Where do greenhouses originate from? In service to their emperor, Tiberius, the gardeners of ancient Rome used environmentally-controlled methods of carting vegetables out during the winter days in sunlight and bringing them in at night to ensure that the Emperor would be able to eat his favorite cucumber-like delicacy every day, year-round. Little did the emperor’s gardeners know that they would be inventing agricultural and botanical proto-greenhouses that would persist into modern civilization. Commercial greenhouses today are often designed with the intent of maximizing a crop’s output potential, or are places where specific plants can be grown in a controlled environment with the ability for year-round production, and therefore, year-round consumption. Where else would tomatoes and long-stem roses come from in the middle of a cold and wintery February? But greenhouses for research differ quite substantially.

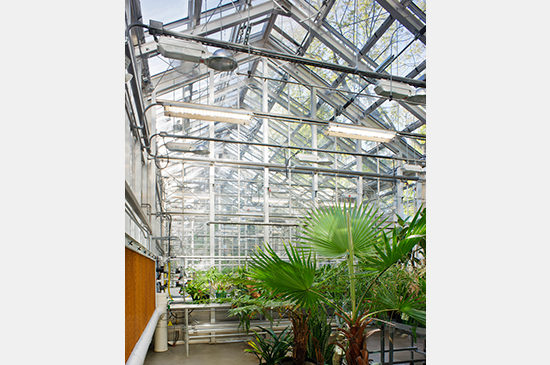

Academic and cultural institutions are increasingly incorporating greenhouses as part of their community outreach, or as a significant component to their scientific research facilities and research initiatives. Greenhouses are homes for very meaningful research, preservation and education. They are being used not only for botanical education and demonstration, but for the simulation of distinct climate zones and environments which can aid in the preservation of rare plant or animal species, or for producing transgenic plant material or microbes to be used in leading research experiments. They are also used in testing the impact or effect of certain pathogens on crops to help understand a plant’s resistance to prevent pandemic crop disease, or in examining the impact of pesticides and fungicides in an effort to reverse the decline of the honey bee population (see Colony Collapse Disorder). Greenhouses are becoming increasingly integral necessities to these scientific research communities and less affiliated with just purely crop production, but rather as essential contributors to developing scientific solutions to urgent problems we face.

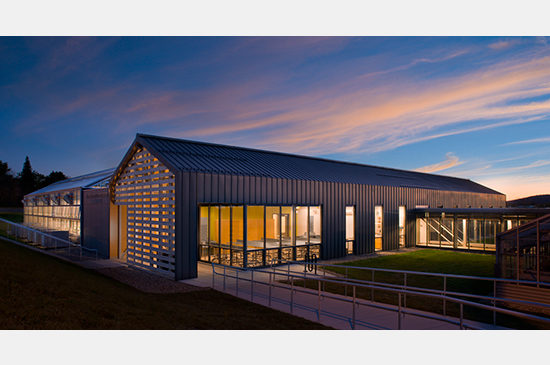

Many academic greenhouses are standalone facilities or complexes affiliated with certain academic programs, such as the CNS Research & Education Greenhouse at University of Massachusetts, Amherst and the greenhouse at the Science and Mathematics Center for Bridgewater State University’s Biology program. Where site constraints pose a challenge, or where a greenhouse at grade is not desired, greenhouses may also be integrated within the footprint of a building, such as at the Pennsylvania State University Life Sciences Building.

Often times, the programming, design and construction of greenhouses can be extremely complex due to the need to support plant growth in a controlled environment while the exterior environment is always changing: 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Not to mention they can have very intensive energy requirements, and many automated components including shading and watering for self-operation. Some greenhouses associated with research also have special cross-contamination prevention protocols or containment requirements.

Resources:

Practical Guide to Containment (Greenhouse Research)

Wikipedia – Greenhouse History

What the Roman Emperor Tiberius Grew in his Greenhouses