This essay first appeared in the program book accompanying “Beginnings: Drawing Early Architecture,” an exhibit on display at MIT. The exhibit is on display through August 15.

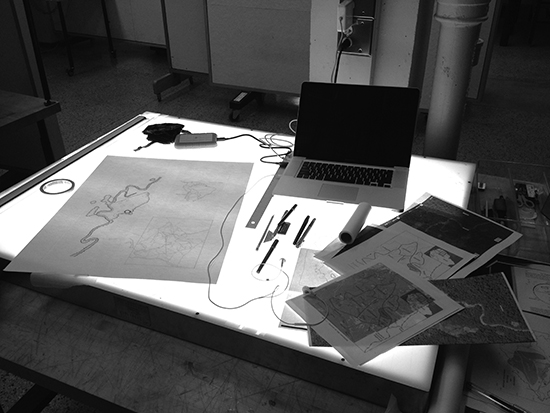

The glow of a light table—the kind used for drafting and art—is eerie. It throws light up onto the face and creates an unsettling glaring effect. We’re not used to light directed at us from below, and so these tabletop boxes can cause discomfort. And yet the glow of a light table is also compelling. It is the same light that shines up on John Travolta’s face when he opens up the mysterious suitcase in Pulp Fiction. It is the hot sunlight reflected from the surface of a swimming pool in summer. It is the unnatural radiance of a tanning bed. My fascination with the anomalous upward-shining beam of the light table arises mostly from its deceivingly simple function: in short, the ability to see through an opaque material—an x-ray machine without the harmful radiation. (In a strange inversion, light tables are also used to review x-ray slides. But for me, their real magic lies in seeing through opaque paper and tracing a normally hidden subject.)

When you use a light table to draw, the process involves the periodic turning on and off of the light source. The light needs to be on while actively tracing, but in many cases it is necessary to turn it off in order to properly see the progress of one’s handiwork. This type of switching back and forth is common in making art. It is what you do, for example, when sketching from life. The eye goes back and forth between the thing being sketched and the page. With the light table, you do the same thing, but instead of moving the eye from one thing to the other in space, you change the lighting to alter the visibility of the layered pieces of paper.

When the light is on, you don’t really see what you are producing, just the illuminated figure below. There is a muddy, fuzzy quality to the original. For even though the light table allows you to see the thing being traced, it remains an apparition interfering with your ability to perceive the new line you are creating above. And by concentrating on the original, you end up effectively ignoring your own marks. But once the light is switched off, the new figure jumps magically into being. The effect is similar to putting on glasses and seeing the world come instantly into focus.

In a certain way, your ignorance of your own creation allows you more freedom. Perception and production are decoupled: you don’t see what you’re making as you’re making it and you must wait for gratification until you’re ready to turn off the light and look back on your work.

These delays occur multiple times because using the tool is a cyclical endeavor, a process involving multiple steps that by turns obscure your work and reveal it. Generally, the tracing is done in pencil first, and then the drawing is inked without the use of the light table, after which you must erase the pencil work. Pencil is usually very light and thus hard to read. Inking brings definition, but the pencil lines that remain muddy the picture. It is only after erasing the pencil lines once the ink has dried that the final product can be judged.

The light table as used for copying a drawing by hand, or “tracing a drawing,” is rare in contemporary art and design. It is obvious why: we have not needed to copy by hand for over half a century. Analog and digital machines are so much better at it. But if you want to “improve” or “abstract” an existing image, rather than reproduce it 1:1, then the light table still has a place in the studio.

One benefit is that it allows one to steal something and make it one’s own without worrying over copyright infringement. The imprecision of the hand, the change in media, and the new color or thickness of the line all transform the original into a new work of art. Yet the real advantage of the process is the fact that you can improve upon the quality of the line itself. If you are concerned about the material things that constitute a piece of art—namely, the type of pigment and the material of the substrate that accepts that pigment—then it makes all the difference in the world to be able to reproduce an image with new paper and new pigment. In a basic sense, the quality of a line determines the quality of the drawing. The light table allows you to take an original figure and improve it through the reapplication of the line work or mark. In a funny way it is this simple analog tool that best realizes the sci-fi fantasy of being able to limitlessly “enhance” an image.

When tracing a figure on a light table, definition and resolution are affected by the thickness of the papers being used. The thicker the paper, the less light passes through it and the harder it is to make out the figure. If you are tracing, for example, from thin vellum onto lightweight paper, the loss of detail is almost undetectable, but if you’re tracing from one heavyweight paper to another, the limitations are pronounced. What most determines the ability to read a figure while tracing is the contrast within the figure, so an easy way to enhance contrast is by “going over a line” on the original with a heavier, thicker pen or pencil. Very quickly, the act of transferring becomes a multistep process: you redraw and modify an image to make it usable on a light table, then trace it in pencil to capture the forms and general contours, and finally ink it to achieve the finished product.

The act of tracing is the act of capturing a figure’s gestalt. You backlight the original, throw another piece of material in front of it, and all of a sudden you’ve blurred out or abstracted the original, allowing you to read its broader figural mood and not get caught up the details. Tracing via the light table is thus good for capturing the form and geometry of something, but not necessarily its textural style.

The light table is of course limited by its technological simplicity. The thickness of the papers and the brightness of the lamps are the two main parameters that restrict its functionality. If the paper of the original or the new paper is too thick, the figure will not be visible enough to trace. At the same time, if you send too much light through the layered paper, the line begins to lose its definition. The act of tracing, then, is a balancing act. How much thickness can I get away with? How dim can I keep the illumination?

But the interesting thing is that the loss of detail and fidelity that occurs to some degree with any light table tracing is exactly the reason why it can be so exciting to use. The eye sees something different when looking at a figure through a piece of paper and illuminated from below, something different than what a facsimile or Xerox copy affords, and thus a tracing is not just an act of copying, but an act of creation too.

All drawing is meditative, but tracing especially so. The hum of the fluorescent light envelops the artist; the simple and satisfying process of following a line lulls him into a state of peculiar bliss. It is easy to make the link between this meditative activity and the now universal experience of looking into the backlit screen of a computer, but beyond the similarly luminous nature of these two tools, they couldn’t be more different. A computer screen is kept at arm’s length; if you touch it your fingers leave an unsightly smudge. Working at a light table, on the other hand, demands active participation with, and manipulation of, the luminous surface. You use it to apply pigment to paper, by its nature a tactile and physical act. And a light table you don’t just touch; every once in a while, in order to get the perfect tracing, you must even climb onto it.