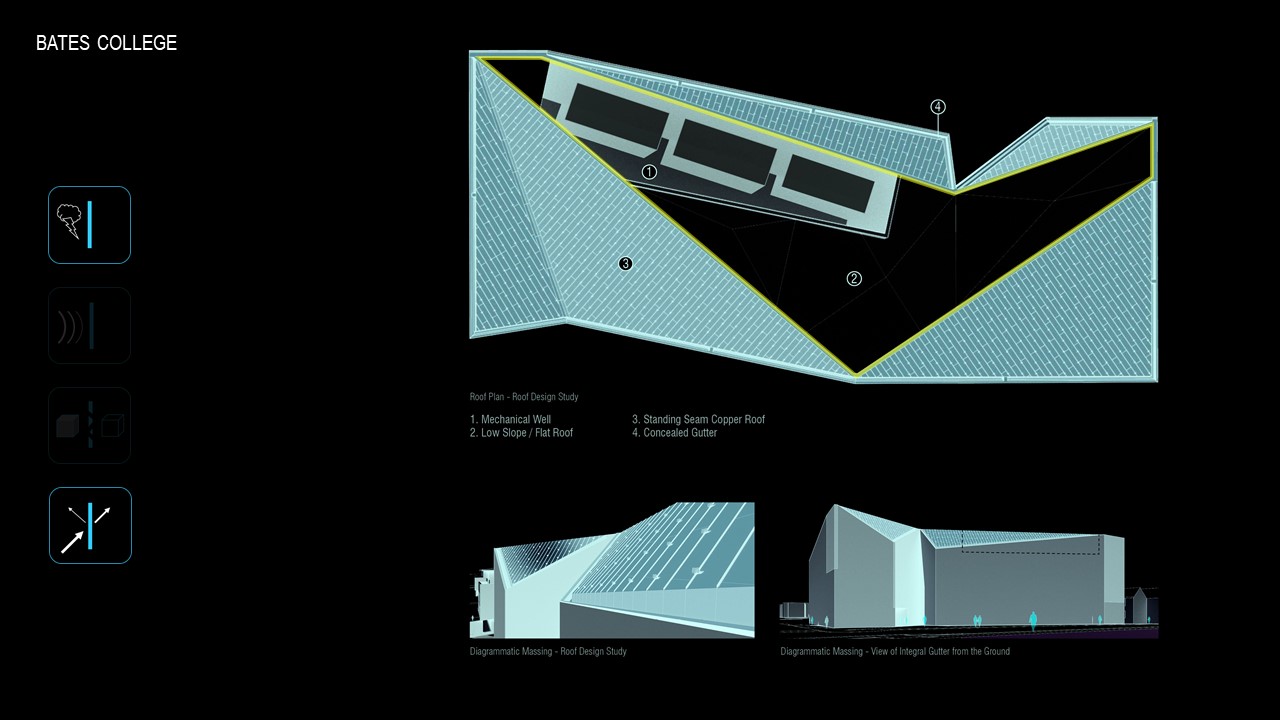

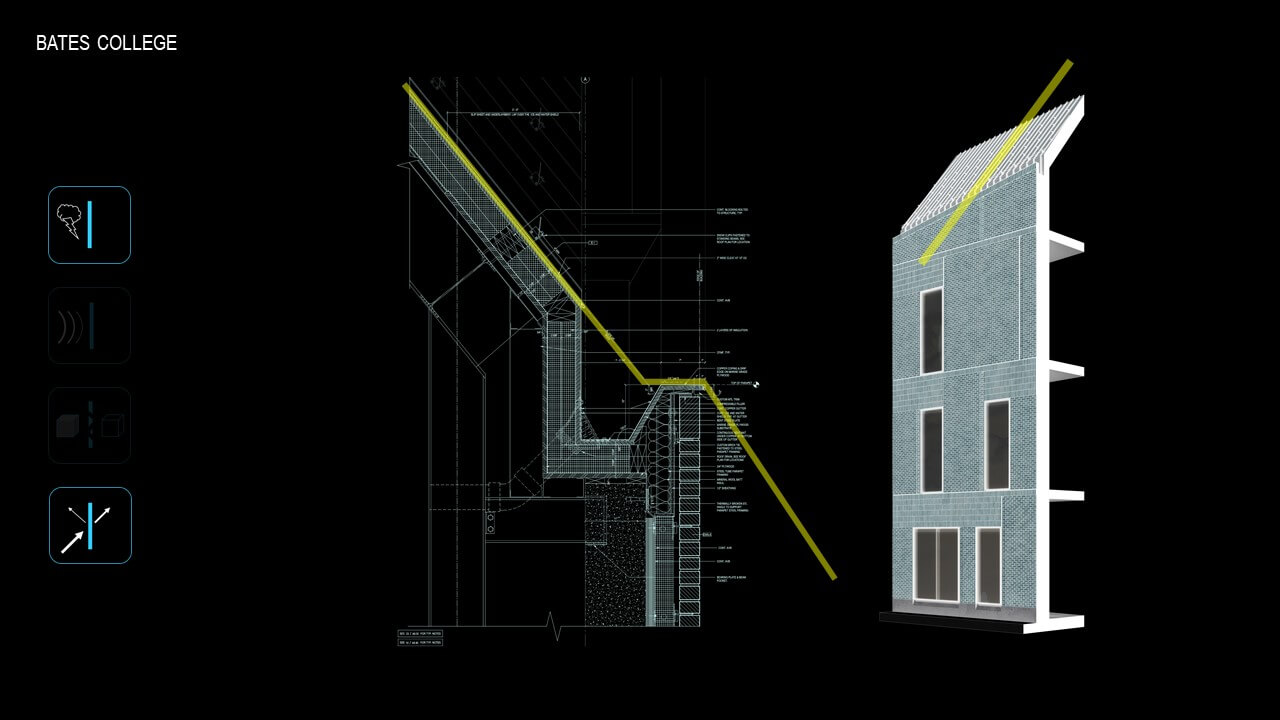

The perimeter of the Bonney Science Center at Bates College features a roof that conceals a robust snow and ice management system. Without projecting overhangs, it conceals a large mechanical equipment well and penthouse. The roof and parapet details reinforce the reading of a singular building mass. The detail describes a copper roof and coping with a continuous copper gutter. The steep roof causes water run off to reach such velocities that without offsetting the parapet, water would move over the gutter. The size of the gutter was therefore in direct relationship with the angle of the roof, but visually the detail is perceived as if it were a uniform sloped roof.

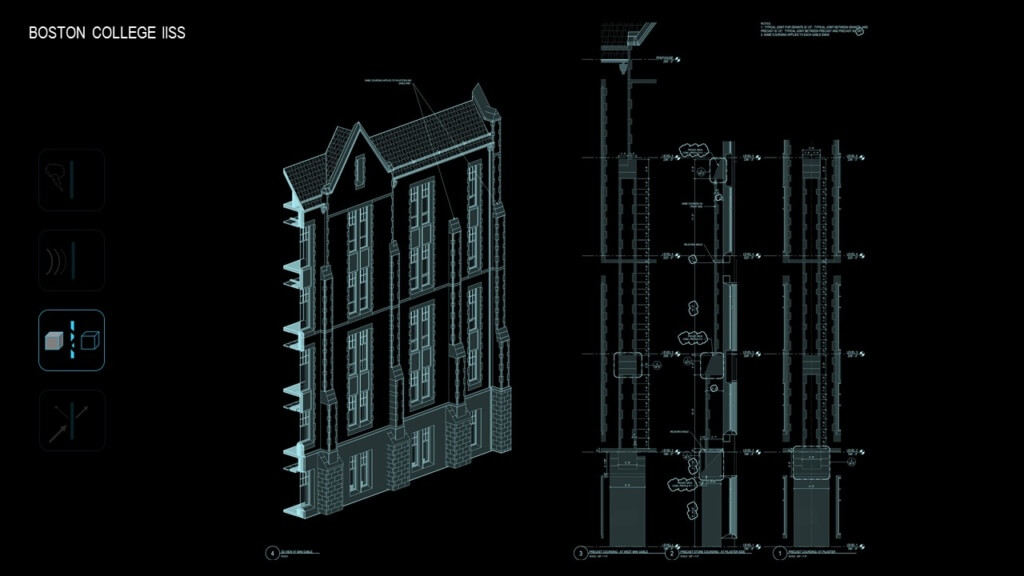

The Schiller Institute for Integrated Science and Society at Boston College is unique among projects in the office, with a traditional stone façade that houses a modern college of engineering inside. The challenge here is building on a dense site and connecting to an adjacent building on two levels.

Boston College is proud of their school’s traditions and spirit, and their buildings express this. Although similar in fashion, they are built in different decades. The façade of the new IISC maintains this spirit – but embraces modern engineering and architectural detail. The detailed façade drawings produced by the team set the stage for the materiality of the new building. Using granite from the same quarry Boston College sourced for other recent buildings on campus assures the stones will be of the same pallet. A mockup will be constructed on-site to show how the stone, precast, roof, and windows all are in keeping with the traditional campus architecture – while breaking the barrier between old and new.

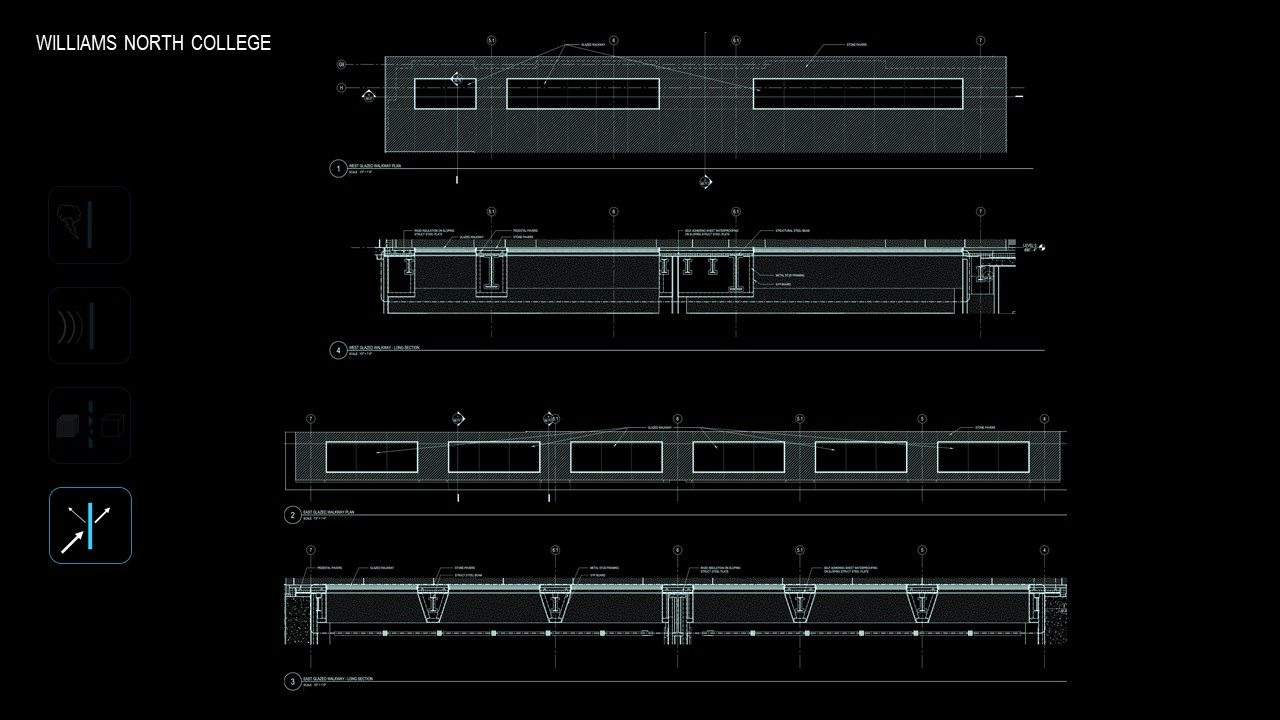

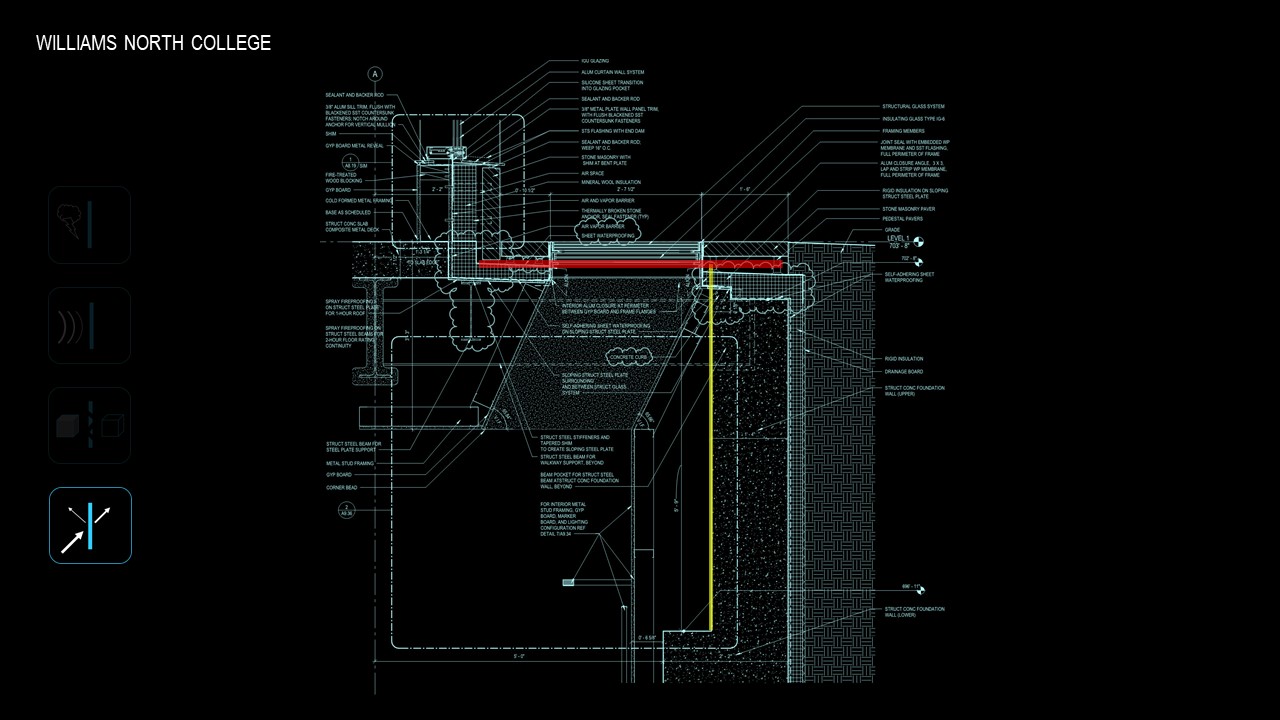

At Williams College the simple idea of a skylight goes beyond barrier and creates a bit of mystery with sidewalk “pavers” that are skylights. A simple idea, but complex in how it performs. Science dictated the sizes of the opaque skylights, creating a pattern with three sizes that generates a rhythm around the building structure. It is the details that bring this elegant design to existence. The most creative, elegant, and innovative details always come with their revisions. These types of details are unique solutions to specific problems. This is a symbol of trying something new and working with the builder to fabricate an idea into existence.

As we have seen, details hold the potential to characterize and sometimes even to define an entire building.

And while things like waterproofing and continuous insulation are absolutely integral to the building’s longevity, occupant comfort and performance, that is scratching at the surface of what a detail can and should convey. Details are a constitution of barriers of what – we as architects and designers – use to delineate separation, unify form, shield programs, and shape perceptions. Let’s go beyond the mere utility of these barriers and into their potential architectural effects upon our senses.

Related Posts:

Construction Update: Williams College

YDC Tour: Onward and Upward – Renovation and New Construction at Boston College