Gerhard van der Linde recently joined the firm’s ranks of registered architects. Today we celebrate his accomplishments.

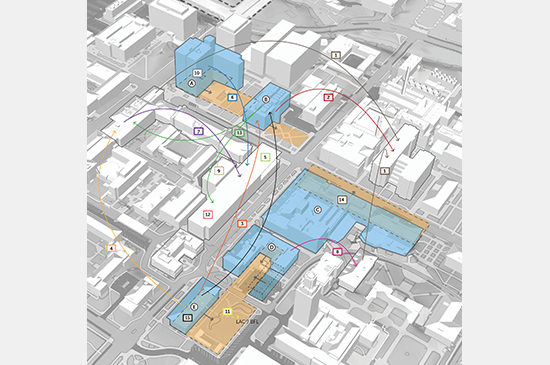

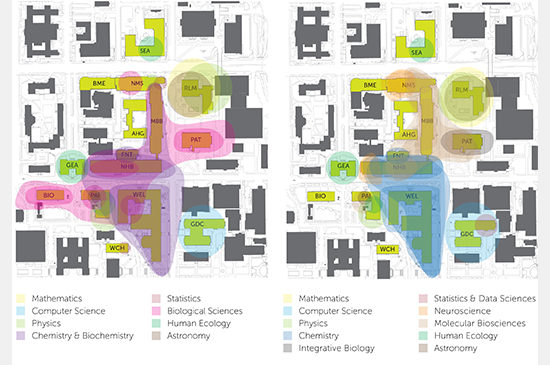

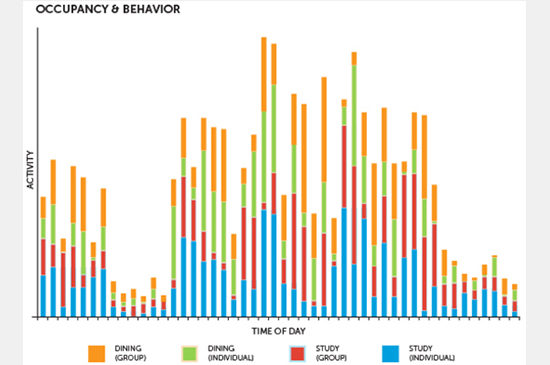

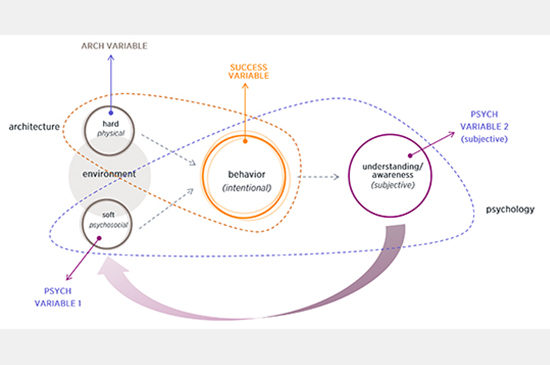

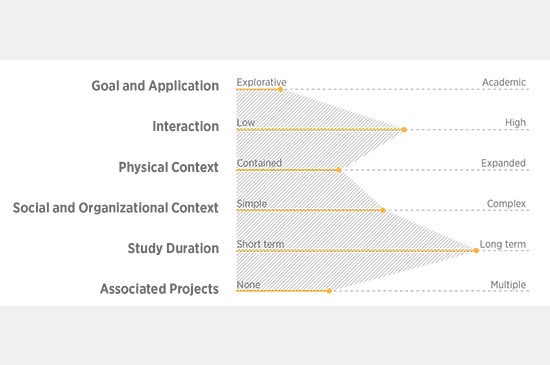

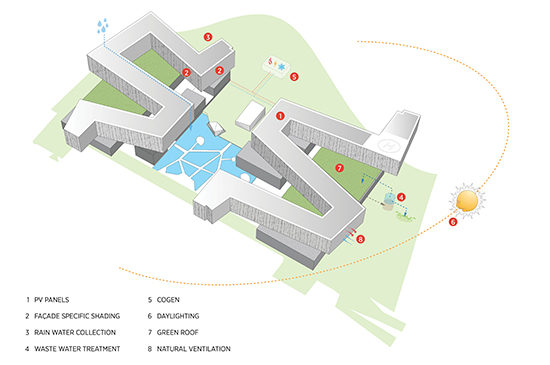

Gerhard joined PAYETTE as a designer in the spring of 2013. He has worked on the University of Texas at Austin College of Natural Sciences Master Space Plan and the Visioning Study for the School of Public Health at the University of Washington in Seattle. He is currently involved with the PSD, IME and CI Strategic Planning Study at University of Chicago, the UT Austin College of Liberal Arts Master Space Plan and an in-house research project on collaboration spaces.

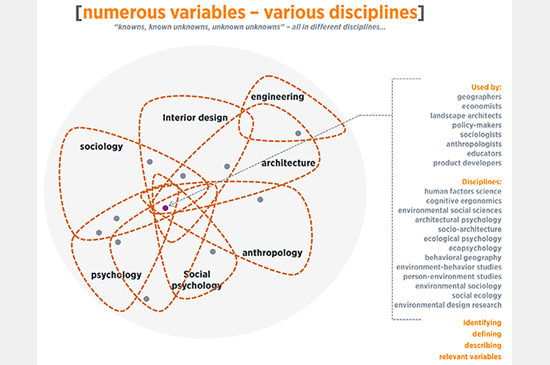

Gerhard received a Master of Social Sciences degree in Psychology from the University of the Free State in 2005 and a Master of Architecture degree from MIT in 2010. He is a member of the AIA and an Associate member of the American Psychological Association. Currently, he is developing the curriculum for the Environment and Behavior studio-lab to be presented as part of the Design for Human Health program at the Boston Architectural College.

What inspires you?

The thought of all the things—big and small— that remain unknown to me inspires, and constrains me.

What is the best part of your job?

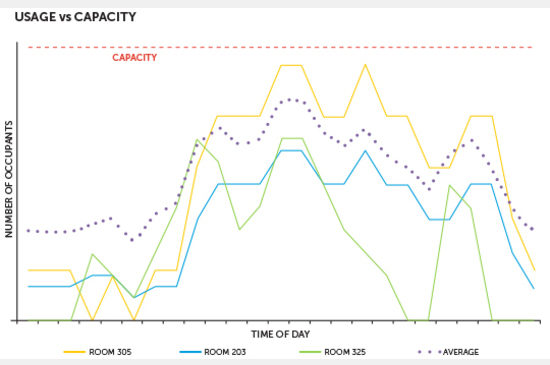

After wrestling with a mass of tangled and seemingly unrelated data, with the involvement and insight of many other incredibly talented colleagues, to see patterns and trends surface that enable us to help clients plot a course for the future.

What is the most important thing you’ve learned so far?

That all aspects of design, whether it is sketching through a problem, or analyzing data that leads to the questions we need to ask, take time. When one rushes through these initial phases to get to the “real” work, it is easy to miss the unique opportunities a project offers. Similarly, I’ve learned not to judge an idea or solution based on its apparent simplicity.

The sky is the limit: if you could design or redesign anything, what would it be?

Views of what the future can—or should—be. As designers and architects, it is easy to default to the general agendas of our present time when thinking about the future. Architecture, however, is one of those rare fields where we have the opportunity to envision, albeit imperfectly, the future of our world with an optimistic realism. We need to acknowledge that, on the scale of world history, our individual impacts are miniscule, and ask ourselves: what is the vision of the future that guides my efforts? I think it is partly this conviction about the future that determines the impact, relevance, value and permanence of our work. Shaping this conviction is the most important, and most difficult, design project.