At its core the Spatial Equity Research Group is interested in design through the lens of social equity, diversity and inclusion. This post continues to explore how architects and designers can integrate equity into their practice.

PAYETTE’s Spatial Equity Research Group investigates how design excellence can expand to consider the voices of neurodiverse populations. Our research has encouraged us to reach out to the community through one-on-one conversations, user surveys and workshops. This includes engaging with health experts who work with individuals with autism, teachers in neurodiverse spaces and targeting individuals with a range of sensory considerations through our Lab Gap! survey. By directly communicating with the community we are designing for, we have learned there is not one simple solution toward an equitable design strategy for neuro-inclusion. Instead, a one-size-fits-one approach leads to a more tailored space, but how can we design successful buildings with this in mind? To explore this topic, we have started to look at the possibilities for designing “neuro-inclusive” spaces.

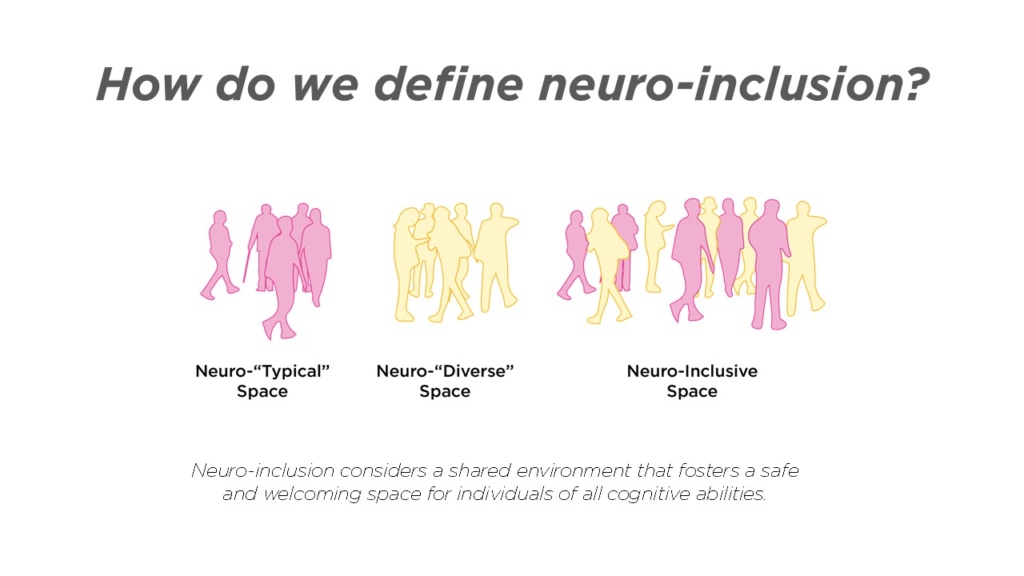

The term neuro-inclusion considers how we can shape our spaces to provide a sense of safety, promote inclusion and offer a welcoming environment. We recognize that this may not be suitable for all types of building programs. Alternatively, providing spaces that specifically meet the needs of individuals who are neurodiverse is an appropriate option to consider.

Our thoughts on designing a neuro-inclusive environment recognize the variety of space types for various sensory needs that may be required – loud and quiet, large and small, soft and vibrant patterns and everything in between. These dichotomies take into consideration multiple sensory considerations such as visual, audible, environmental, social, cognitive and physical. By acknowledging the large scale of sensory needs and preferences, how can we as architects design inclusive, safe and welcoming spaces?

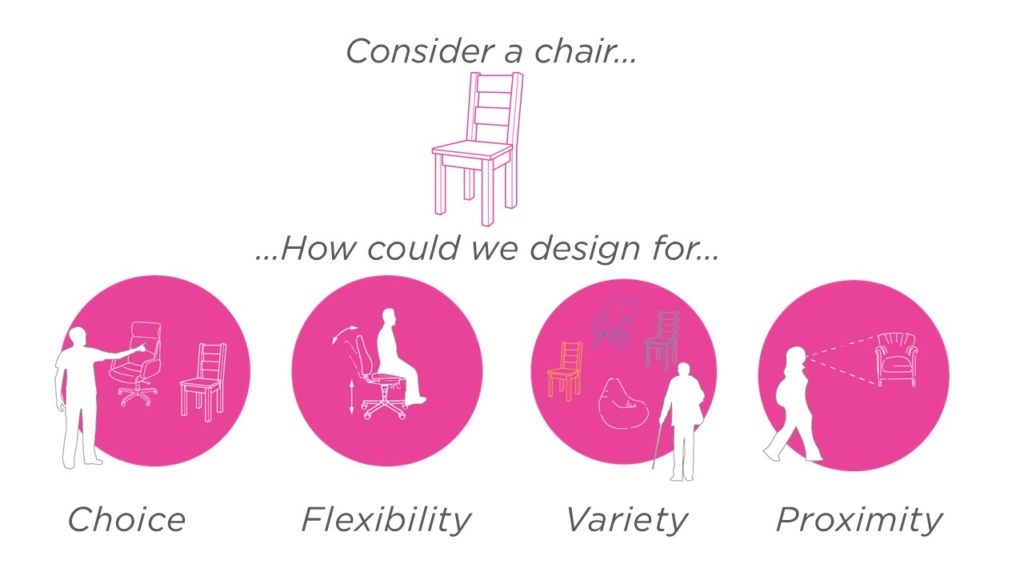

We have been using the design of a chair as an analogy for spatial characteristics to consider. Freedom of choice provides individuals with the autonomy to make decisions that best suit their needs. Flexibility can be finetuned by individuals, providing them with power and control over their environment. Variety considers things such as ranges in texture, color, scale, etc. to provide options. Proximity is a critical component that threads Choice, Flexibility and Variety together. By considering the proximity of these design decisions to where and how people could access them can lead to either the positive intended use of the space or failure.

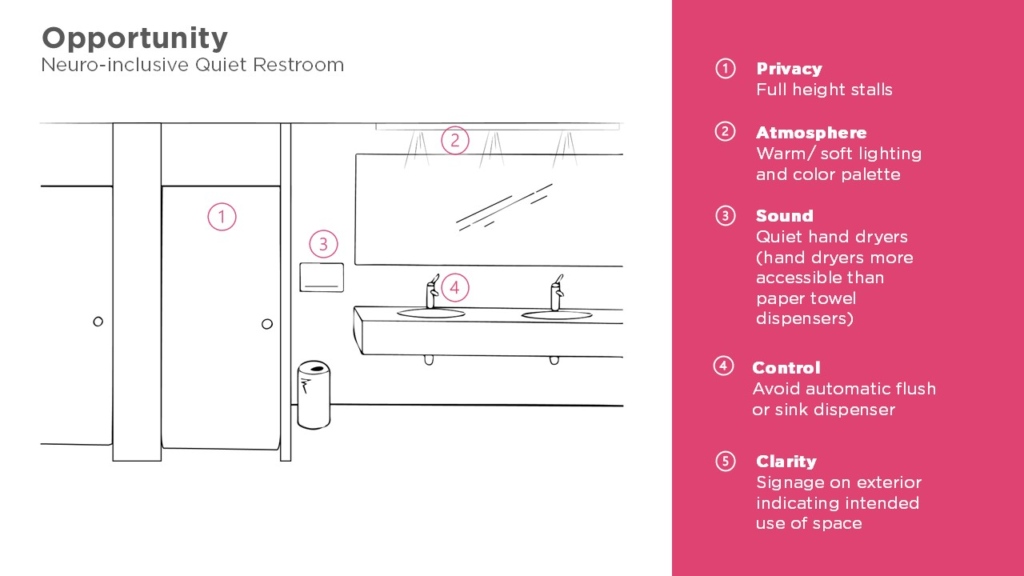

The public restroom is a case study that the Spatial Equity Research Group has been iterating on. We have learned that public restrooms can include an overwhelming number of sensory experiences. So much so, that some neurodiverse individuals may avoid using public restrooms. This can be due to a variety of factors including sudden noises from automatic hand dryers and automatic flush toilets, harsh lighting, odors and confusing signage. The Ability Toolbox has highlighted some of these experiences as well as design considerations, which include color, texture, lighting, smells and noise.

By considering a few simple design possibilities we could design public restrooms in a way that not only supports individuals with a variety of sensory considerations, but also fits the needs of neuro-typical individuals. A few simple decisions as outlined below are intended to provide a better design and encompass a breadth of needs, while not making or breaking the budget.

Privacy: Full-height stalls provide all individuals with a greater sense of security and social separation from others who may be using the restroom. Increased privacy can help reduce anxiety and provide safe social and environmental (odor, touch, etc.) barriers. Public restrooms inherently have a variety of restroom sizes – small single stalls, ambulatory stalls and ADA/family stalls. This by design provides a variety of options for users. However, some users may avoid stalls that are next to the sinks, or middle stalls that provide less privacy. The addition of full-height stalls expands the user group that is able to access them comfortably– families, individuals with disabilities, neurodiverse individuals and the LGBTQ+ community. To provide users with more choices, different restroom types (single user, multi-stall, etc.) can be dispersed throughout a building. With this option, proximity to users, wayfinding and signage are critical components to providing inclusive access.

Atmosphere: Harsh white or blue lighting, flickering lighting and dim lighting are all factors that contribute to a negative visual experience. Discussing potential options with users for warm lighting and soft color palettes should be considered early in the design process. There may be cases where individuals prefer more stimuli and lean toward more saturated colors. These topics should be discussed with users early on to determine the degree of variety and choice that is appropriate. For example, bright lighting could be appropriate for some users while the incorporation of dimmers could provide all users with a choice and flexibility of lighting options.

Sound: Automatic hand dryers, faucets and toilets can produce sudden loud and disruptive noises. This may be startling and overstimulating for some individuals. Opting for quiet hand dryers and manual flush toilets can provide users with more control over their environment and noise levels. With manually operated facilities, users have greater choice regarding when loud or disruptive noises occur. This also reduces the amount of sudden noises produced by other users. Alternatively, if auto-flush toilets are already in place, a retrofit of sensor blocking covers can be put in place to give users a choice regarding when loud noises occur.

Control: A sense of control goes hand in hand with freedom of choice over one’s environment, provoking a sense of safety and welcoming atmosphere. This sense of control can take many shapes. For example, temperature control at faucets, choice over how to dry your hands (paper towel vs. air dryer) or choice of soap (fragrant vs. non-scented). A challenging component of designing for neuro-inclusion is that it often takes the form of a one-size-fits-one approach rather than one-size-fits-all. We advocate for discussion with your users any specific needs. For example, there may be a preference toward no touch or minimal interaction with surfaces due to potential exposure to germs versus surfaces and fixtures that can be manually operated for individual control.

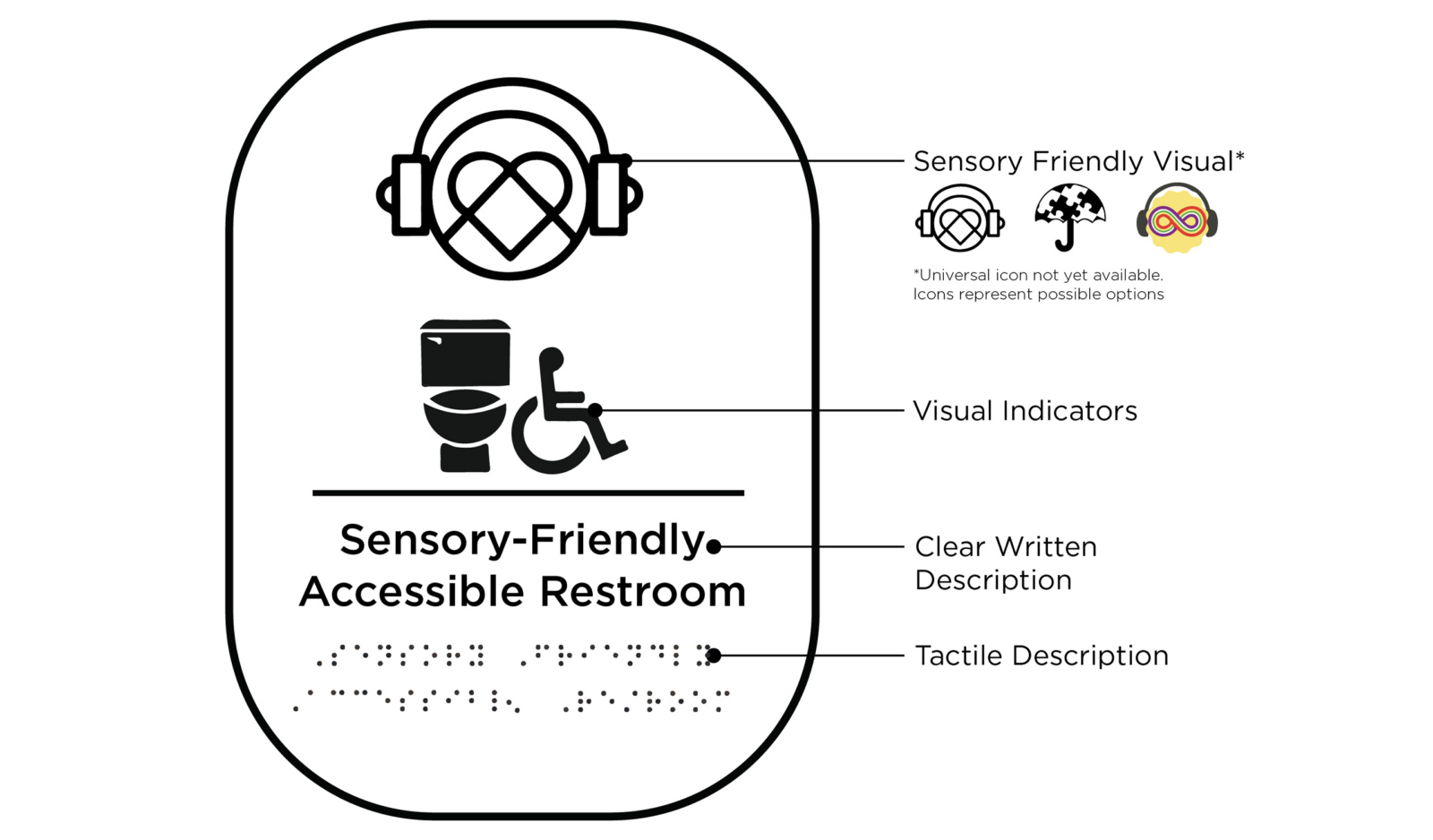

Clarity: Without clear wayfinding and signage indicating a restroom’s amenities, individuals have little way to understand that the facility can be used by them. At a minimum, exterior signage should include pictorial and written graphics for varying cognitive abilities that signal the different design amenities included. Visible signage at restroom entries helps alert individuals to the proximity of facilities, without which confusion over where restrooms are located and the amenities for each becomes ambiguous.

Another approach to designing restrooms for neurodiverse individuals is to provide a variety of restroom types throughout a building. Notably MIT’s Office of Campus Planning provides a set of design guidelines that includes offering three different restroom types. Single-sex multi-user restrooms, which provides separate spaces for men and women. Inclusive single-user restrooms, which are fully private and support caregivers. Inclusive multi-user restrooms, which can be used by people of varying abilities.

Similarly, the Boston Musuem of Science provides access to multiple restroom types, including sensory-friendly restrooms where auto flush and auto hand dryers are replaced with manual sensory friendly options. They describe where each type is located on their webpage. The graphics below represents possible signage options.

As architects we can and should discuss options for more inclusive restrooms with our clients. Often the question of cost arises during these conversations. Will making these choices for a neuro-inclusive restroom cost more? We would argue that items such as manual flush toilets, soft lighting, etc. are meant to be options that are little to no additional cost to their counterparts (automatic flush toilets, bright white lighting, etc.) Therefore, by making some of these subtle design decisions we can not only provide a restroom that is neuro-inclusive, but also one that is safe and comfortable for everyone to use.

We continue to investigate the ways in which restrooms and other public spaces can accommodate a variety of user needs. Conversing with users and diving into design research allows us to be nimble and flexible regarding our design decisions. The above design suggestions are intended to be guidelines for design and act as conversation starters for your own user engagements.

Resources

https://campusplanning.mit.edu/initiatives/inclusive-restrooms

https://architectureandaccess.com.au/design-for-neurodiversity/

https://theabilitytoolbox.com/sensory-friendly-bathroom-design/

https://www.mos.org/visit/accessibility