The octopus has nine brains.

I began with the premise of writing about my experiences working on Drexel University’s Edmund D. Bossone Research Enterprise Center third floor renovation; but I can’t help but come back to an experience I had when I first joined PAYETTE earlier this year.

Which brings me back to the octopus.

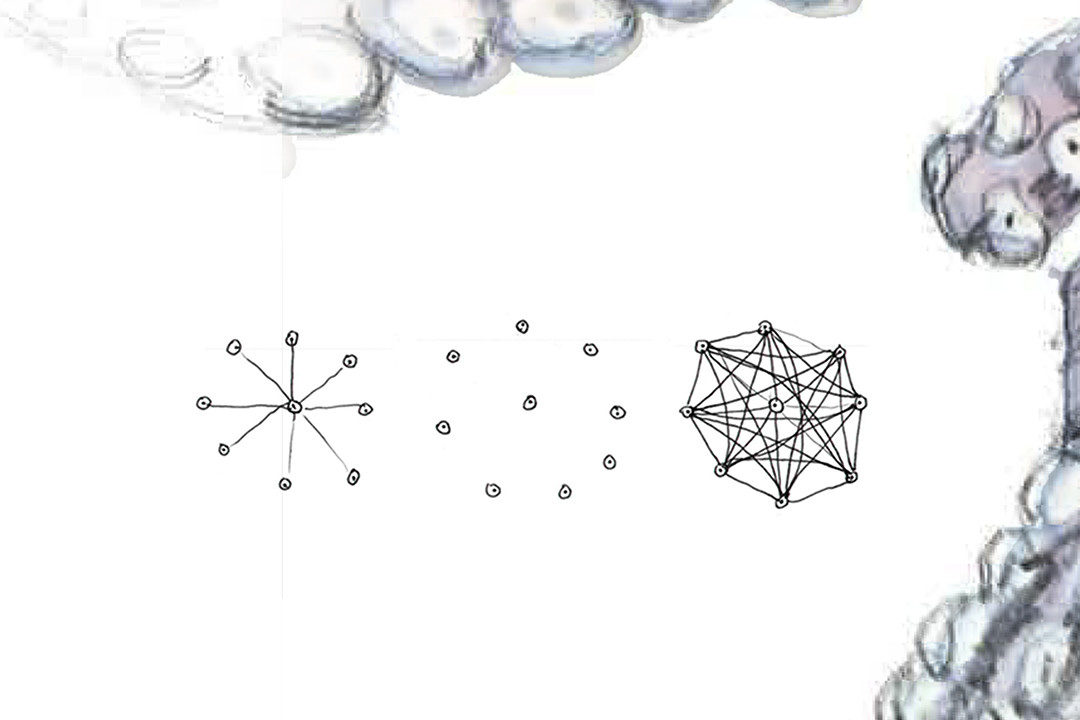

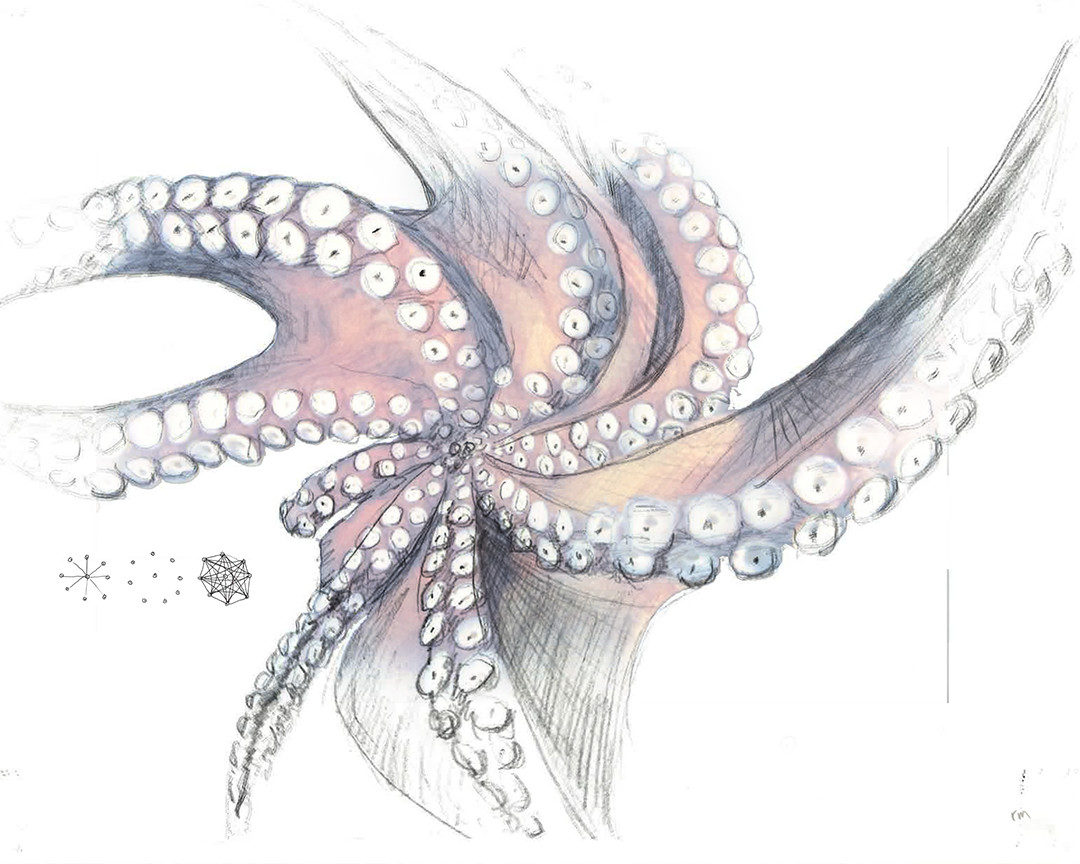

Without getting into the [sea]weeds of how their complex nervous systems function1 or concepts of haptic perception, exteroception and the likes − suffice it to say, I raise the topic because I’ve been thinking about perception2. A neural system not subservient to a central command suggests a way of processing and understanding information that is completely alien to how human minds perceive the world. Imagine what it is like for an octopus to experience a space − something processed as local perceptions rather than top-down or centralized conglomerations of inputs.

A seemingly separate, but at the same time, familiar perception.

When I first joined the firm, I was immediately immersed in the two-dimensional drawing of a site plan for a feasibility study. My first few weeks were spent learning and seeing the college through lines drawn at 1/32” = 1’-0” and in more specific focus at 1/64” = 1’-0”.

And then I visited the campus.

It was a visit to meet with the researchers and review the current progress of the study, but as we approached campus this surreal feeling overcame me. I knew what I would see around the corner in a place I’d never visited before.

Like the arm of an octopus interdependently experiencing, exploring and perceiving an environment, I’d drawn myself into a sense of place. And now visiting the place, at the disposal of all five of my senses, not just the optical, I found quite striking.

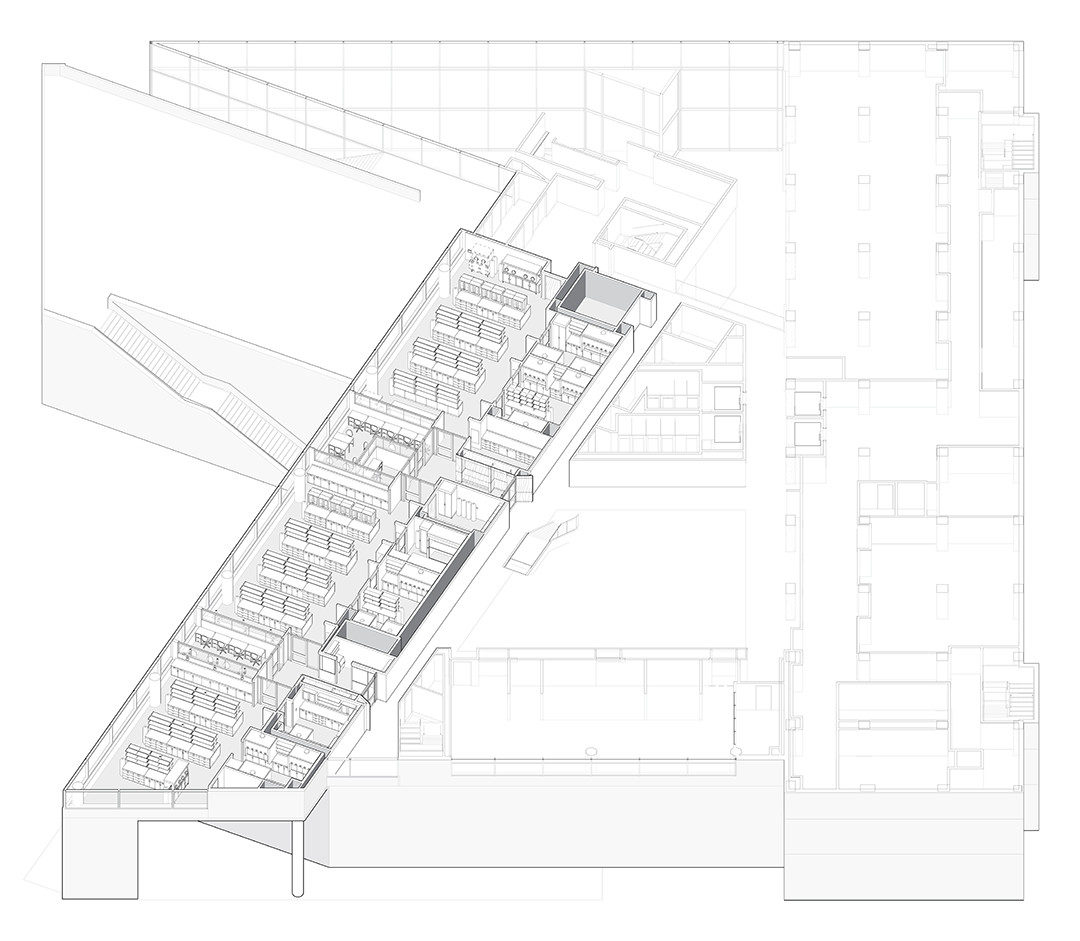

Which brings me to my work on our project at Drexel. Again, my introduction to the project was through drawing, though this time with a heavier dose of the three-dimensional realm of modeling. And again after weeks of getting to know a place through the tools of projection, I visited the site.

With the first encounter, my experience was at the scale of a campus, a street, a network of buildings; but the scope of work at Drexel is that of the scale of a building, a single floor, a network of labs. I found myself knowing what was around the corner, but this time, more intimately, a door leading to a stair I’ve never climbed.

As architects we draw ourselves into places we may never inhabit, into places that may never materialize. There is always some notion of distance in our work, distance between us and a drawing; distance between a drawing and a building; distance between where the work is conceived and where the work is sited. We are constantly working to create place whilst operating in displacement.

Much like the arm of an octopus can know the corner of a maze without the navigation of its central brain, we can know a space without having experienced it.

But it begs the question, what is left to the gaps of perception?

1 I should say more accurately, a large network of neurons, located for the most part in each of the eight limbs and the rest in what we could call a “central brain;” as it is not clear where the “brain” begins or ends in an octopus.

2 And, I’ve been reading a lot about octopuses lately.