Last week Kieran Martin and Alison Duncan both attended the Toyo Ito lecture, “Limitations of Modernism,” at MIT. Toyo Ito received the 2013 Pritzker Architecture Prize. Here, Kieran and Alison have shared their impressions of Ito’s discussion.

Kieran Martin

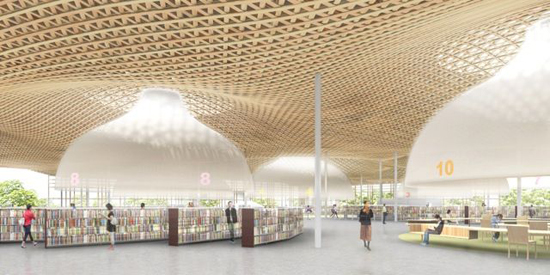

It was an incredible experience to watch Toyo Ito’s lecture in a hall designed by Eero Saarinen, two architects who I feel have pushed the structural and formal limits of their time. What was particularly engaging about Mr. Ito’s lecture was the premise that we, as humans, are more at home in buildings that present organic forms as opposed to the normative forms of modernism. Even though he viewed his early modernist work as “beautiful,” he departed from this aesthetic in search of a more comfortable environment influenced by nature. Through structural innovation, the architect has been able to harness mathematical and mimetic design to develop spaces which cooperate with the load bearing elements of his buildings. In this way Mr. Ito has been able to create seminal works such as Sendai Mediatheque, Tod’s Tokyo and the currently under construction Taichung Metropolitan Opera. If there is a criticism of his work it would be the seeming disconnect between structural form finding and building programming. While the structural innovations often provided stunning architectural opportunities, his process led me to believe that these opportunities were only considered after the form was in place. With this being said, I found his lecture to be very honest and powerfully understated for a man who just accepted our industry’s highest honor the previous evening.

Alison Duncan

Like many architects with a strong conceptual basis for his cutting edge architecture, Toyo Ito has defined his concepts in a very particular way that allows him to explore a variety of ways of form- and space-making all under the umbrella of a single concept. In the case of Ito’s recent lecture at MIT, “Limitations of Modernism Architecture,” the main limitation that Mr. Ito defined was a separation that architecture of the 20th century created between the people inhabiting buildings and nature. What was most interesting to me was how he then defined what creating connections between nature and people in each of the projects he presented. Mr. Ito recognized the difficulty in connecting people to nature through buildings which are inherently physically and culturally constructed as separate from nature. During the Q&A session he even went as far to say that the goal of his architecture is to not have architecture, which is how close Mr. Ito wants to connect us to nature. How this connection to nature works has varied quite a bit over the course of Mr. Ito’s work depending on where each project he presented fell in his career and the constraints of the site, program and client. His most extreme, and perhaps most convincing, design to connect people to nature was the house he designed for himself and his family near the beginning of his career. The Silver Hut is a series of lightly constructed pavilions connected by a partially covered courtyard that creates the most minimal of barriers between the inhabitants and the conditions of nature around them (even to the point where his family complained of having to carry umbrellas with them in the house). As his career has progressed and Toyo Ito’s projects have moved to larger programs and more urban sites, the challenges of connecting people to nature seems to have grown significantly, to the point that the compromises that are required of this overarching concept push it into territory that some may consider too far from nature. In looking at the Tod’s building in Omotesando, for example, it seems that Mr. Ito was limited in his connections to nature so much that it was reduced to an abstracted tree form to create structure and façade. His projects that were actually situated in a natural landscape, like the funeral home in Kakamigahara, were much more convincing to me as they connected the inhabitants to nature on multiple levels through formal, spatial and experiential means. I did think it was refreshing that Mr. Ito accepted the formal approach to incorporating nature into this designs that other architects might reject as being too limited an interpretation of nature. When this formal approach supplements spatial and functional elements of nature is when Toyo Ito’s architecture gets much closer to meeting his goal.

Cover Image: The Taichung Metropolitan Opera House is built by the Taichung City Government, Republic of China (Taiwan)

Image Source: MIT ARCHITECTURE