As architects, we use design as a tool to generate influence. “To design is to influence the experience of individuals, the fabric of communities, the structure of organizations, and the dynamics of systems.” We recently had the opportunity to explore the breadth of our influence by attending the sixth annual HarvardxDesign Conference: InfluencexDesign, held February 23-24.

Organized by a team of students from Harvard Business School and Harvard Graduate School of Design, the conference provides an opportunity for designers, entrepreneurs, activists, researchers, engineers, psychologists and professionals to participate in an exchange of ideas. While we were all influenced by the panel sessions in different ways, it was evident that regardless of scale designers and architects act as agents of change, impacting the human experience.

Design as a Collaborative Enterprise

Written By Hilary Barlow

Advancements in technology have made design increasingly collaborative — sole authorship seems to be a thing of the past. This notion of design as a collaborative endeavor and accessibility of participation was shared by the different panelists at each scale: individuals, communities, organizations and systems. Zachary McCune shared that Wikipedia imagines a world in which every single human being can freely share in the sum of all knowledge. Wikipedia depends on participation across cultures online; it’s only as good as people make it. Wikipedia is designed to be a shared process, unlike other panelists’ examples where collaboration is used to improve the end result. Kathleen Talbot of Reformation spoke of how much of the clothing company’s marketing and branding is shaped by social media feedback from consumers, such as through engagement in Instagram comments. The brand’s mission is to make sustainable clothing accessible to all and she noted that, “you can’t start a revolution if you don’t invite everyone.”

But does collaboration though social media, which encompasses instantaneous input and direct accessibility, begin to have a toxic impact on the architectural process? Architectural projects require a tremendous amount of collaboration and, once built, are much more difficult to change than a post or comment. Campaigns such as Wikipedia and Reformation are designed to be accessible to all through technological participation. Throughout an architectural project, a multitude of people participate and contribute to the design such as users, owners, the community at large, donors, consultants, contractors etc. While the process and product of architecture is a collective endeavor, there is a limit to the participation in its authorship. There comes a point in the design process where participation from non-architects must be limited in order for the design to advance and be built. As advancements in technology blur the line between authorship and participation, architects will have to navigate the changing role of collaboration and difficulty in planning for human behavior.

Design and Control

Written By Adam Wagner

Following the theme of influence, many speakers discussed the impact of their work as a study on human response to curated experiences. Their anecdotes, which shared overlapping topics like understanding consumer engagement, navigating social media, and shaping culture within a population, sought to interpret and apply just how and why our environment prompts certain behaviors from us. As architects we similarly study how bodies move through space and the effect of the built environment on the individual or community psyche. Although the self-appointed agency of architecture has not always been particularly modest (think: Architecture or Revolution¹), it is safe to say that architecture cannot be neutral as its impact stems from its tangibility. Our work as place-makers involves constant exploration of new strategies in planning, design, and construction, with the goal of improving the way we understand and occupy space. The question is what control do we have over the way in which it is ultimately used?

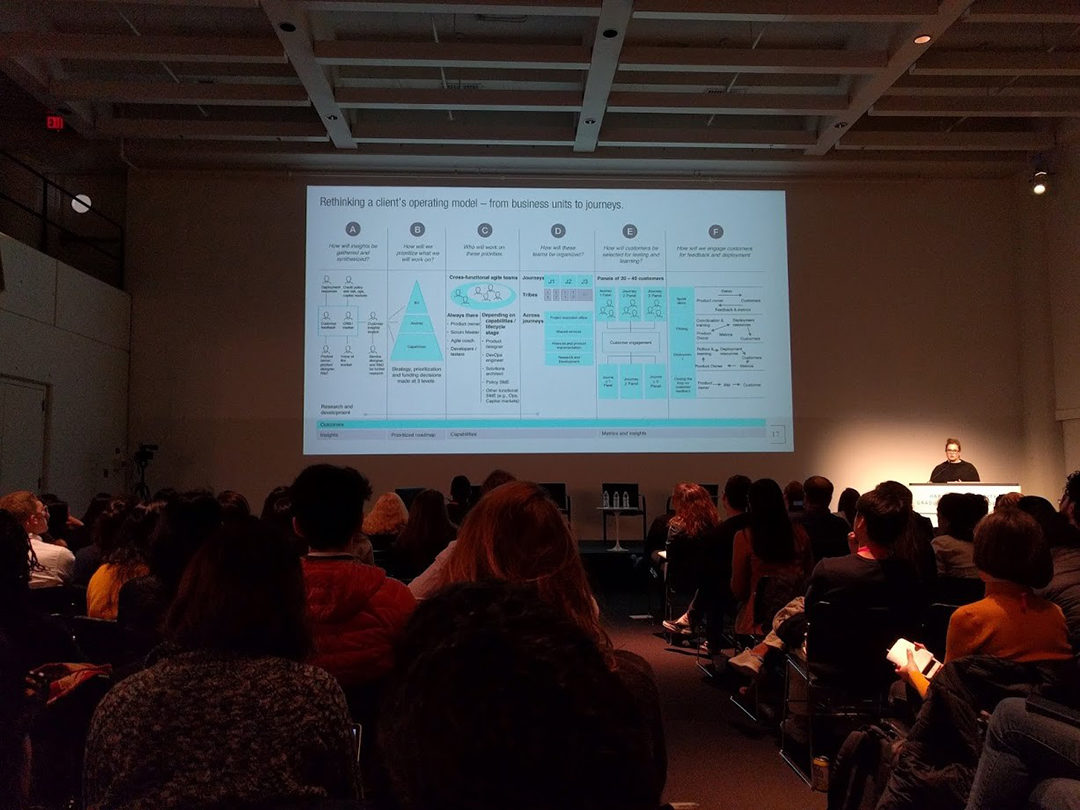

Joshua Emig, Head of Research and Development at WeWork, described the process of analyzing room usage data from their existing facilities for the planning and design of newer ones. He also recounted a study of their lesser-known WeLive spaces, which revealed that despite the variety and location of amenities provided to tenants, social networks that developed within each living community were limited by proximity and often fell apart when certain well-connected individuals moved away. These investigations highlight the ongoing cycle of feedback, in success or failure, between designed spaces and the reality of usage. As architects we share a collective database of experience, precedent knowledge that expands with each project and re-frames the way we conceptualizes various programs or spatial types to the benefit of future work; we learn, and that gives us control. If design generally is a marriage of precision and chance – an investigation calibrated by intent and accelerated by unexpected results – design control is the ability to steer that process methodically towards moments of discovery and subsequently to understand them and react accordingly. Unlike the fast-paced world around us or even the fascinating initiatives developed by many of the speakers, the project of Architecture is slow and heavy with permanence. Likewise, the role of the architect carries that weight too. The evolving nature of how humans inhabit space may seem to outpace design thinking, but architecture is the context from which it derives meaning. Our decisions carry impact and that compels us to do our best.

1 Le Corbusier uses this phrase as a central argument to his 1923 book Vers Une Architecture, commonly known in English as Towards a New Architecture. He declares that architecture must shift drastically to match advances in engineering and technology or face inevitable civil unrest. To conclude the introductory thesis of his writings, he writes the following:

The machinery of Society, profoundly out of gear, oscillates between an amelioration, of historical importance, and a catastrophe… the various classes of workers in society to-day no longer have dwellings adapted to their needs; neither the artisan nor the intellectual. It is a question of building which is at the root of the social unrest of to-day: architecture or revolution.

Designing between analog and digital

Written By Daniel Russoniello

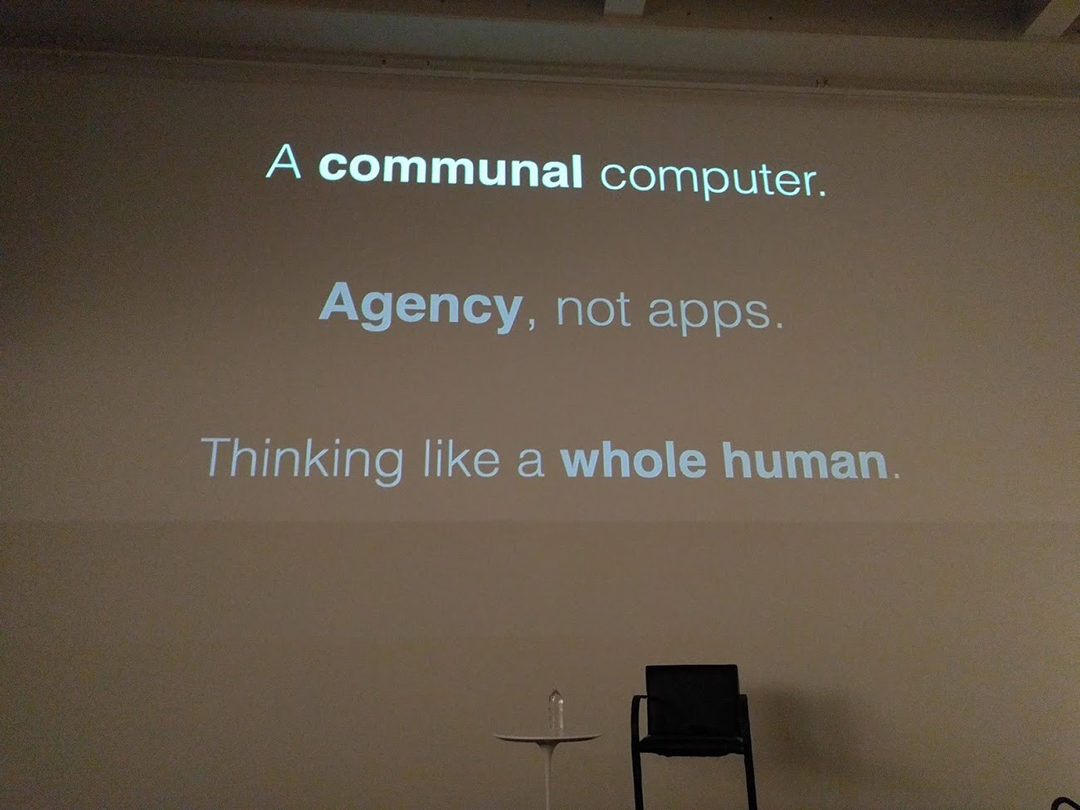

The closing keynote of the conference was delivered by Bret Victor who talked about his project Dynamicland. He began noting that “Computers were designed for an assumption of isolation” and proceeded to contrast analog crafts and activities that bring people together, with digital work and activities that have a tendency to isolate and constrain – making us behave as consumers rather than creators.

Dynamicland is a response to this: a format, or forum, for collective creation in a digitally enabled environment. Located in a ground floor space to be accessible to passersby, Dynamicland is designed to be usable even by those without knowledge of coding. The system consists of a large room in which people got together to collaborate to create tools and games. Users gather around the tables and manipulate pieces of paper with unique dot patterns at the corners. Projectors and cameras mounted above large tables read the objects, actions, taking place on the papers, and project graphics and information back onto specific pieces of paper. Each paper represents some lines of code that can be created or edited by the users; it is the combination of many of these sheets that create the ultimate tool or game. The system is run on computer hardware, but the users generate the code and sequences of actions that system takes, and the key here is that everyone around the table is involved simultaneously. All the pieces are laid out and display their function in real time, with the code for that function printed on that paper.

Breaking code down into small, tactile, interactive, real-time components, Dynamicland makes designing and using computer programs accessible, playful, and collaborative. This form of augmented reality has potential use in architectural design. A system of this type could be used to plan spaces with users in real time, and advanced virtual reality systems already offer multi-user functionality and the possibility of designing in the VR world. Dynamicland’s particular way of breaking things down into small components would enable a design team to rapidly iterate collaboratively, a process often undertaken individually, and then reviewed by a larger team. Lastly, its mix of paper-based, 3D and digital media maps the ways architects work: through hand sketching, physical modeling and computer generated graphics.