After several debates around the office, including formal lectures, blog posts and water cooler talks, it is clear that modes of representation are of interest. Recently, the conversation at PAYETTE has been dominated by the idea of sketching and its recession within the practice of architecture. I aim to expand this conversation to include physical modeling and its similar decline within the design process.

Modeling is a practice that all architecture students are instructed to use as a way in which to explore and examine a design more holistically. It allows the designer to combine the information of section, plan and axon while providing a way for the viewer to see the space that the design creates. Physical models allow the designer to freely negotiate the space with a design and truly see the design’s spatial impact. Even computer models and rendering, which convey a similar amount of information, are limited to a single vantage point of a two-dimensional representation.

While the highly crafted model of fine materials is still prevalent within most design practices, I believe those models are not a method for design exploration, but rather an artifact memorializing a design upon completion. The study model however, is at its core only an exploration of design, not intended to represent a building in its entirety but to portray a single aspect of the design, similar to a sketch or a diagram. Its beauty often lies in its imprecision with quick and dirty cuts, ripped or torn pieces taped on in a seemingly haphazard way. This is where the potential of the study model lies, through its ability for the designer, and others, to dive deeper into the understanding of a project. Like a quick sketch, the study model has the potential to allow designers to explore ideas and concepts that reveal themselves only through the physicality of the model – perhaps ideas that would not have come to fruition without the model. The physical model serves as a way to channel a stream of consciousness into a three dimensional representation.

And yet, it seems modeling has taken a back seat role in the design process, if it even has a role at all. The process of quick study models has been surpassed by the ease of current computer modeling software. While computer modeling often seems faster than building a model, speed isn’t the only objective. The emulation of space produced in a computer rendering provides a different avenue for exploration and analysis, while the physical models allows for a physical examination of space. So what has happened? Why do we hesitate to get dirty and slap some chipboard together?

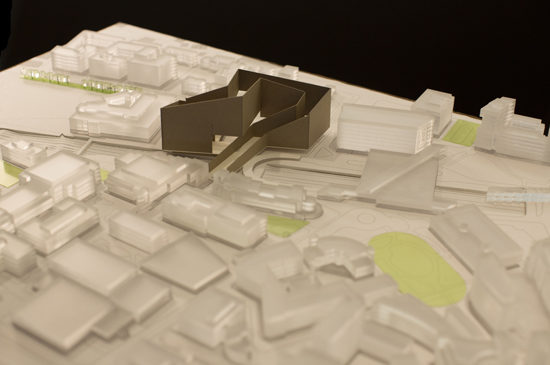

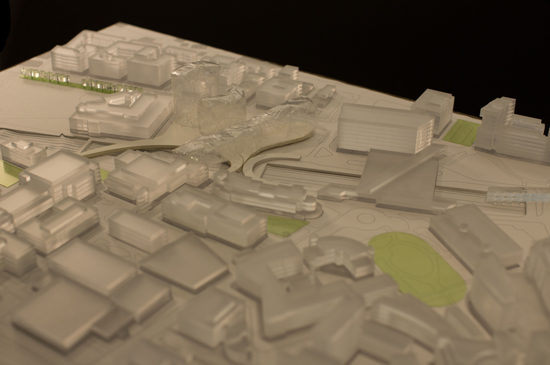

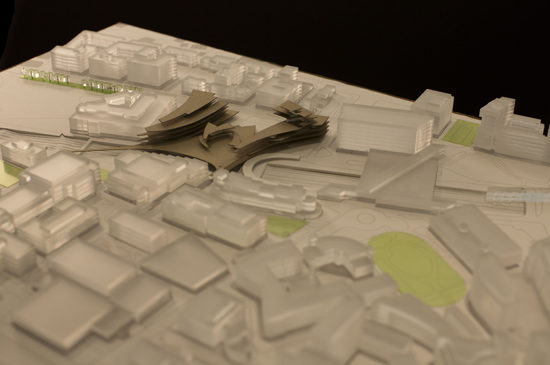

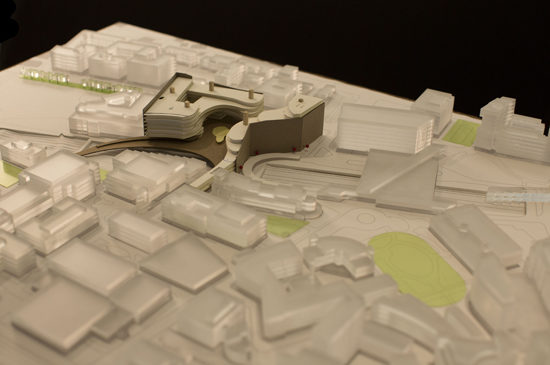

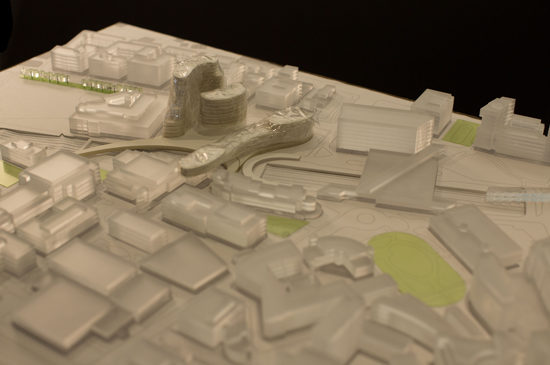

PAYETTE recently competed for a new science research building and highlighted modeling as a primary means of design exploration. At the outset, the team modeled several designs and multiple iterations of those designs, using everything from chip board to left over rubber samples. Through this charette of modeling the team explored the site and the impacts of the designs more holistically than possible with any two-dimensional representations. The resulting discussions over this sea of models were amazing, and every model, no matter how quick or sloppy, posed great questions for the design team to consider. At one point people within the office joined the discussion and began altering the models with scraps paper lying around the office, or removed piece from one model and added to another. This process undoubtedly pushed the design to a remarkable new place that none of the designers could have conceived at the start of the competition. While it is impossible to attribute the success of this design to the modeling process alone, it is equally impossible to deny that its contribution to the success of the design. This process took a little under a week and our relatively small team was able to produce around 40 models.

So the question remains, why have quick study models become so rare within the design process? Modeling is a skill that we all have and whether its folded paper or stacked foam, study models have the power to push the design process much farther than may be apparent.