The Space Strategies team has been engaged in lab planning work for a diverse range of typologies and research communities over the past year, including the Sustainable Engineering Laboratories building at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, a life sciences building for a confidential university client, and planning efforts at Tulane University and the University of California Berkeley. There have been a wide range of takeaways and lessons from these efforts and, considering the broad spectrum of research types represented by these projects, there have been a few important, overarching takeaways that point towards future trends for research – and therefore for research planning.

DISSOLVING BOUNDARIES

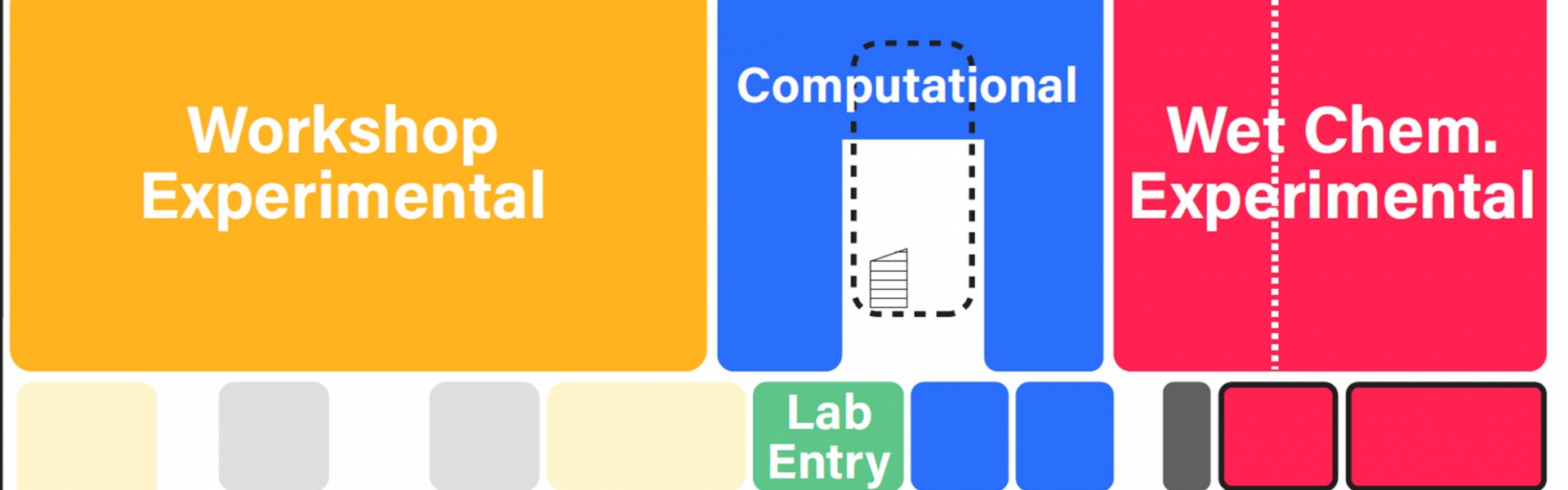

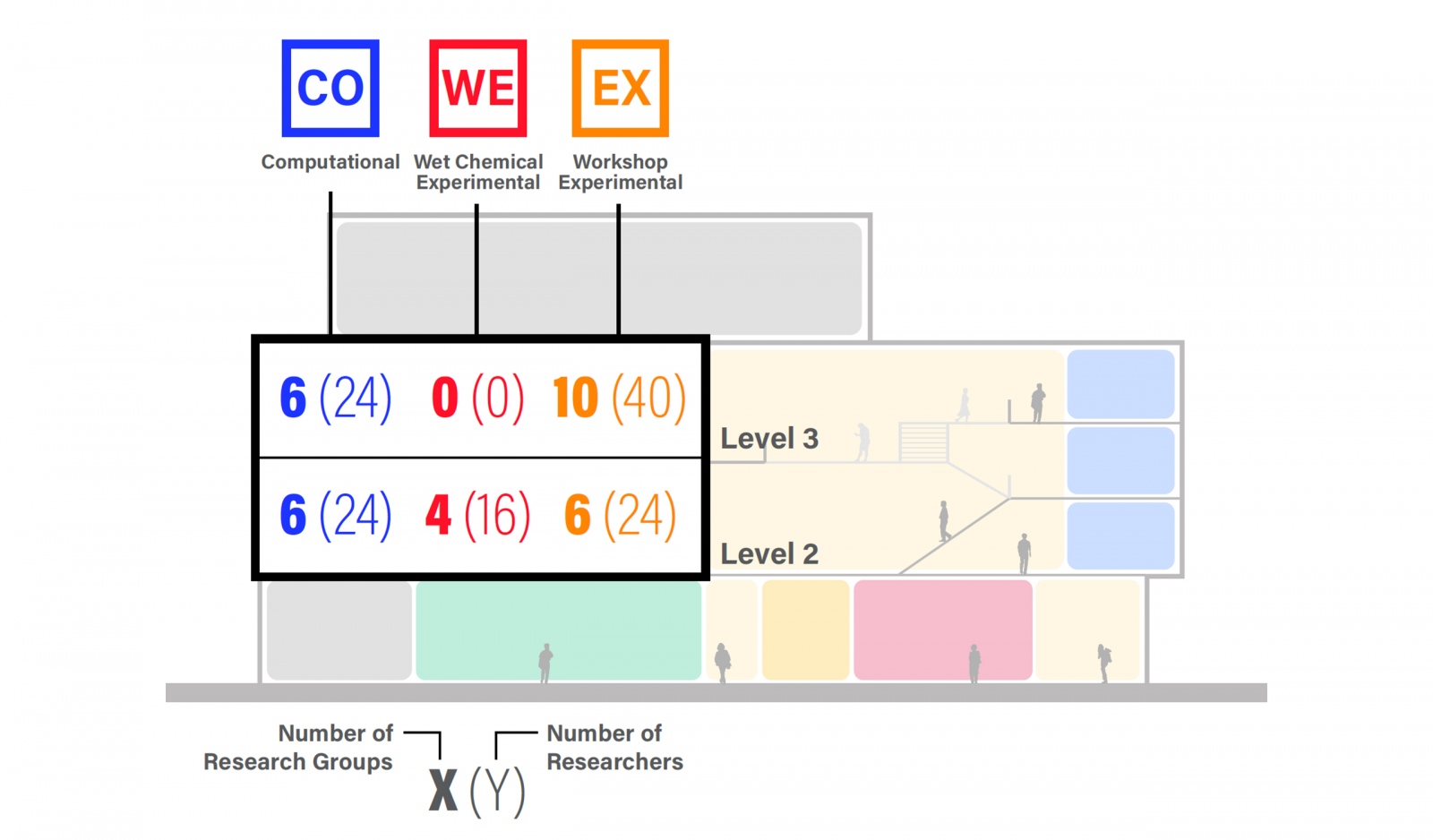

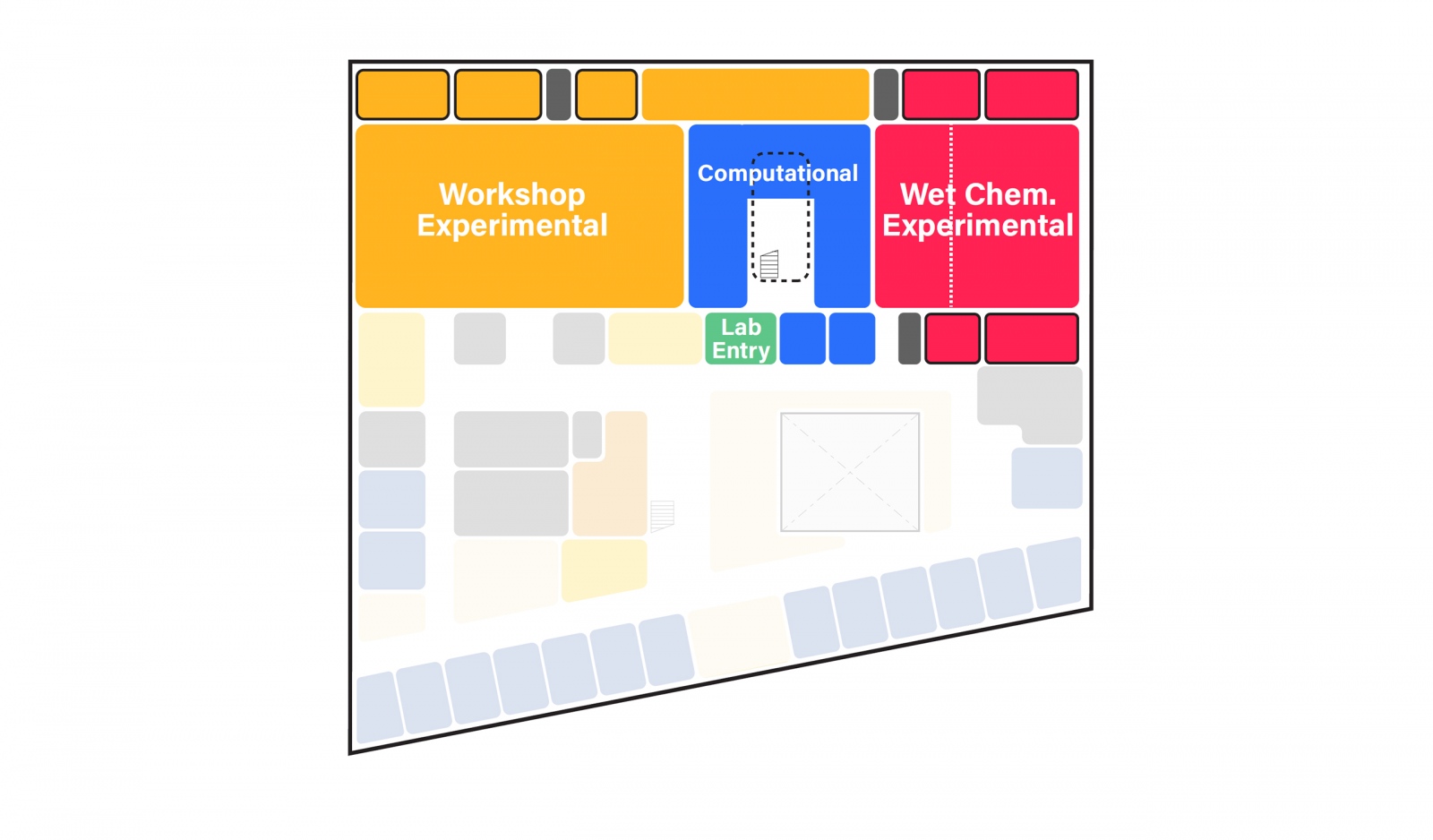

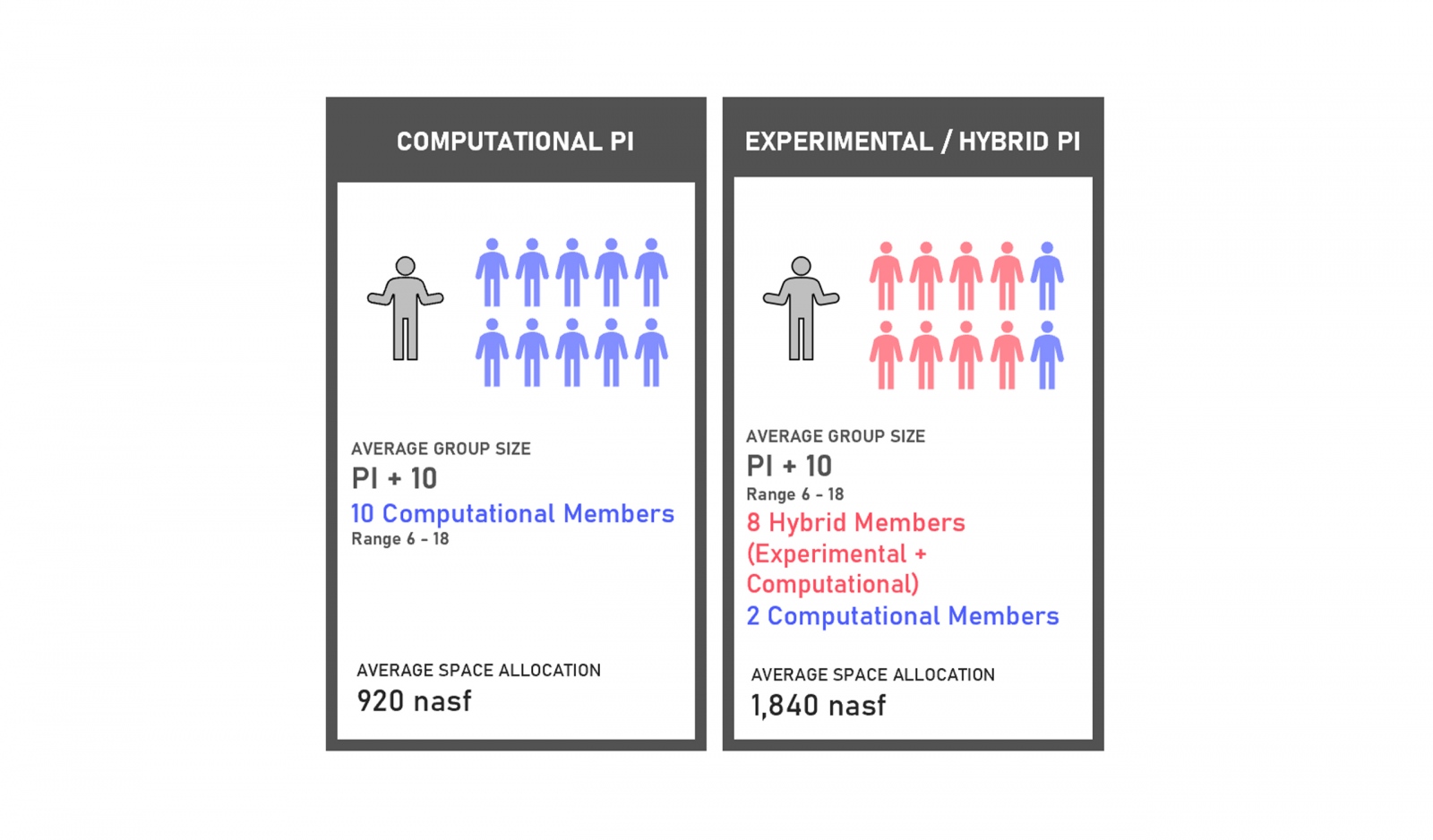

The first major theme has been the dissolution of boundaries between experimental research – the kind of research that takes place mostly at lab benches and specialized lab spaces like tissue culture rooms and imaging stations, which requires high air change rates and other MEP considerations – and computational research, which as the name suggests is largely undertaken digitally with computing power and can be done outside of the lab proper. Traditionally, one might expect a lab group, led by a faculty member or Principal Investigator (PI) to be essentially either computational or experimental depending on the faculty member’s background and area of expertise. However, this model has been shifting to more hybrid lab groups, where, within a single lab group, there may be several members performing experimental research in the lab, and several members performing computational analysis of those experiments. Hybrid experimental groups –80% experimental and 20% computational – were the basis of space planning for our confidential client, and spatial integration of computational and experimental groups were fundamental to the research organization of both our confidential client and UMass.

That trend is accelerating – many institutions, at a fundamental level, have begun to see the future of research as increasingly computational given the rapid increases in computational power and imaging capabilities. According to one faculty researcher the Space Strategies team recently worked with, there are microscope systems currently in use in their department which generate 30TB of data from a single image; the size of these images will only increase over time. Analyzing a series of those images has serious implications on both computational time and space (space for a greater number of computational researchers, and more backend support, like server room space, for computational power). Therefore, the dialogue between researchers performing the experiments in the lab and those performing computational analysis of the experiments is growing ever more important. Even lab groups comprised solely of computational researchers are often working closely with data sets of experimental researchers; all of this increasing emphasis on computational research then points to the need for space planning which both accommodates larger computational populations and their attendant needs, and integrates those researchers with the experimental researcher population.

CULTURE OF RESEARCH COMMUNITIES

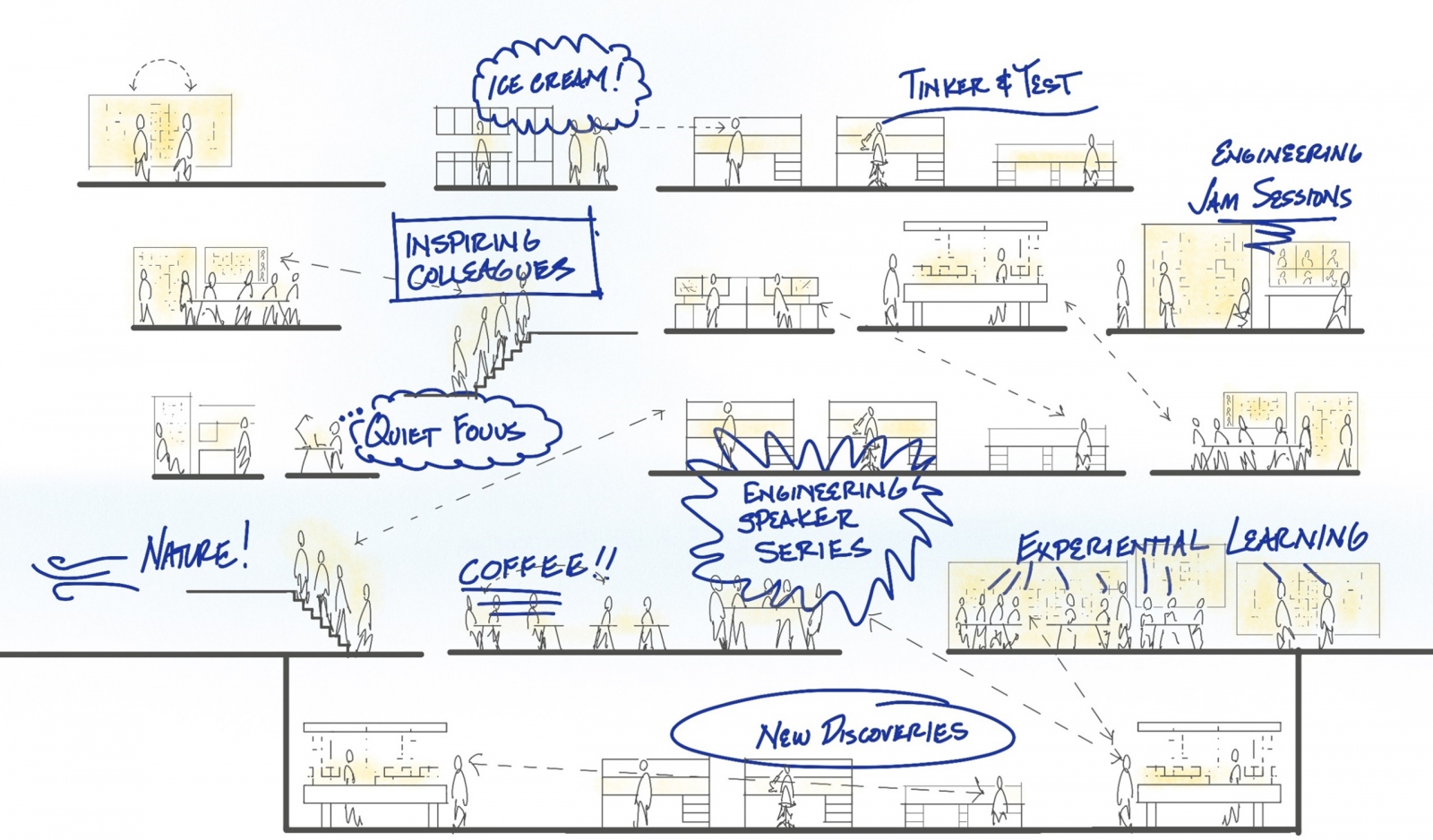

The second major theme across this range of projects has been the emphasis on the culture of research communities, and the importance of culture in producing highly functional research teams. The Space Strategies team often works with user groups to define the needs and spatial parameters of research and research-adjacent spaces: labs, lab support rooms, experimental and computational write-up desking areas, offices and collaboration/meeting spaces. These user groups often, but not always, are currently housed in older, challenged buildings which often have varying levels of MEP deficiencies, outdated lab planning concepts, limited space, challenging floor-to-floor heights and many other compromised conditions. However, research groups in these older buildings have often adapted tactically to their conditions and have produced social and collaboration models which work around the limitations of their space. Faculty members and researchers therefore often have a keen insight into what specific obstacles, if removed in new space planning, would enable greater efficiency and/or collaboration.

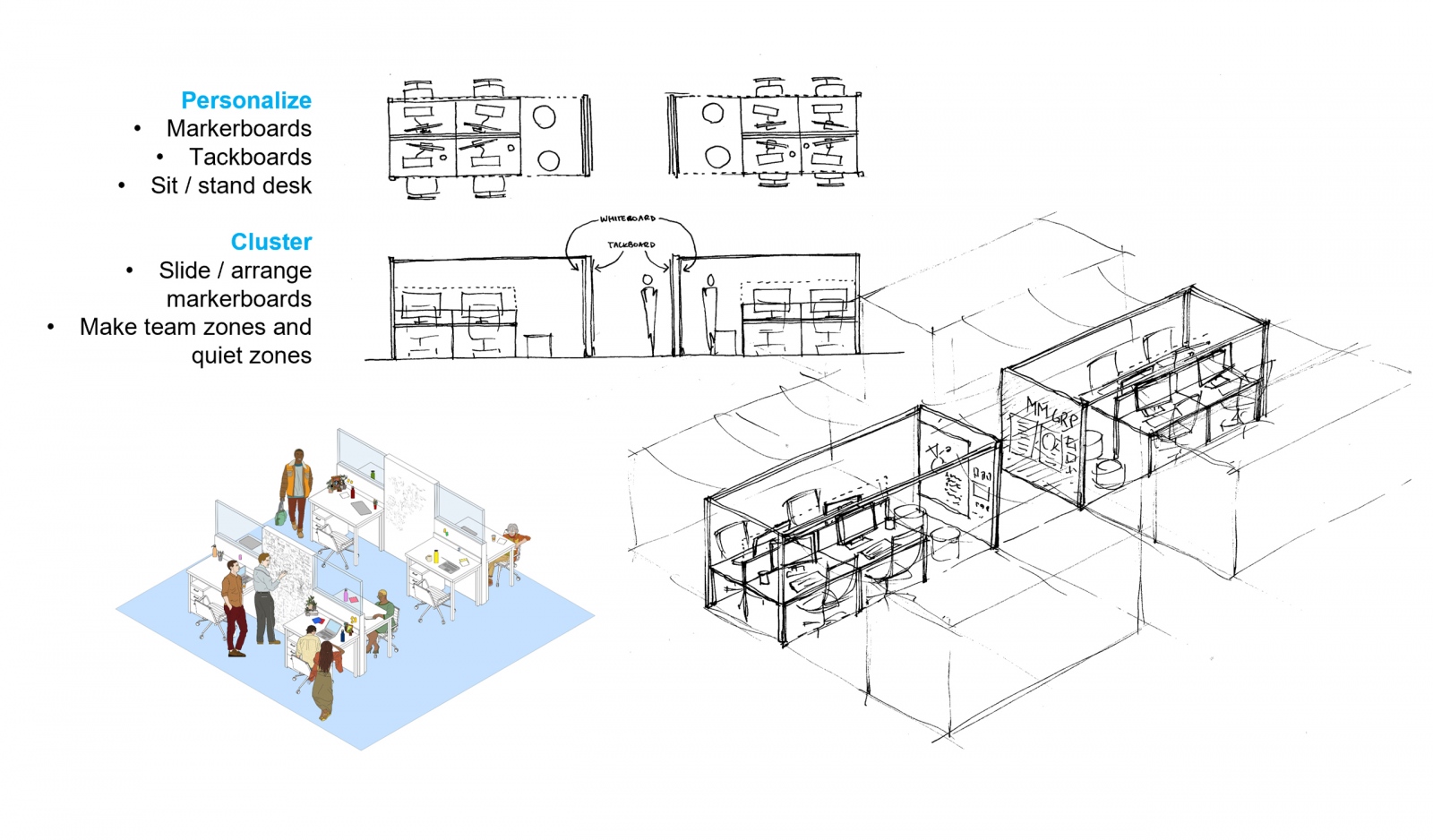

What has emerged in many of these projects, when discussing the whole portfolio of research-adjacent space, is a focus on how the existing culture of research can be maintained and strategically enhanced through the planning and design process. In some cases, faculty members have frequently mentioned the desire to have their research groups’ assigned desk spaces close at hand to the faculty members’ office space, rather than locating all of the faculty office spaces together “down the hall.” Research group members frequently mention the desire to have some ability to personalize their assigned desk spaces and create contiguous units of lab group desks to foster camaraderie and group cohesion within lab groups. They also emphasize the need to, despite not having assigned office spaces themselves, occasionally have private phone or Zoom conversations, and need access to spaces which allow them to have these conversations. Lab managers frequently mention the need for logistics spaces – shipping and receiving, lab waste pickup zones, consumables storage – that allow research groups to use their lab space as efficiently as possible. This all points to a user group engagement process that is strategically similar across projects – discovering and designing towards an ethos of research community – that is nevertheless very flexible and often quite different between projects, and which often yields divergent results in terms of space needs and space planning.