Recently, PAYETTE’s fabrication team coordinated an MGR|MGR event at the Dassault Systemes campus in Waltham. Attendees from local architecture firms and related industries enjoyed a discussion led by 3DS Vice President of Strategy, Patrick Mays, AIA as well as a tour of the 3D Experience Lab.

Patrick challenged conventional models of architectural practice, calling for alliances between architects and advanced manufacturing professionals, and prompted the group with a simple question: Why aren’t there any publicly traded architecture firms? Many of the project management consultancies and engineering service bureaus who hold prominent stances on the index rely extensively on coordinated expertise in building systems and architectural planning. In fact, some of these same service bureaus make only a tenth of the revenue of the largest architecture firms. So why is it that the key architectural collaborators of these companies do not share the same status as their publicly-traded counterparts? If it is not a problem of an inadequately scalable business model, then why abstain from the stock exchange?

By eschewing potential revenue streams, architects are leaving money on the table. Consider the business models of the four largest elevator companies in the United States (Otis, ThyssenKrupp, Kone, & Schindler). An average of 10% of each company’s annual revenue stems from sale and installation of elevators, whereas 35% of profits are generated through elevator maintenance, mechanical upgrades, and repairs (the remaining profits come from investments, consulting, and a myriad of other pedestrian circulation products such as escalators and moving walkways). Simply said: even if there is a down quarter in sales, 30-year maintenance contracts will ensure a steady cash flow for the organization. If maintenance contracts are more than three times as profitable as the sale of the products themselves, one can infer that the priorities of shareholders and senior leadership primarily concern continuing ongoing relationships with the client long after the product is delivered. How can this business model challenge or inform the way we think about architectural deliverables? Such a partnership between architect and client would be characterized by providing ongoing design and planning services long after the project completes. Patrick argues that many building systems could benefit from this model.

For example, recent experiments in intermodular residential construction have captured much media attention and public fascination. In response, several companies have been founded upon a value proposition to provide architects and designers with a platform to customize modular kitchen and bathroom units that can be installed quickly and with relative ease. Before fabrication commences, all these modules must be fitted within the constraints of flatbed trucks, and carefully consider the method by which the unit will be deployed into the job-site. Naturally, a building optimized to receive such units could afford periodic upgrades in the same way one would upgrade one’s washing machine after it exceeds its margin of planned or perceived obsolescence.

Additionally, this model could prove useful in healthcare design, where spaces are often configured to support specific procedures and equipment. How could a space be designed to anticipate advances in technology or changes in medical methodology so that the space could be easily “upgraded”? With careful implementation, this model could positively benefit a healthcare institution’s longevity while remaining agile enough to continually support evolving patients’ needs.

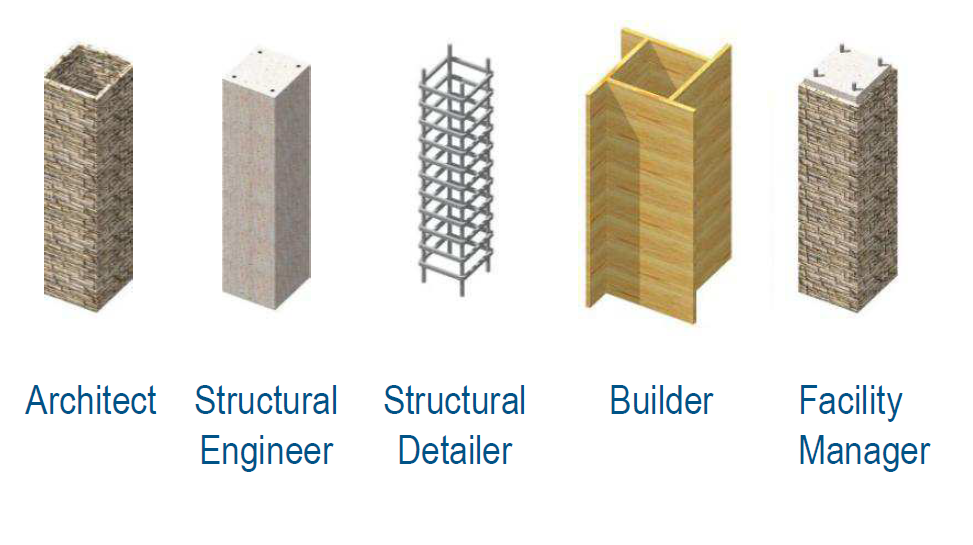

Similarly, designing for shop-fabrication can streamline construction and control risk. Uncertain field conditions and job-sites congested with trade unions working on top of one another often result in time delays and cost overruns. To decrease the possibility of mistakes on the job site, many areas of the building materials industry have re-structured to specialize in the fabrication of integrated mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems optimized for quick installation. When building elements or systems are outsourced to be fabricated offsite at a specialized facility, they will abide by a stricter quality control standard. Designing pre-fabricated elements for delivery can reduce job-site accidents, injuries, and uncertainties. Successful execution of this model relies upon interdisciplinary collaboration to attain design intent within the parameters of efficient production.

Patrick emphasizes that as design and planning processes continue to become practiced on optimized Project-Lifecycle-Management platforms, the role of architects must evolve to serve as the custodians of logistics for all facets of project management. In the 21st century, these new responsibilities often translate to a heightened effort to conserve materials. The construction industry fronts frequent criticism for disposing an average of 30% of building materials ordered for any given project. Even LEED-certified buildings which are designed to be efficient throughout their occupied lifetime, do not necessarily have to comply with any strict waste quotas during construction. Whether this waste stems from sudden design changes, trial and error processing, or job-site inefficiencies, significant reductions could be achieved with comprehensive planning, improved training, and process simulations. This is the crux of Patrick’s presentation ¬– architects today stand on the precipice of a tremendous opportunity to interface with alternate business models and automation technology in order to optimize their architectural practice and expand the lifecycle planning of any project’s scope. Heightened efficiency within a firm creates space to prioritize lean construction without sacrificing profitability. Patrick’s manifesto is ambitious and calls upon architects to lead a movement of lean practitioners. To that end, anyone seeking to participate in this movement must reflect upon the following questions:

-From a business management perspective, how much additional attention can be paid to lean efforts before sacrificing profitability?

-If the margins are too thin, how can the entire business model be re-envisioned to support lean practices?

-From a leadership perspective, how can one persuade professionals across trades to practice lean construction?

As 62% of emerging lean practitioners currently find the movement highly inefficient, these outstanding critical questions are valid.

Nonetheless, the combined resources between automation professionals and architects promise limitless potential to improve the execution of deliverable systems and services. Ultimately, to merge innovation and profits with social responsibility is the Holy Grail of ethical enterprise.