Designing for healthcare in an international context can add a layer of challenge onto an already complex design process. Healthcare architects endeavor to design buildings that strive to address multiple goals:

- create comforting, healing environments for patients, family and staff

- constructed on budget and responds to the architectural goals of the client

- use as little energy as possible while providing redundancy and resiliency of systems

What happens when the context in which you work has a different set of assumptions about culture, operations, infrastructure and climate – i.e. an international context?

An architect can transform complex design challenges into opportunities that create environments for healing that serve patients, family and staff, regardless of a building’s location. Some of these opportunities are only possible to implement on international projects and can be leveraged to advance healthcare design further than is currently possible in the more closely regulated U.S. market.

I’ve worked on international healthcare projects in different regions over the past five years and I’ve recently joined the AIA’s International Practice Committee Advisory Group. Both experiences have led to conversations and in-depth thinking about the unique opportunities and challenges present when combining global practice with the healthcare design market. The challenges range from people-centered questions of operations and culture, to architectural questions of materials and context, and technical questions about resiliency, sustainability and the availability of infrastructure. In a series of posts, I’ll share my thoughts regarding the opportunities healthcare architects can leverage within all these challenges when practicing internationally.

Cultural Context

How many people accompany you when you check into the hospital? What time of day do you visit hospitalized family members? How long is your visit? When you go to an outpatient center for a check-up do you make an appointment ahead of time and arrive with full confidence that you will see a healthcare provider the same day? If you are admitted to the hospital for an extended stay do you assume that the hospital will provide food and laundry services for you? For your family? How frequently do you worry about your privacy when you are seeing a healthcare professional?

All of the above questions are ones that healthcare designers consider, regardless of a building’s geographical location. However, the answers to these questions might differ significantly in an international context. Understanding the implications of cultural norms, the relationships between patients and staff, how healthcare is delivered, and the expectations for healing environments is one of the greatest challenges for healthcare architects who are working on projects outside of our own culture and context.

Patients, family and staff experience unusually stressful situations, both positive and negative in nature, while in healthcare environments: birth, death, diagnosis of illness and news of recovery, to name a few. The cultural patterns and rituals associated with these times of crisis vary significantly between cultures and impact how healthcare environments need to accommodate them. Sometimes the impacts of these cultural differences are clear, while other times they are more subtle.

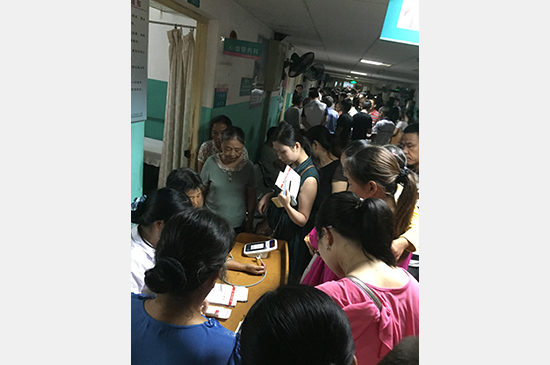

As one example, for some of the international contexts where I’m designing, from Pakistan and East Africa to China, the cultural norm is for patients to bring many people with them to the hospital and those people remain with the patient for the duration of their stay. The reason behind this pattern can vary depending on the particular context. In more rural contexts patients may bring their entire family to the hospital because they must travel long distances to receive care. In other contexts, healthcare providers expect that patients will arrive with family members who will take care of certain elements of patient care: providing food for patients, laundering clothing and linens during the patient’s stay, and even performing tasks that in the U.S. would be the sole purview of healthcare professionals, like medication administration. In more affluent contexts, patients may arrive with staff who they view as essential for the continuation of their livelihood despite their need for medical attention.

For healthcare architects the challenge is to accommodate the volume and needs of the additional people accompanying patients who are sometimes integrated in the patient care delivery model. Often this design challenge is complicated by the fact that the hospitals we design in international contexts must use multi-patient inpatient room models in order to provide the needed care to their populations and remain financially viable. We cannot simply rely on private patient rooms to accommodate all the needs of patients and their families. Instead, we must consider a range of spaces and amenities in a hospital complex to meet the needs of all users.

We as designers need to leverage the opportunities inherent in spaces we already provide in healthcare environments that will support the needs of extended families. Public and exterior spaces can be activated by amenities that are specifically targeted to families. Healing gardens and courtyards that provide daylighting and other environmental comfort benefits can be leveraged for flexible family waiting spaces. Multiple scales of spaces located on inpatient units that can be used by families while patients receive care should be considered opportunities for education and the creation of support networks. Of course, whenever possible, it is essential to design patient rooms to provide space to welcome families into this environment, even if only in the form of enough space to sit and visit without interfering with staff work flow. Ultimately spaces that are focused on supporting families will also support patient healing.

Incorporating time for observation and user interviews into the design process on international projects becomes even more critical to uncover underlying assumptions about interactions between patients, families and staff. It is our role as designers to search for and unpack the assumptions that our clients and we make about what spaces are needed, how those spaces are used and by whom. Without this search for understanding of cultural assumptions we would not discover the design opportunities that result in places of healing and comfort no matter the context.

This Friday (5/20) I’ll continue this conversation at the AIA Convention alongside other architects who practice internationally. You can follow along using the hashtag #aiaintl or join us in our session (FR408).