Hundreds of designers, architects, planners and students flocked to Nashville, Tennessee for NOMA’s 2022 National Conference “Unplugged.” Now three years post the onset of COVID-19, attendees relished the opportunity to celebrate, learn and ultimately reconnect face-to-face. “NOMA,” or the National Organization of Minority Architects, was established in 1971 by twelve African Americans eager to expedite the development and advancement of minority architects. Today, NOMA is comprised of roughly 2,500 members distributed across the globe.

This year, PAYETTE People Larissa Sattler and Calvin Boyd decided to “unplug” and participate in the conference. Read on to hear exciting snippets from several sessions they attended focused on EDI in architecture, community engagement in design and equity-centered research in practice.

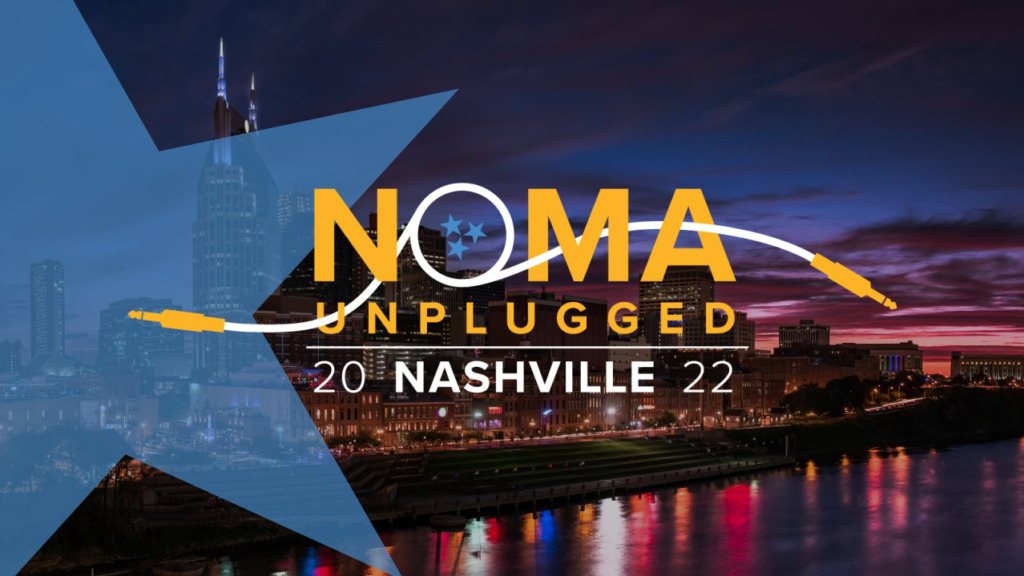

Where Are My People? Race in Architecture

In this session, Kendall Nicholson, Director of Research & Information at the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA), presented the ACSA’s current research related to the expression of racial narratives within our profession. Key takeaways included:

- An updated definition of equity: the reallocation of resources that recognizes history and systems.

- Architecture admissions is not the central issue hindering diversity, rather it is a lack of candidates (one reason being the continued criminalization of African Americans who account for 32% of the US prison population but only 6% of the total US population).

- Most African American students are enrolled in pre-professional programs while white students are primarily enrolled in professional degree programs.

- African American women account for two-thirds of total Black students in higher education, but only one-third of Black architecture students and one-fifth of Black architects.

- Hispanic and Latinx individuals only account for 8.7% of architecture faculty, 6.7% of architecture award recipients and 5.9% of AIA members despite being 18.5% of the US population.

- The architecture profession is often seen as incongruous to people that value family and close relationships like Hispanic and Latinx individuals. For some racial groups there is a conflict between architecture and their value systems.

- US architecture programs with the largest Indigenous enrollment are the University of New Mexico, the University of Arkansas and Oklahoma State University.

- More data points regarding individuals in architecture that identify as Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) is needed. This group is often classified as white in the census and in architecture schools?

- The success of a particular minority group does not negate the history of injustice against them (within and outside of our profession). The “model minority” myth often ascribed to students of Asian descent is harmful.

Where Are My People? is a research series that investigates how architecture interacts with race.

Image Credit: Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture

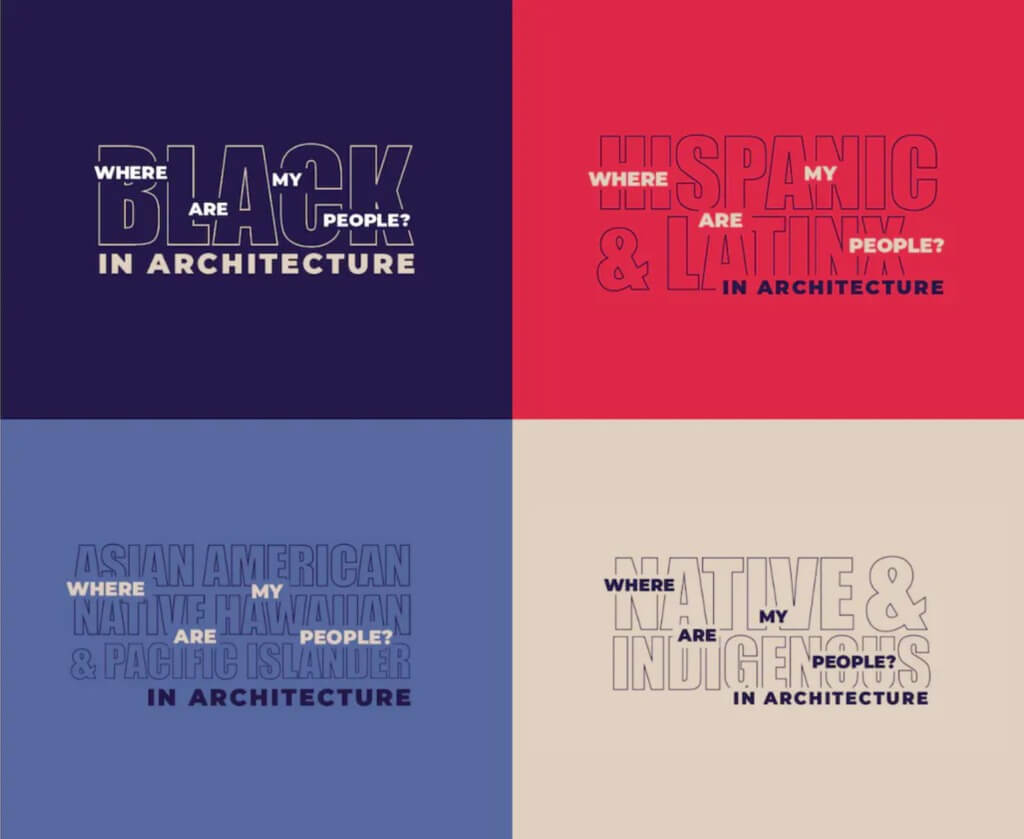

Place Driving Equity: A Guide for Action

Panelists in this session shared “lessons learned” from the recently released “Reimaging the Civic Commons” guide, a tool to help architects advocate for place-based interventions and build trust in their local communities. The community engagement processes for a few projects were described and critiqued. Key takeaways included:

- The primary reason for inequity in our communities is disinvestment.

- Wealth-building is necessary to create lasting change. Certain racial groups often do not have the resources to retain their communities once they are invested in.

- Black families in the U.S. have a median wealth of $24,000 while white families have a median wealth of $188,000.

- Highways, major transit systems and industrial zones have historically been driven through communities of color, leading to disinvestment, poorer health outcomes and a gulf of mistrust.

- Aim for co-creation in design. Design “with” community partners, not “for them” or “to them.”

- Ultimately, socio-economic and cultural mixing should be the goal. A lot of the case studies in the guide attempt to redefine the types of positive interactions people can have in public parks.

The national initiative to advance ambitious social, economic, and environmental goals began in five “demonstration” cities: Akron, Chicago, Detroit, Memphis, and Philadelphia.

Image Credit: Place Driving Equity Guide

A Nashville Justice Facility Case Study

In this session, Kimberly Dowdell (HOK) and Jonathan Moody (Moody Nolan) presented the design for the recently completed Davidson Metro Criminal Justice System. The presentation sparked many questions about the project’s inventive and economical design as well as questions regarding the ethics of prisons. What is our responsibility as architects, and is “good design” alone enough to build a just world? Key takeaways and questions included:

- Should the loss of one’s freedom also mean the loss of access to quality architectural spaces?

- Are publicly sponsored prison projects more ethically sound than private ones?

- Could the prisons we build or rehabilitate in the present be adapted for a new purpose in a future with far less incarceration?

- ArchiPAC, the AIA’s political action committee and lobbying group, is extremely underfunded. For architects to influence political decisions regarding incarceration, this may need to change.

- Many firms that indulge in the design of prisons cite the AIA Code of Ethics Ethical Standard 1.5 which details that members should not knowingly design spaces intended to execution and members shall not knowingly design spaces intended for torture.

- Ethically, is the bar high enough? The development of prisons was a direct result of slavery in the U.S., and their very nature upholds systemic injustice. Additionally, in the age of climate change it is becoming increasingly important to be selective about what carbon-intensive buildings need to be built at all.

Davidson County Criminal Justice Center in Nashville, TN

Image Credit: HOK

Research in Practice

The Center for Research on Equity and the Built Environment is a relatively new initiative within Gensler’s Research Institute. In this session, Lisa Cholmondeley and Roger Smith presented some of the latest findings and initiatives being researched. A key part of this discussion came from an opportunity for the audience to interface with a large firm such as Gensler who has the means and methods to push out large quantities of high caliber research. Questions were raised such as how do small and mid-sized firms who are interested and passionate about doing research in practice find the means and funds to do so? How do firms find and engage with research that already exists? And the big question-how is this research applied in practice and how does it influence project work? Below are some selected projects that were discussed:

The “City Pulse Survey 2022” contemplates if we should rethink everything after the pandemic.

- Focusing on topics around affordability, work and safety, this survey considers “who feels safe?” and “who is living paycheck to paycheck?” Disproportionately, people with disabilities and minorities feel unsafe and are living paycheck to paycheck.

- The survey anonymously polled 12,500 residents across 25 cities around the world.

- It acknowledges that the hybrid working environment has for better or worse complicated how people think about their cities in terms of affordability and attitudes toward amenities

“Fostering Community Co-Creation” is a research project in process but is still valuable to share in terms of better understanding how to develop a model for co-creation and community partnerships.

- The main question focused on “How do you partner with communities and co-create with them?

- Productive partnership is impossible without understanding their stories and traumas

- Understand the power dynamics

- Moving at the speed of trust is slow

The healthcare profession has systemically mistreated the Black community, which has resulted in longstanding mistrust. This research project aims to understand this experience and the results published in “Building Trust: Black Experiences in Healthcare”. Some of the key takeaways include:

- The first point in learning is to understand the mistrust that has been done

- Understand the one-on-one relationship between doctor and patient. What is the trust relationship?

- Results from Gensler’s Outpatient Healthcare Experience Index indicate Black and LatinX respondents reporting the lowest trust

- Via open and honest conversations to understand the barriers of trust in healthcare how can we improve the healthcare experience?

City Pulse Survey Spring 2022 addresses concerns regarding what futures our cities hold

Image Credit: Gensler

Mental Health & The Battle to Find Ourselves

In this session Dan Lester, Director of Field Diversity, Inclusion & Culture at Clayco, opened the conversation toward how we can create a psychologically safe work environment and support mental wellness. Mental health can be characterized as a state of mind. It includes emotional well-being, good behavioral adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands of life. In our industry (architecture, construction and engineering) 83% of people experience a mental health challenge. Alarmingly this feels like a high number, but what this can tell us is that we may all be struggling with something and need each other’s support. Mental health challenges transcend race and cultural barriers. Acknowledging this fact could allow us to begin to foster more supportive environments around one another. One way to do this is to create a sense of “Psychological Safety”. This is a shared feeling that it is ok to be open and honest in a group setting without fear and retaliation. What are the steps that this could be achieved?

- Make it an explicit priority

- Facilitate everyone speaking up

- Establish norms for how failure is handles

- Create space for new ideas (even wild ones)

- Embrace productive conflict

Why is creating a sense of psychological safety in the workplace important? It opens up the potential for people with and without mental health challenges to share ideas without losing their jobs. Essentially removing the stigma barrier and allowing for creative idea sharing. By acknowledging our common humanity, respecting others, and we can then work toward the pursuit of making meaningful, creative contributions.

Conclusion

The panel series provided a wealth of knowledge that can help inform our design thinking in terms of equity-centered design practices. In addition, outside of the lectures, discussions, and panel series there was still time to cherish the opportunity to reconnect with old friends, spontaneous introductions toward new friendships and genuine network building. This reconnection provided exciting opportunities to engage with and be energized by fellow peers. Community and unity is a large part of NOMA’s initiative. NOMA’s strength is built through unity, and this could be fully felt when we were welcomed into the “NOMA-Nash family,” an extension of a much larger community. We are thankful to have had this opportunity not only to learn about topics such as EDI in architecture, community engagement in design and equity-centered research in practice, but to unplug and reconnect with our peers.

Resources

RCC_PlaceDrivingEquity.pdf (civiccommons.us)

Nashville/Davidson Metro Criminal Justice Center and SPMI Unit – AIA

Davidson County Criminal Justice Center – HOK

Reflecting on the First Year of Black Lives and Design Grants – Gensler