Web traffic diagram. Credit: James Spahr via visualcomplexity.com

Architectural conception is often thought of as a singular idea of an experienced master, a kind of creative black box within the head of a great designer. The emergence of a diagrammatic design process has challenged that notion, and allowed outsiders a view into architecture’s means of creation. Recently, the role of the architectural diagram has blossomed into more than a tool to present diverse information, but the beacon for a new architectural methodology. The work of UN Studio, OMA and Peter Eisenman all show that the process of visual analysis can help embed a multiplicity of understanding into each object or system of design. Through its recent evolution the diagram has been criticized for being inhuman, reductive, degrading and sterile, but for all this negativity I argue that the diagram is a powerful tool in the exploration, understanding and dissemination of an architectural idea.

The architectural diagram is an abstraction of all available information that allows the designer to focus dialogue on specific aspects of the design problem. In this way all architectural drawings are diagrammatic as they, through traditional abstractions, collapse three dimensions into two. Plans, elevations and sections are classic examples of what I will call representational (or building) diagrams, those that allow outsiders access to inherent, underlying concepts. Another type of diagram that can be useful in the design process is the generative (or design) diagram, which can act as an instrument of translation between intent and object. According to Gilles Deleuze, the generative diagram is a map of otherwise invisible flows, forces, relations and intensities at any given place and time. The generative diagram can act not only as a display of the architect’s deep understanding of the problem, but can also focus the design effort on otherwise unseen factors.

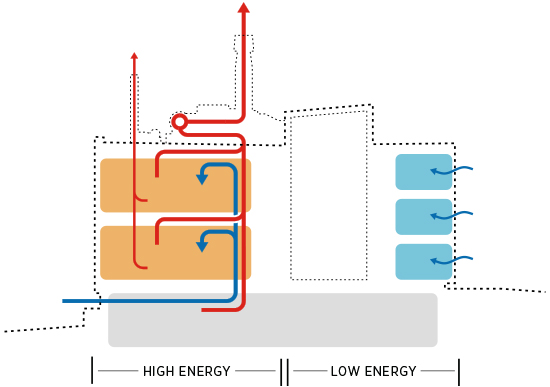

In my experience we use a plethora of diagramming to convey specific information to our clients, about their current space, energy use and efficiency. These are typically representational diagrams that directly reference physical conditions and accessible data. While generally produced to invite the client into PAYETTE’s thought process, they are also useful for consolidating the team’s understanding of the current conditions and possible courses of action. At the same time there are opportunities to dive deeper into our understanding of the situation through generative diagrams that reference less accessible information and leverage an experiential understanding of the conditions. This diagram can be as simple as an analogous biological situation or as complex as an intensity map in four dimensions.

PAYETTE’s Comer Lab is one project that clearly benefits from a generative diagrammatic process. In viewing the transverse section, it is clear that an abstract understanding of intensity of use, physical flows and temporal relations have been embedded into the project through the act of diagramming. I recently visited Comer and was impressed by the way the labs and offices activate each other while maintaining an ease of movement throughout the building, even on a busy weekday. While I do not feel that we need to read the diagram in each completed project, it is an impressive feat to understand the process of conception in a successful building.