PAYETTE recently contributed to the Building Green feature, “Work Globally, Design Locally” exploring how green design is sustaining regional diversity. The article highlights our Aga Khan University Hospital as an early exemplar as PAYETTE Associate Principal Mark Careaga gives insight into the design of the project.

Stop copying the West.

That was the message of a 2016 workshop in Kenya organized by UN-Habitat, where Musau Kimeu called on African developers and architects to design buildings suited to their climate.

“We must pursue sustainable building design strategies to construct buildings that have exemplary humane qualities and that resonate well with the locale,” he said. (Kimeu, who is chair of the University of Nairobi’s Department of Architecture and Building Science, was quoted in the Rwandan newspaper The New Times.)

For the practitioners we spoke with, the priority of regionally appropriate design was always explicit (although the degree to which their clients shared the priority varied), and the examples in the following discussions suggest that it meshes with sustainability seamlessly and flexibly throughout the design process, in the final work product, and at a range of scales.

Pioneering Critical Regionalism: PAYETTE in Pakistan

An early exemplar of critical regionalism, pre-dating Frampton’s essay, is the Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH) complex in Karachi, Pakistan, designed by PAYETTE. Commissioned in the early 1970s and completed in 1985, AKUH originally housed a million square feet of hospital, academic, residential, and service functions. Subsequent expansions doubled its size. The AKUH “embodies the idea that true sustainability lies at the intersection of culture and climate,” according to PAYETTE’s submission for the 2016 ACHA Legacy Award (for which the project was short-listed).

To help PAYETTE’s design team understand the project’s cultural context, the Aga Khan arranged for them to tour major cities and sites from the history of Islamic architecture. Travelling to Spain, North Africa, Iran, and South Asia, the team studied patterns of spatial organization and inhabitation, uses of materials and ornament, and hierarchies of architectural forms, tectonics, and spaces, which the project interprets without imitating.

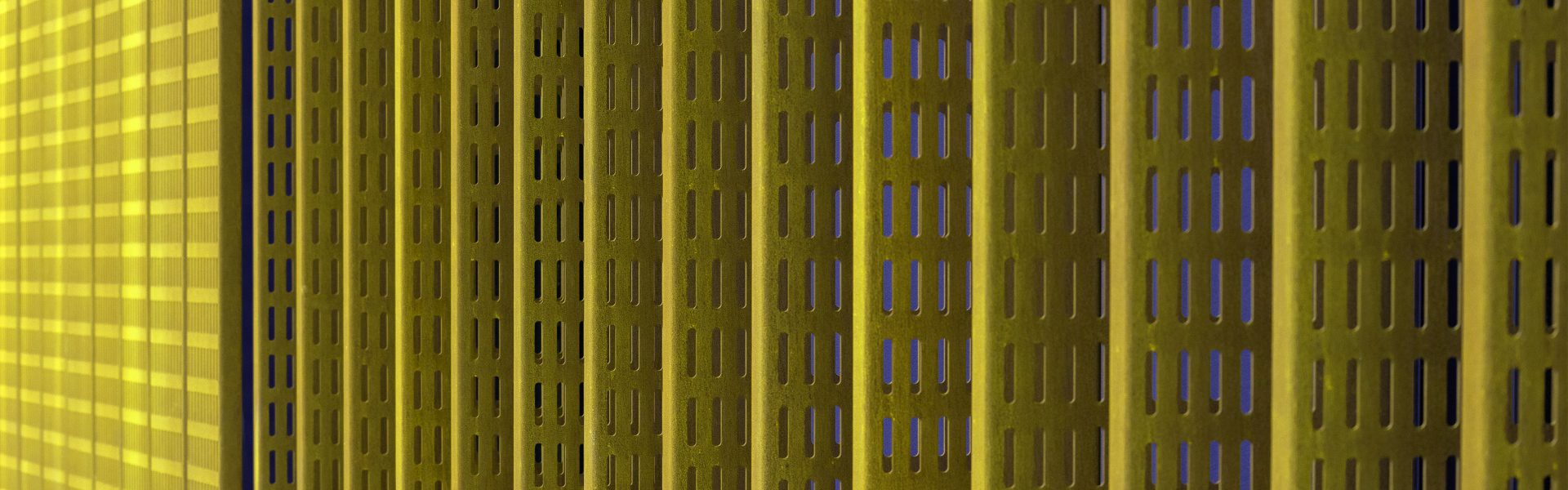

“You won’t see a pointed arch anywhere in the complex,” says Mark Careaga, AIA, an associate principal at PAYETTE. Main entrances to the complex reference the traditional portals of Islamic cities, for example, but instead of mimicking the traditional ornate muqarnas (a style of honeycombed dome) of Islamic architecture in the transition from monumental-scale to human-scale openings, AKUH portals make the move with marble-lined inclined planes.

Climatically, Karachi varies between hot and dry, and hot and humid, so protection from the sun became a primary design driver. Combining cultural and climatic response, the complex consists of buildings and courtyards laid out on a grid oriented to the principal compass directions. Window openings respond to orientation, using deep recesses and splayed walls to minimize sun penetration. Teak mashrabiya screens provide additional protection while reducing glare for occupant

Read the full BuildingGreen article. Please note, a subscription is required to access the article.