What is healthcare architecture and why is it important?

Though rational considerations of layout and clinical processes are frequently prioritized, healthcare architecture isn’t comprehensive if it does not consider the human experience. People generally experience healthcare architecture at their most vulnerable moments, and it becomes the mission of designers to provide comfort and reassurance for these people. Most of us are born in a hospital, and many spend their last days in one as well. We interact and rely on the healthcare system, yet in many cases the experiential and personal quality of these environments is overlooked.

I was initially drawn to the complexity of the field of healthcare design; the merging of technical and poetic resolution, where each project is a puzzle of functional relations, with its own unique solution. In academia and practice, we frequently discuss the importance of bringing humanity to these spaces; the sensitive nature of events and emotions that occur in these rooms. We talk about the patient and staff experience of the environments we design, hoping to bring the highest level of satisfaction to both parties without compromising the design intent. While working at PAYETTE, I had the opportunity to experience and understand first-hand what healthcare architecture is about, and why it is important; while technical aspects of design are vital, the human experience of patients and staff is at the heart of our work.

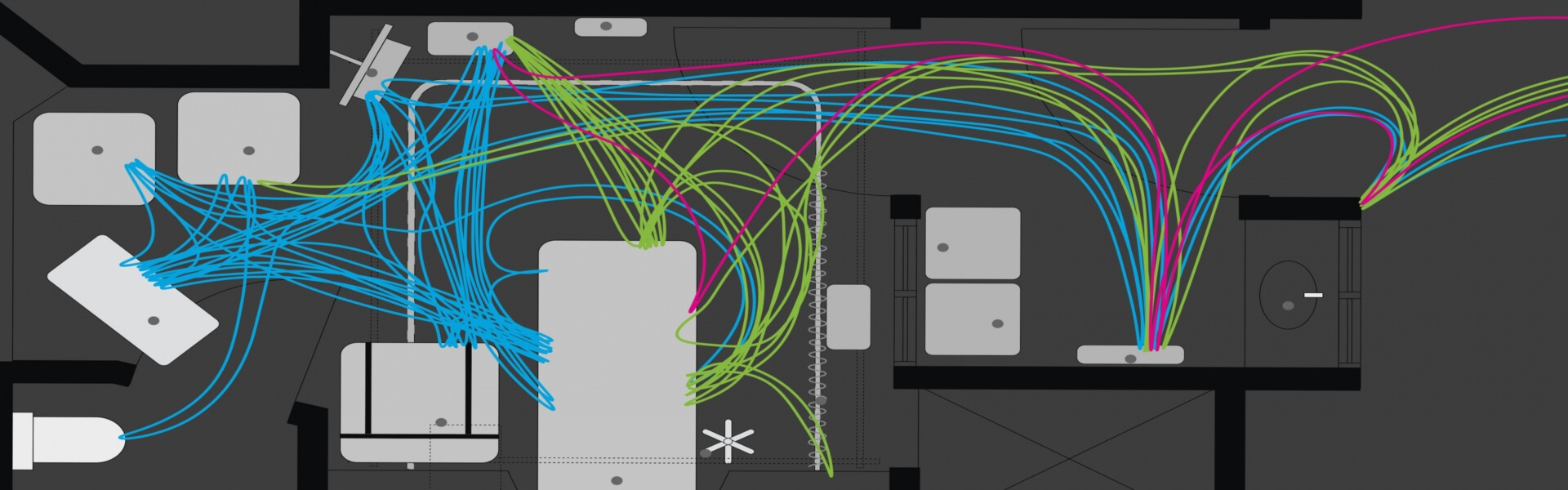

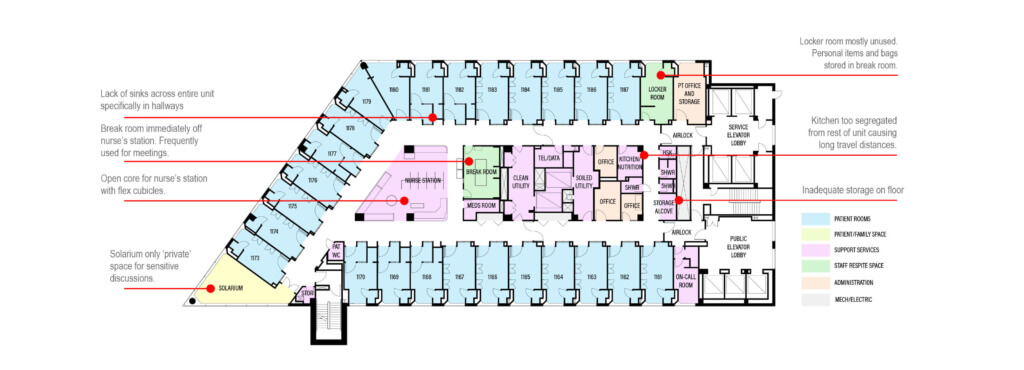

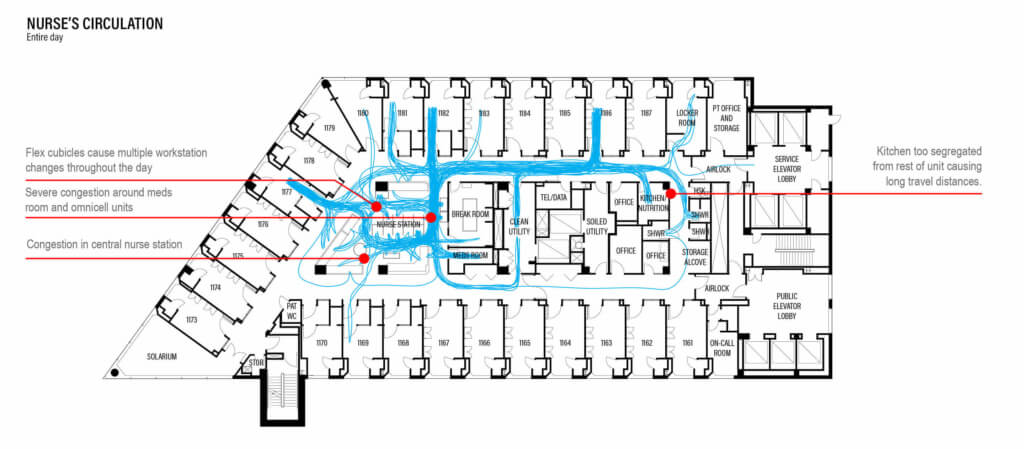

My observation consisted of forty-five hours at an inpatient Oncology Unit. I divided my time into twelve-hour increments and completed my observation over two weeks. I had the opportunity to shadow several different nurses in the unit, which is decades old and consists mostly of double-occupancy patient rooms.

During my time there, I was struck by the intense and stressful environment in which the nurses work. Being on an inpatient floor was a sensory overload; alarms were going off every few minutes from patients getting out of their beds, monitors beeped constantly, and the nurses were on the move all day. There was little natural light in the staff’s main workspace and an overwhelming smell of cleaning chemicals in the air. I asked the nurses how they felt about the working environment and they consistently highlighted the stress of the incessant noise and physical responsiveness required of them. Despite this, the nurses are a dedicated and caring group of individuals. Even in harsh conditions with terminally ill patients, they remain dedicated to providing their patients with exemplary care.

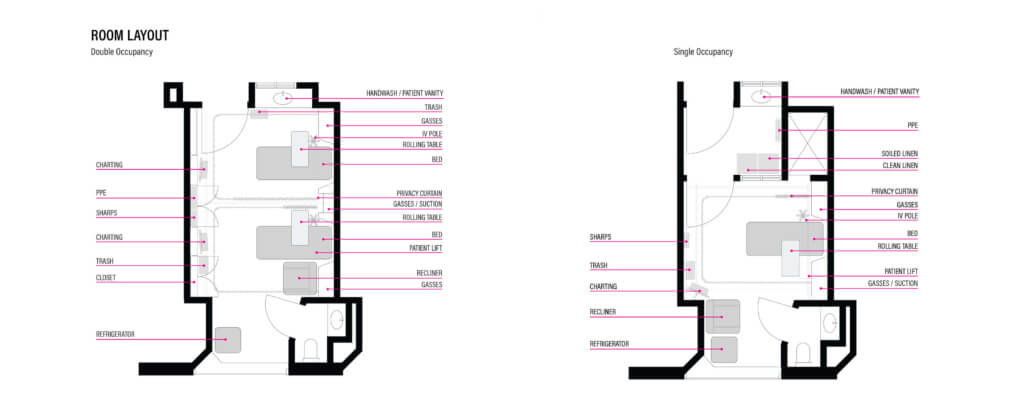

For many of the immobilized patients, the visitation of friends and family was the highlight of their day. However, the double-occupancy rooms provided little space for guests. Since two patients were in the room at all times, visitors were forced to sit to one side of the room behind a curtain visually separating the two beds. In some cases, care was being delivered and discussed in one side of the room while visitors sat and spent time with their loved ones on the other side. The absence of a dedicated family space in the rooms created an environment which lacked privacy and intimacy; families frequently gathered loose chairs or stood to the side of the bed if no chairs were available, leaving them uncomfortable and often standing over their loved one. The rooms didn’t have adequate shelving for personal items to be displayed, leaving no room for gifts or even a simple photograph. This was particularly distressing for terminally ill patients who spend extended time in the hospital. For patient rooms that become a person’s last home, the ability to customize and make a space home-like is vital.

My observation showed me that peoples’ experiences are at the heart of healthcare architecture. Having seen what a substantial impact the design of the built environment can have on the delivery of patient care was striking. I learned how important simple elements of a design can be, such as natural light, a space for family and personal items, as well as respite for staff. Circulation and critical adjacencies are important, but what we do as healthcare designers is truly about people and relationships. We are charged with creating spaces that embody ideals that are generally contradictory: functional yet beautiful, sterile yet comforting, controlled yet healing. We are tasked with humanizing some of the most delicate moments of life and providing spaces to accommodate these moments, whether they are clinical or emotional in nature.

The lessons I learned during my observation will be some of the most important of my career; I will carry them with me and they will help me become a better healthcare designer.