Our goal, as healthcare architects and designers, is to create a beautiful and functional environment in which healthcare practitioners can provide the best care for residents. At the Chelsea Soldiers’ Home campus in Chelsea, MA, we designed a new Community Living Center (CLC) to replace the existing long-term care facility, planned to be completed by 2021. The current Soldiers’ home was designed following an older model of care, in which residents are organized into large wards, with many Veterans residing in the same room. Dining often occurs bedside or in a large institutional type cafeteria. Large group activities happen in one location, remote from the wards. Our team primarily based the new building at the Soldiers’ Home on the Department of Veterans Affairs Small House Model Design Guide. We incorporated additional planning decisions into the design of the building that stemmed from a review of evidence-based research studying the effect of the built environment on long-term care residents, with most of the research explicitly focused on residents with dementia.

Our team made critical interior planning and design decisions based on the research, including centralized dining and living room spaces within the houses, bright lighting with circadian tuning, a home-like environment that includes positive sensory and safety enhancement and features that allow for personalization by residents. These decisions were necessary to help address common issues for this population of residents, such as confusion, agitation, lack of social engagement, vision impairment, limitations to mobility, sleeplessness and poor food intake. While the built environment cannot address or fix these issues outright, it can assist in the supportive care of residents.

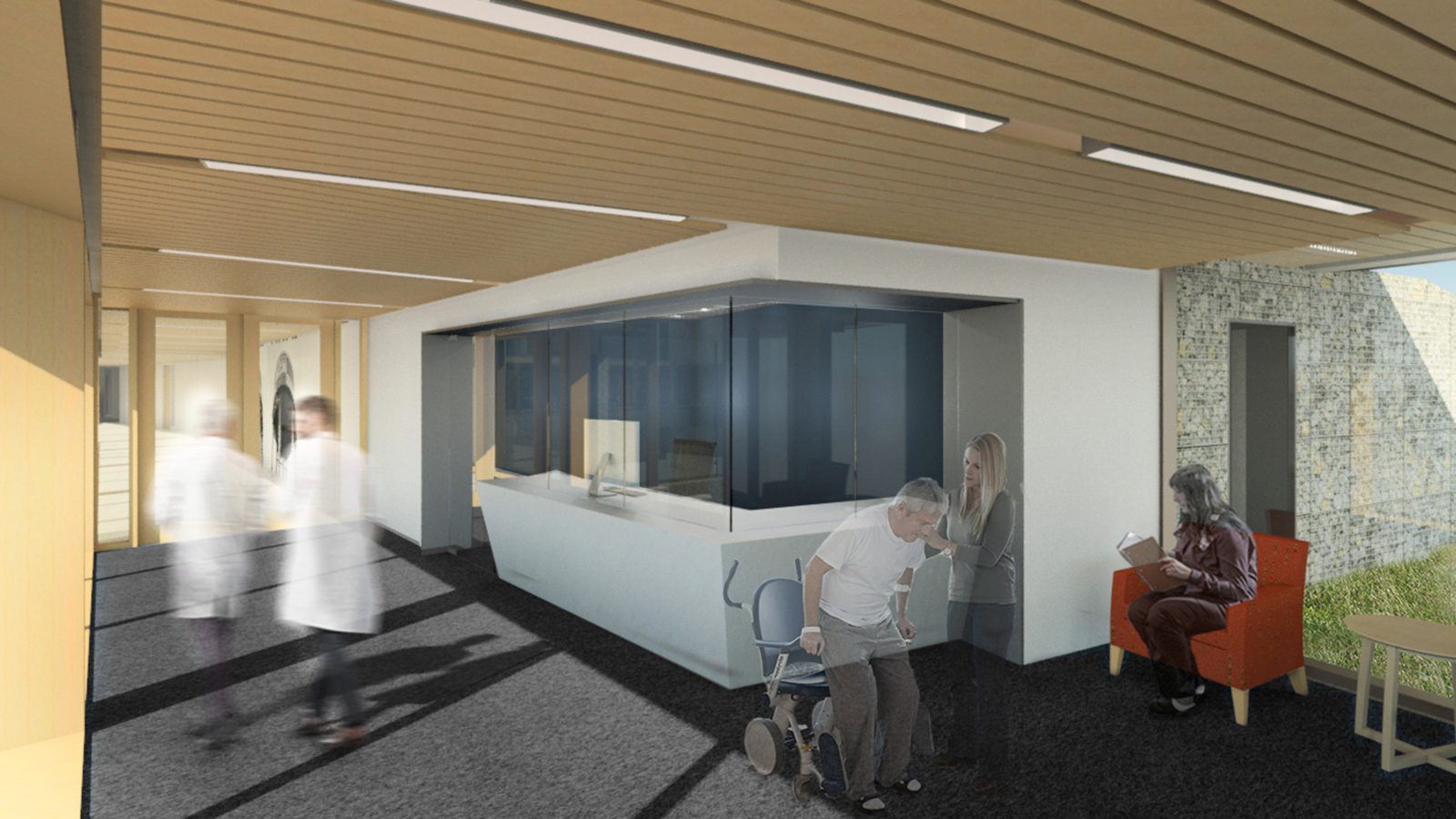

In the new care facility, each floor is divided into two houses, which have groupings of seven private rooms on the east and west wings of the building. These private rooms are supported by a central kitchen and dining area, for exclusive use by the residents of that house. A 2009 study conducted by the Department of Architecture at Dresden University of Technology (Marquardt & Schmieg, 2009) found that providing only a single living room and dining room adjacent to the resident’s rooms, in addition to simple straight circulation to locations of relevance, significantly improved resident’s wayfinding ability. Creating open sightlines for residents will give them familiar “signposts” to use while orienting themselves within each house.

With the help of ARUP’s lighting design group, we gave special consideration to the overall lighting levels and design within the houses. In spaces for the elderly, code requires higher lighting levels, but several studies have revealed that increasing the overall lighting can also improve a dementia resident’s function and sense of well-being (Garre-Olmo et al., 2012). Additional research has shown that providing high contrast at the dining table and increasing the lighting levels can improve food intake (Brush et al., (2002), Koss & Gilmore, 1998). We designed a custom light feature above the dining room to provide even dimmable ambient light and included bright track lights on either side of the feature lighting to increase the contrast at the table settings. We also included circadian tuned lighting features in the public spaces, the therapy bathing suite and the resident rooms, which is shown to decrease agitation (La Garce, 2004).

Many studies have reviewed the impact of noise on residents with dementia. The consensus, to create an ideal situation in which agitation is low and social engagement are high, is to provide a pleasant level of noise that gives the motivation to participate without overstimulation (Cohen-Mansfield & Werner, 1995, Meyet et al., 1992). Creating a home-like environment has also been shown by several studies to advance the overall quality of life for residents and even improve some of the care outcomes (Charras et al., 2010; Garcia et al., 2012). The living room, which functions as part of the heart of each house, has the potential to create a significant amount of ambient noise if not carefully designed.

Since it was essential to create a light-filled and relaxing home-like environment, with a positive stimulus that doesn’t create too much activity or noise, only a single television has been designed into the space. This is in contrast to the existing wards that have a small TV at each bed. An additional television for more private viewing is provided in the enclosed den, for reduction of competing noise. Staff stations are decentralized, and the staff home office is in an enclosed location, which can help reduce unnecessary or loud staff interactions and promote a peaceful environment.

Providing carpets and rugs to dampen noise and create a cozier feel was not an option due to the infection control and housekeeping requirements of the facility. As a result, the team designed other home-like features for the living room and some of the larger activity spaces. In the home and at the great rooms on Level 1 and Level 5, a vapor “fireplace” creates a soothing and inviting focal point, without the danger of fire or the cost of hard-piped gas. Each resident room also includes features like a cozy window bench, desk with open shelving for personalization, and a cleanable upholstered headboard, with concealed medical gases. When residents have the freedom to personalize the entry to their bedrooms with photographs, they are better able to locate them (Gross et al., 2004), so a customizable niche and mailbox at the room entry was also included in the design.

I hope that by including a research component to our design, we can provide the staff and residents with a comprehensive and functional design that allows for the best care for Veterans.

References:

1. Marquardt, G., Bueter, K., & Motzek, T. (2014). Impact of the Design of the Built Environment on People with Dementia: An Evidence-Based Review. Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 8(1), 127-157.

2. Brush, J. A., Meehan, R. A., & Calkins, M. P. (2002). Using the environment to improve intake for people with dementia. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly, 3(4), 330-338.

3. Charras, K., Zeisel, J. B. J., Drunat, O., Sebbagh, M., Gridel, M., & Bahon, F. (2010). Effect of personalization of private spaces in special care units on institutionalized elderly with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Non-pharmacological Therapies in Dementia, 1(2), 121-137.

4. Cohen-Mansfield, J., & Werner, P. (1995). Environmental influences on agitation: An integrative summary of an observational study. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 10(1), 32-39

5. Garcia, L. J., Herbert, M., Kozak, J., Senecal, I., Slaughter, S. E., Aminzadeh, F., … Eliasziw, M. (2012). Perceptions of family and staff on the role of the environment in long-term care homes for people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 24(5), 753-765.

6. Garre-Olmo, J., Lopez-Pousa, S., Turon-Estrasa, A., Juvinya, D., Ballester, D., & Vilalta-France, J. (2012). Environmental determinants of quality of life in nursing home residents with severe dementia. Journal of the America Geriatrics Society, 60(7), 123-1236

7. Gross, J., Harmon, M. E., Meyers, R. A., Evans, R. L., Kay, N. R., Rodriguez-Charbonier, S., & Herzon, T. R. (2004). Recognition of self among persons with dementia: Pictures versus names as environmental supports. Environment and Behavior, 36(3), 424-454.

8. Koss, E. & Gilmore, G. C. (1998). Environmental interventions and functionality of AD patients. In B Vellas (Ed.), Research and practice in Alzheimer’s disease (pp.185-191). Paris, New York, NY: Serdi/ Springer

9. La Garce, M. (2004). Daylight interventions and Alzheimer’s behaviors: A twelve-month study. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 21(3), 257-269.

10. Marquardt, G., & Schmieg, P. (2009). Dementia-friendly architecture: Environments that facilitate wayfinding in nursing homes. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 24(4), 333-340

Related Links:

Reinventing the Elder Care Environment

Pushing the Envelope: Net Zero Healthcare

Iconic Water Tower Demolished for Chelsea Soldiers’ Home