At its core the Spatial Equity Research Group is interested in design through the lens of social equity, diversity, and inclusion. This post is the third in a series exploring equitable design standards.

Definition

While the principles of Accessible Design are outlined in the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the focus of Accessible Design is to ensure that spaces, objects and interfaces can be used by people with auditory, cognitive, physical and visual impairments. As a design process, accessibility allows for the explicit consideration of people with disabilities in product design, software design, web interface development and architecture. The design characteristics include facilitating independence for people with a variety of disabilities and emphasizing safety.

Accessibility vs. Inclusivity

Accessibility looks at standards for guidance and usually addresses “typical” vs. “disabled” populations. It places a stronger emphasis on specific cognitive and physical disabilities and creates design solutions for those particular users.

Inclusive Design asserts that there is no “typical” person. It understands that exclusion can happen at any level. Inclusive Design is a process-based methodology and will be the topic of the next blog post in the series.

History

Because the Accessible Design movement was crucial to the important events and legislative efforts associated with the ADA, they have a shared history which can be explored further in our previous post, Spatial Equity: Designing Beyond ADA. The movement began post World War 2 as industrialization created standardization in living and working spaces and amenities. As a result the lack of individualization in design in tandem with injured veterans seeking higher educational experience prompted investigation in accessible design. Disability rights were later integral to the Civil Rights Movement.

In 1948, The University of Illinois was the first to admit 13 new students with disabilities at a satellite campus in Galesburg, IL. Although the student population increased throughout the school year, the U of I administration announced that the Galesburg campus would be closed. In response, school members protested and traversed Urbana-Champaign. They proved that they could navigate the campus with minimal interventions. Urbana-Champaign then accepted 14 students with disabilities and made 4 core academic buildings accessible. In the following years, the enrollment of students with disabilities grew. In response, U of I announced that future buildings would be accessible to all students. The students were already researching the best ways to make buildings accessible, with specific investigation into the best slope, material and width of ramps for users with wheelchairs and mobility aids.

“The Ramp that Led to Nowhere”

Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Archives

This research was crucial for the American National Standards Institute. Released in 1961, ANSI A117.1 was the first recognized accessible design standard for the private sector. Public awareness of Accessible Design increased with the passage of the ADA in 1990.

The principles of Accessible Design are not limited to architecture and spatial interventions and are especially applicable to product design as well as the design of technology interface. Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 was amended in 1998 to mandate the Access Board to develop accessibility standards for software, hardware, websites, and other information technology. The World Wide Web Consortium developed the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) in 2008 and was most recently updated in 2018. The WCAG is based on four principles which assert that web content should be perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust.

Framework

Accessible Design is a set of ideas some of which are mandated through legislation in the form of the ADA and WCAG. Accessible Design is frequently applied in architecture as ramps, elevators and doorways, addressing concerns of equity in circulation. The principles of Accessible Design emerged around the middle of the 20th century as many existing buildings in use were not accessible, the logical next step was to research and design interventions. And while these interventions are helpful, without thoughtful integration they give users of varied abilities unequal experiences.

It is crucial to consider all users early in the design process and include architects, consultants and future occupants with disabilities in decision making. Designers should have a basic understanding of the differences in user experiences and know concrete ways in which architecture can improve those experiences.

Case Study/ Context

A comprehensive approach to accessibility is needed to facilitate independence for people of all abilities, which may include areas of architecture, product design and web design, as well as urban planning and transportation. Below are some examples that look at accessible design in practice.

Architecture

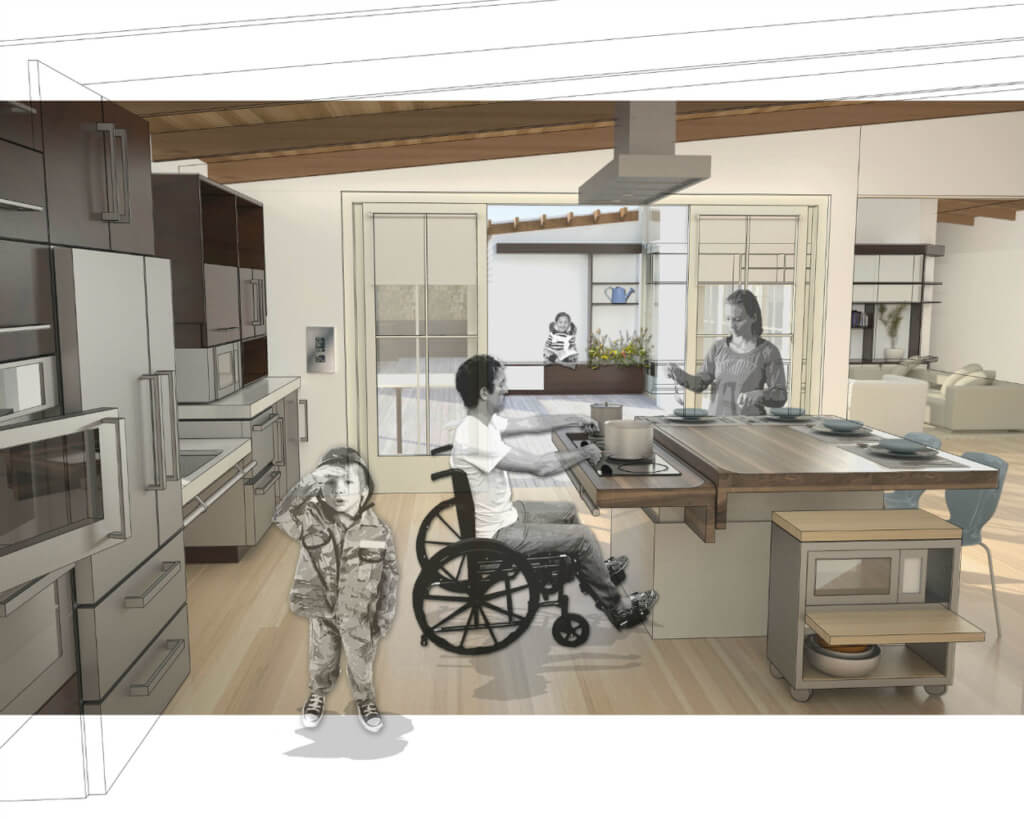

Accessible Military Housing by Michael Graves and IDEO is specifically designed for service members with disabilities and their families. The houses have lowered work surfaces, grab bars and handrails, and wide doorways which allow someone using a wheelchair or mobility aids to live comfortably in their home and have more independence. These homes also address cognitive concerns associated with security, where lowered windowsills and side lights provide ample lines of site for all occupants.

Image courtesy of IDEO

Product Design

ThisAbles by IKEA provides model files for 3D printing that make IKEA products more accessible to people with disabilities. The models address mobility and vision, often relieving users of intricate hand and finger movements. ThisAbles also addresses financial accessibility by making their designs free and downloadable to the public. Below is an example of their product, “Finger Brush,” which helps people who have difficulty using their fingers hold IKEA MALA paintbrushes. It has three loops, one which holds the paintbrush and two which can connect to a user’s pointer and middle finger below the knuckle allowing their fist to remain closed.

Image courtesy of ThisAbles

Web Design & Interfaces

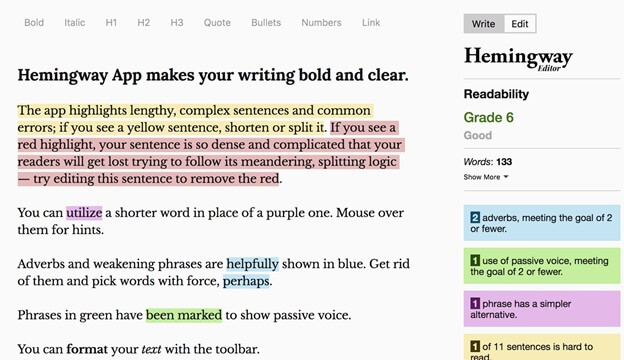

Accessible Design can be translated to Web Design where sites can be edited to improve contrast and simplify wayfinding. Websites can also provide users options to view pages with custom characteristics. The Hemingway App copy edits text through the lens of accessibility. The WCAG recommends content should be written at a “lower secondary education level.” This allows ease of conversion to synthetic speech and helps readers with varying levels of abilities.

Image courtesy of the Hemingway App

Conclusion

Accessible Design is most successful when incorporating safe and standardized principles which make spaces, objects and technology accessible to those with physical disabilities. The strategy has a larger scope than the standards set by the ADA and WCAG. Yet, they all work as additive measures that deviate from a “typical” experience.

References

History of Accessible Facility Design

Gaining Momentum: DRES at the University of Illinois

WCAG 2 Overview

IDEO Work Journal Tools

Case Studies

Accessible Military Housing

Ikea ThisAbles

Hemingway Editor

Previous Posts in this Series

Spatial Equity: Designing Beyond ADA

Spatial Equity: Equitable Design Strategies