As architects and designers, we produce lots of graphic content. We begin each project by courting potential clients with our vision, presented via renderings or artful hand-drawn sketches. We then march onwards, producing drawings and diagrams with the aid of rendering programs and our drawing software of choice. Finally, during the construction phase, we mark-up shop drawings and produce bulletins and sketches, which communicate the design intent to both our client and contractor in a way that mere words cannot. The entire design and construction process hinges on us being able to communicate our ideas with the outside world via visual content.

Of course, we also communicate with our peers and fellow design professionals via graphic tools as well. This content is often hand-drawn and pinned-up during critiques or meetings as topics of discussion and as aids in decision making. We are accustomed to communicating with each other in this graphic language. Often, we curate these sketches, knowing that they will be judged by our peers, and as a result, we strive to create poignant, clear and beautiful sketches that simultaneously inform and impress.

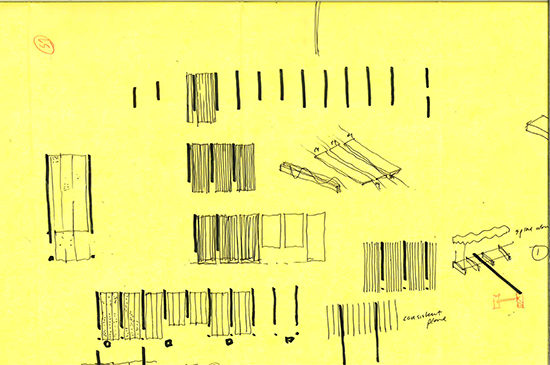

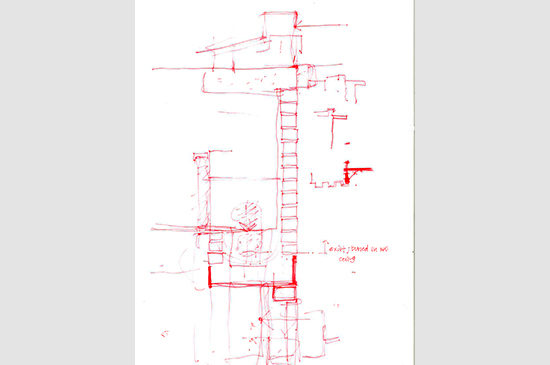

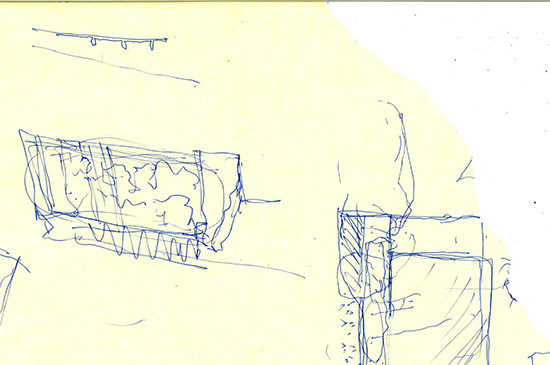

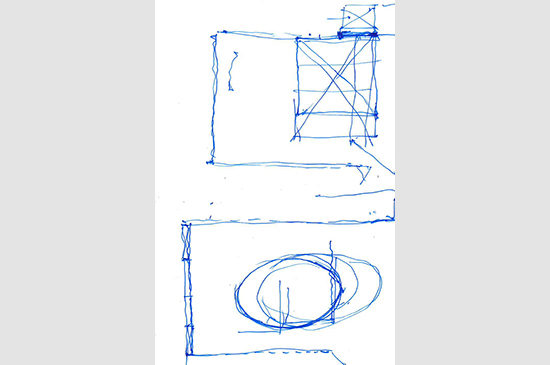

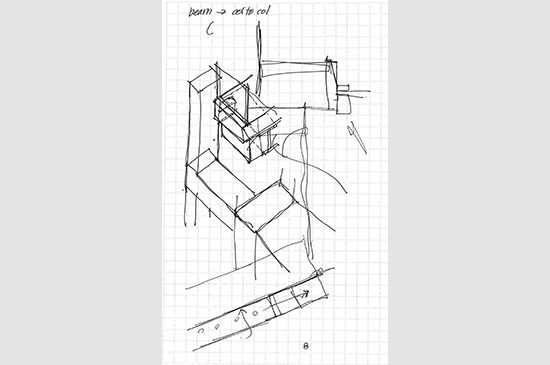

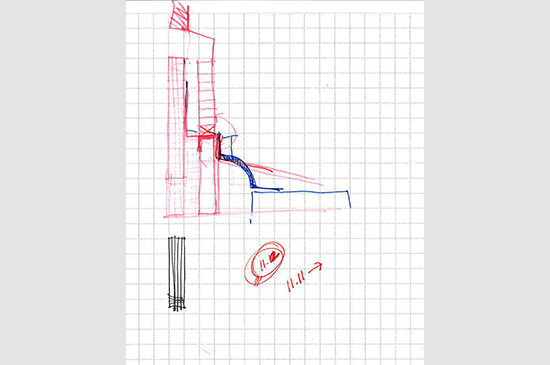

But there is another form of this graphic language that we utilize in the individual realm that exists solely between our brain and our hands. More than a language, it is a skill which we draw upon to decode, to demystify, to understand. This language is messy and rough – perhaps akin to the slang that one may use at home amidst family and friends, but never among colleagues or clients. This is the graphic language of ‘figuring it out’.

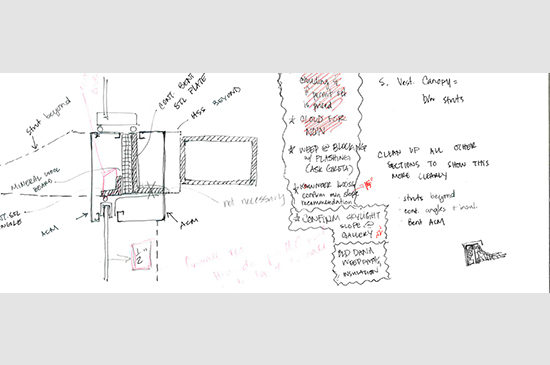

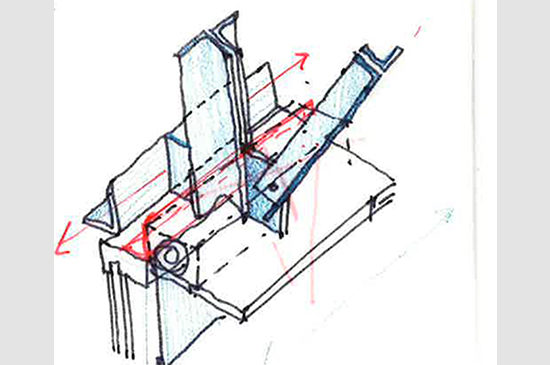

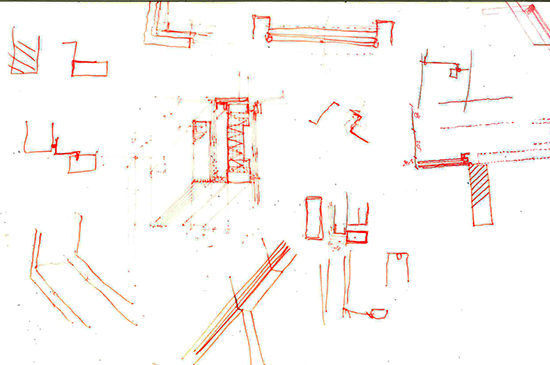

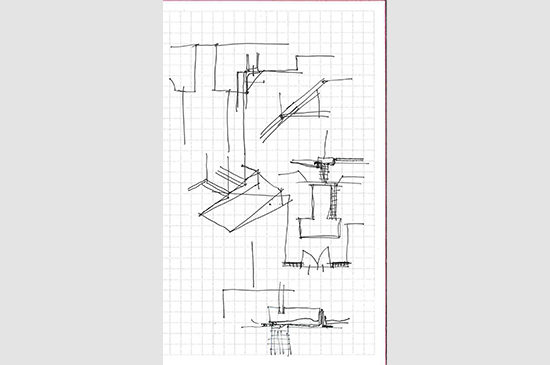

Walk around our office, and you will find desks littered with scraps of paper that show evidence of this type of problem solving. However, this evidence often does not last long, and rarely is it ever saved, displayed or archived in any fashion. I’ve seen these sketches fill trash bins during desk moves or at the end of project deadlines when we are trying to mentally and physically regroup. And while their time on this earth is fleeting, before they are dumped in the recycling bin, their purpose is critical. These sketches highlight how we think as designers in a way that is often not shared with the outside world or even each other.

When I asked a few of my peers to pull out any sketches they had that captured the spirit of ‘figuring it out’, they often handed me stunning hand-drawn plans or diagrams of details with perfectly diagonal hatch patterns and artful hand-lettered call-outs. While these were beautiful, and certainly captured the way we communicate with our peers, they did not capture the no-nonsense style of one who is drawing simply for his or her eyes and mind only without graphic beauty in mind, in a quest to gain understanding.

With a little nosing, I was usually able to find these messy gems sitting on top of file cabinets, piled in a forgotten corner of a desk or even poking out of the trash bin. “What, these?” they would ask when I pointed. Not to the artful napkin sketches displayed, but the sloppier scribblings scrawled on a beat-up piece of trace. “Yes, those.” I would reply. “What were you trying to understand when you drew this?”

Many times people did not remember. They’d peer at the drawing in question, as if trying to look back through time. “I have no idea,” one person commented.

For me, this is the perfect response. The sketch is evidence of a small slice in time, of the rumination of a problem, even if it was not solved. Not every decision made or problem solved is the result of some massive brainstorming session involving fancy graphics and presentation aids. They are critical, then forgotten, allowing us to proceed to the next design task at hand.