In Part 1 of this series, I shared my thoughts on the importance of understanding the implications that culture has on healthcare design in international contexts. What is the impact of architectural and construction constraints on how we deliver healthcare projects in a global practice?

There are two contexts that need to be considered to successfully deliver healthcare architecture internationally:

– how to meet our client’s architectural vision from a design perspective

– how to deliver an international standard healthcare building on budget and on time in contexts with constrained resources and construction methods

Architectural Context

Hospitals are important elements of community infrastructure, and it is important that they are open and welcoming to patients and visitors. This is particularly true for hospitals in countries where healthcare is not readily available. Designing healthcare buildings that feel welcoming can also be challenging in cultural contexts where healthcare providers can sometimes be viewed with mistrust. How architecture manifests openness, authority, safety and health in a community depends on the vision of a particular client and how healthcare and architecture are viewed in a particular community. Just like we, as healthcare designers in an international context, must probe and question our own assumptions about how cultural norms impact the needs of the users of our buildings, we must also investigate the role that architecture plays in meeting our client’s vision and the role of our design in the community.

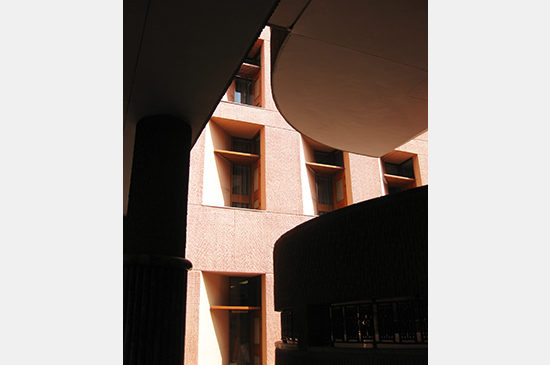

The Aga Khan University Hospital campus in Karachi, Pakistan is an example of architectural expression and campus design that was developed in response to unique needs of an international client with a vision both for healthcare delivery in the developing world and a modern, yet culturally responsive architectural expression. The original design team for the hospital and medical school campus in Karachi, had the advantage of an immersive tour of architecture of the Islamic world to study and understand the cultural underpinnings of spaces designed across regions and generations. Organized around a series of interconnected courtyards on a landscaped campus, the AKU Hospital and Faculty of Health Sciences translates culturally familiar courtyard and portal building typologies into a modern architectural idiom. The cultural comfort with courtyard and building form, integration of soothing and healing landscape, and protectiveness of a secure campus have all contributed to an active and successful hospital environment. Providing spaces that feel safe to the local community aligned with the client’s desire to encourage medical education and international standard healthcare delivery in a place where both are less commonly available and security is a high priority.

Not all design teams have the benefit of the time to study the architectural history of a culture in-depth. However, we can apply tenets of good design to different cultural contexts successfully by understanding which of our design goals transcend cultural differences and specific contexts. In healthcare design, myriad studies* have shown the positive impacts that proximity to nature has on patient healing and reduction of stress for families and staff. When designing the Fifth XiangYa Hospital in Changsha, China, our vision focused on the larger community’s access to a park adjacent to the hospital site and directed views from the patient rooms toward both the park and a central healing garden. We combined this focus on integration of landscape and nature, an architectural value that we apply to all of our designs, with the specifics of the site and knowledge we gained from our local architect’s team about patient room orientation and relationship to feng shui. Layering ideas about integration of nature into hospital design, flexibility in circulation and patient unit organization, and local cultural needs related to views and orientation combined in a building organization and massing that responded to multiple parts of the clients’ vision and users and community needs.

Construction Context

It is one thing to design architecture that responds to a specific international context, and another challenge to construct that building. Local partners in international practice are essential to understanding how availability of materials and construction methods will impact architectural design decisions. The earlier in the design process the constraints of the local construction market can be understood in design, the more easily that understanding can be leveraged to make good, holistic design decisions.

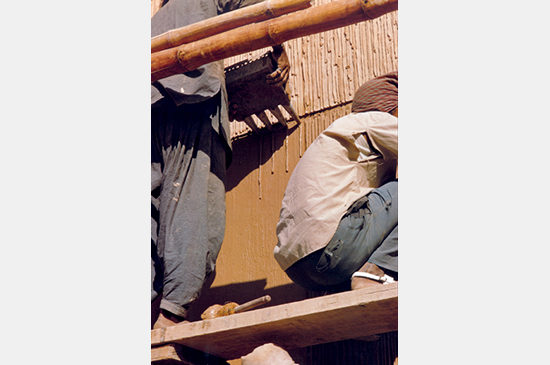

Many countries in which we design international healthcare buildings are more resource constrained than the U.S. Relying on local techniques and construction materials offers opportunities for both more economic construction and more sustainable, resilient design. Perhaps unique to healthcare design, using local materials for building construction can also balance construction budgets that need to accommodate essential medical and building equipment that likely need to be imported. Local construction methods are often more responsive to local climatic conditions, such as the weeping plaster applied to the Aga Khan University Hospital that shelf-shades the façade and reduces glare in the sunny Karachi climate. Designing with local materials also engages local craftspeople which can offer the added benefits of easing long-term maintenance and supporting the local economy. Each of these benefits often coincide with the goals of hospitals and healthcare buildings serving as anchors for larger communities.

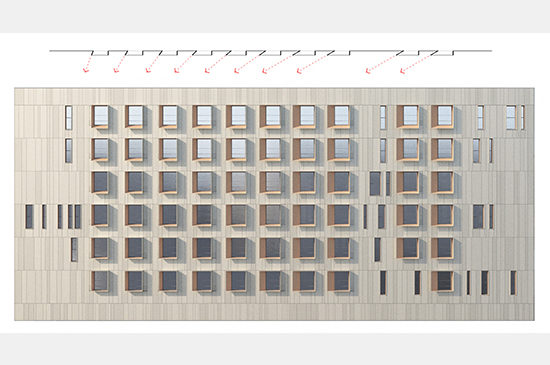

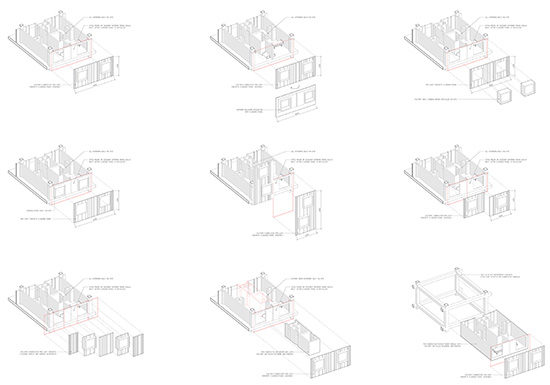

In China, where resources are less constrained, understanding construction methods can be just as important to successfully deliver international standard healthcare architecture. When designing a hospital that is 5 million SM in area with 2,500 patient beds, there are inevitably design elements that repeat on a huge scale. When we conceived the family nest concept for the Fifth XiangYa Hospital, our team was not only excited about the design implications of incorporating a human scaled element into an immense façade, but also the potential to prefabricate modules, potentially even patient rooms, design decisions which directly address questions of schedule and cost. Through conversations with our local partners however, we discovered that pre-fabrication was not a typical construction method in Changsha, particularly not on the scale we envisioned. Instead, the more economical approach was to panelize parts of the façade and standardize those panels into a kit of parts that could be arranged to provide variety within the façade system. Learning this detail of local construction methods impacted further decisions about materials and façade details that were essential to understand early in design.

Many of the architectural and construction design challenges associated with complex healthcare buildings are the same regardless of the project’s location. The added complexity of an international context for designers is to understand the assumptions we make about how to achieve our client’s vision through architecture; address larger needs of site, community, and access; and understand local methods of construction and availability of materials to ensure our designs are achievable.

* Examples of relevant studies:

Role of the Physical Environment in the Hospital of the 21st Century

Dying in the dark: sunshine, gender and outcomes in myocardial infarction