At its core the Spatial Equity Research Group is interested in design through the lens of social equity, diversity, and inclusion. This post is the second in a series exploring equitable design standards.

Definition

The Americans with Disabilities Act is a piece of civil rights legislation that protects the rights of people with disabilities by prohibiting discrimination in employment, ensuring access to state and federal services, and regulating public buildings and transportation. Titles II and III were adopted and revised into the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design, which center accessibility in design within a human rights context.

History

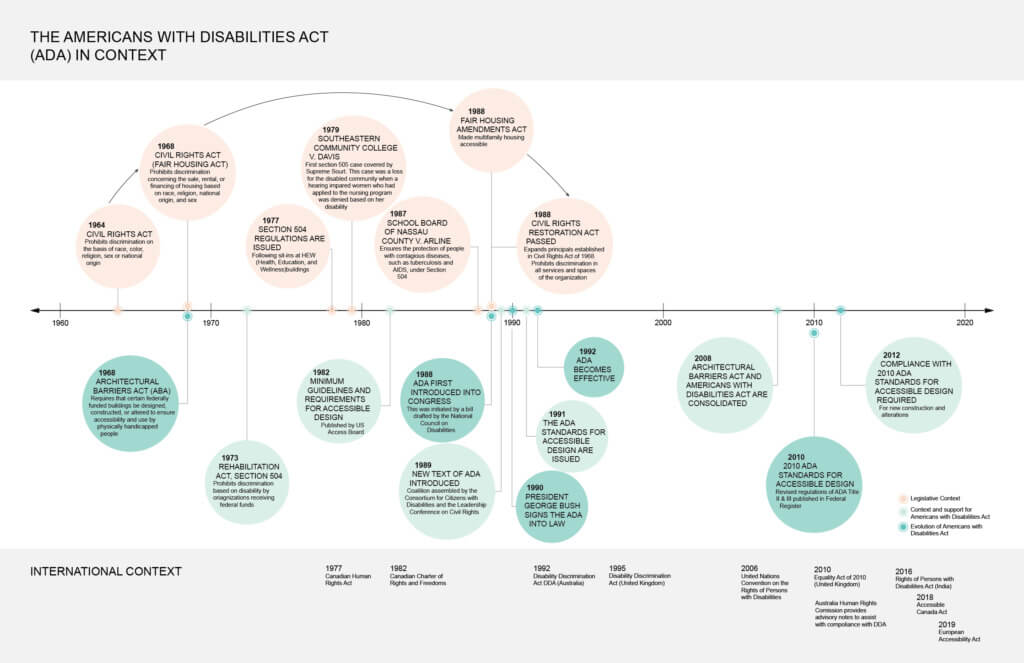

Click for larger view.

The events outlined above would not be possible without the tireless work of thousands of activists, culminating in fierce letter writing campaigns, a national call to write “discrimination diaries,” and many meetings with members of Congress. The testimony of people with disabilities at the joint hearing in September 1988, which first introduced the Americans with Disabilities Act to Congress, and included over 700 supporters, advocates, and members of the disabled community was a turning point in making disability rights a priority for lawmakers. However, at over 30 years old is the ADA enough to continue to guarantee the rights of people with disabilities access to public spaces?

Framework

The Standard for Accessible Design provided by the Americans with Disabilities Act is useful as a foundational tool in regulating the design of public and commercial space for those with almost exclusively physical disabilities. As a national law it is an incredibly powerful tool, the mandate of these spaces confirms and validates those with disabilities in our society. Although the ADA sets a strong foundation for designing for the disabled community its limited scope focuses predominately on physical, visual and auditory impairments. Additionally, the focus is heavily on architectural interiors rather than the broader public space and landscape. In practice this is often used by designers as the desired achievable standard rather than a foundation which can be layered upon with other equitable design strategies to work toward spatial equity. One of the first steps in creating a positive change is to move away from designing toward compliance and start designing after it.

Context

Architects usually understand accessibility through code and the Americans with Disabilities Act. However, these sets of codes have not been integrated with design culture and other user identities. As a result, the ADA is often applied as an additive layer in the form of ramps, handrails, grab bars, etc. rather than being holistically integrated into the design.

One of the more generally known facets of this Design Standard is the inclusion of specifically sloped ramps in spaces that contain a change in elevation. Ramps are crucial in allowing access via wheelchairs and other mobility aids. Ramps can be the primary circulation to or within a space and thoughtfully designed, often taking advantage of the elongated form as an opportunity for a striking visual or material experience. However, there are many examples of ramps being a secondary concern, often split from a stair as a primary entry, resulting in a building explicitly prioritizing one group of users.

Robson Square Steps, photo courtesy Maggie MacPherson/CBC

McCormick Tribune Hall, photo courtesy OMA

A more recent design is to combine ramps and stairs in a wide block, as demonstrated by Rem Koolhaas’ McCormick Tribune Center at the Illinois Institute of Chicago and the Arthur Erickson’s Robson Square Steps in downtown Toronto. The wide circulation block also encourages seating and gathering spaces. Although the steps of the McCormick Tribune Center do have visual striping that differentiate the levels and outline the ramp; however, these meandering ramps are often visually confusing in the context of the stair patterning. In addition, the handrails are limited to the outermost limits of the stair, once again prioritizing the experience of users who can tread the stairs. The offset between the stairs and ramp is dangerous, posing trip and fall risks without the use of handrails going up the ramps.

Lower Sproul Plaza, photo courtesy CMG

Comparatively, the Lower Sproul Plaza at UC Berkley, separates the two, creating two stripes of lush garden ramps separated by stairs. Handrails are used throughout and patinaed metal planters are visually striking against the concrete, creating a clean border for the rise. The stairs and ramps share landings and views to the green space. This particular design is successful in creating a more equitable space, and more beautiful one.

Conclusion

The ADA establishes a strong foundation and guidelines for designing spaces for people with physical disabilities, however it lacks acknowledgement or framework to design for other users. It is not just a civil rights issue, but an equity and inclusion issue. Moving forward is ADA and the code enough to provide all users with the same equitable experience? As designers, what spatial design strategy can we use and promote that holistically includes ADA in the process and challenges its limited scope?

We will explore these questions and others in future posts in the series.

References

The History of ADA

About the ABA Guide

ADA.gov

2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design

Easterseals

OTHER POSTS IN THIS SERIES

Equitable Design Strategies