Design Week is an annual PAYETTE tradition when we as a firm collectively explore projects we have worked on during the previous twelve months. Over the past few weeks we have recapped the presentations given by our colleagues.

PAYETTE projects are notorious for grappling with complex site constraints. These constraints inform our buildings’ massing, orientation and even program. However, today we will dive deep into how these constraints also frequently produce one-of-a-kind, responsive façade solutions.

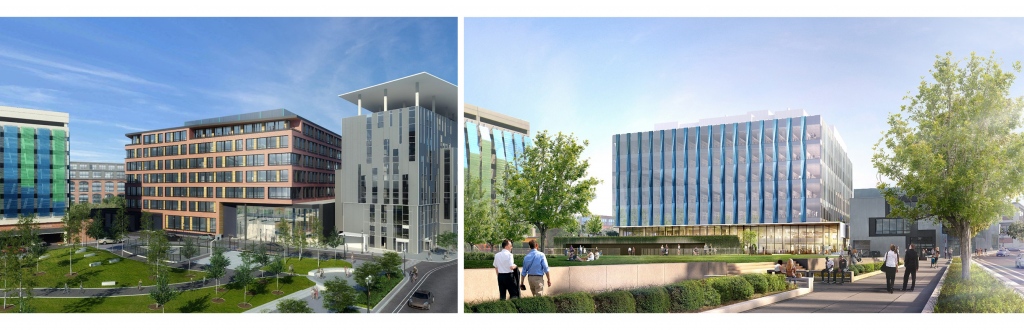

105 West is 290,000 GSF and primarily a lab and office building with six stories, a penthouse, and below-grade parking and athletic facilities. While a new construction project, PAYETTE inherited an already city-approved building design for the project. However, the prior design was for an office space and the building needed to be redesigned for labs.

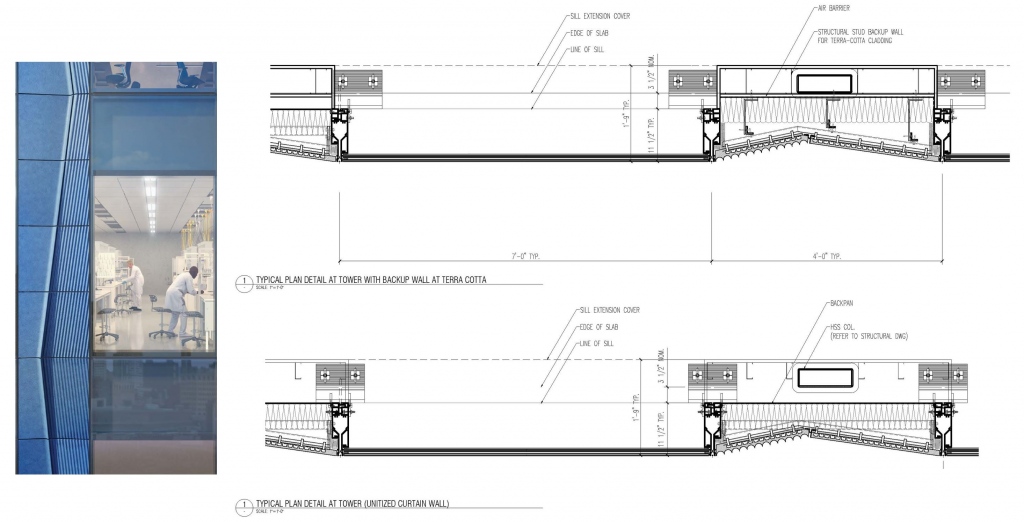

Unsurprisingly, the office-to-lab conversion required drastic changes to floor-to-floor heights and the use of every square inch on the site. Thus, the design team hid these height changes behind a vertically oriented façade and pushed the project’s glazing as close to the site boundary as possible. And upon close inspection, one can even see that the glazing extends past the sinuous terracotta panels 105 West is known for.

The resultant façade is relentlessly regular as it wraps the building, and its more muted and canvas-like appearance better blends into the adjacent artsy neighborhood compared to the original BPDA-approved design.

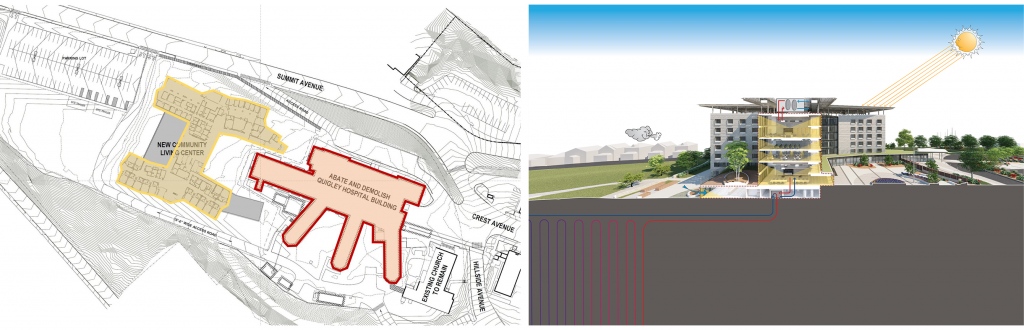

If 105 West’s façade can be described as convex and ballooning, The Chelsea Veterans’ Home has a façade that is concave and accommodating. This long-term care facility sits atop Chelsea’s Powder Horn Hill with an undoubtedly attractive site; however, the inability to immediately demolish the existing soldier’s home produced a myriad of constraints for the new building’s façade.

So, despite being the project being primed to take advantage of panoramic, 360-degree views and daylight from every angle, the project team had to work out how to accommodate a functioning Veterans’ Home that cut deeply into the site. Ultimately, the proposed solution split the building into wings which provided necessary setbacks for construction and gave the new façade the appearance of cradling the existing one. Also worthy of note is how the building’s “butterfly” massing and façade aid in the project’s performance-based design goals. Viewable from miles away, the project’s rooftop solar array harnesses solar energy while also serving as a visible symbol for less-visible sustainability efforts like the building’s high-performance envelope, elegant brick façade (in lieu of abundant glazing), and geothermal heating and cooling system.

Wesleyan University

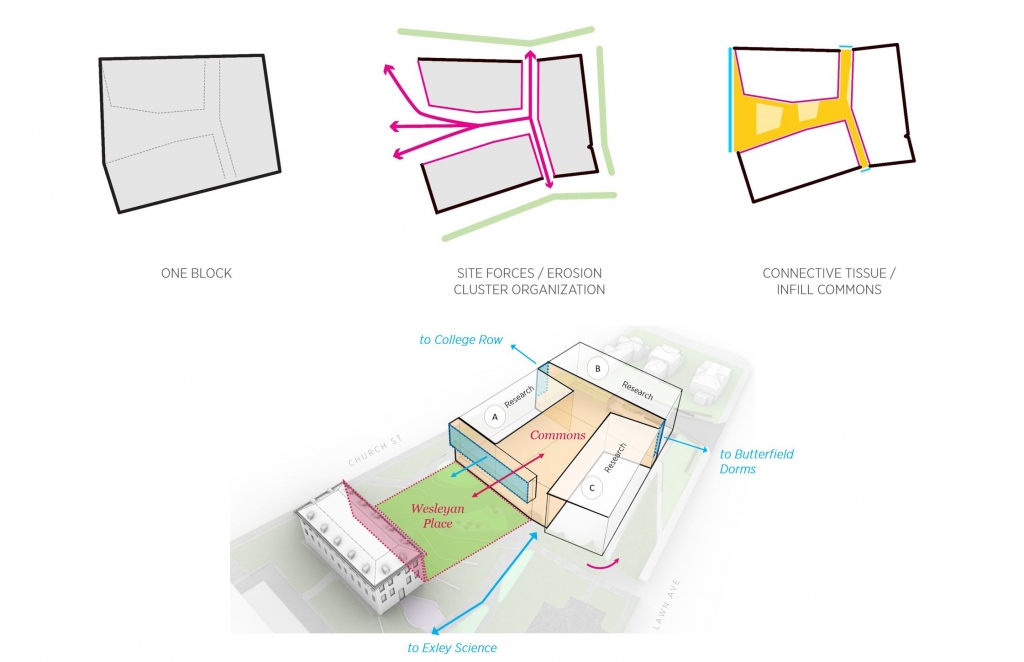

The next project is the Molecular and Life Sciences Building at Wesleyan University. And in contrast to the previous projects, it is not the first in a series of developments or a replacement of an existing building, rather it is a strategic addition within an already existing science precinct. Wesleyan’s science precinct has two complex constraints: 1) the traditional campus architecture makes fitting in a contemporary design more difficult, and 2) the grade difference between proposed and existing is approximately 30 feet. Therefore, PAYETTE was tasked with not only designing a building but also a connecting landscape.

The landscape design yields to existing campus forces and employs sloped walks rather than ramps and stairs to navigate the grade change. This way, diverse users can traverse as much of the landscape as possible without encountering less-welcoming design elements, like railings. Furthermore, the façade design of the new life sciences building responds to campus forces by aligning interior common spaces with exterior desire lines and using larger glazing elements to strengthen the connection between inside and out. The rest of the project’s façade is made of stone to not draw unwanted attention while also allowing research “clusters” to be easily identifiable from the exterior.

Harvard Medical School Renovation

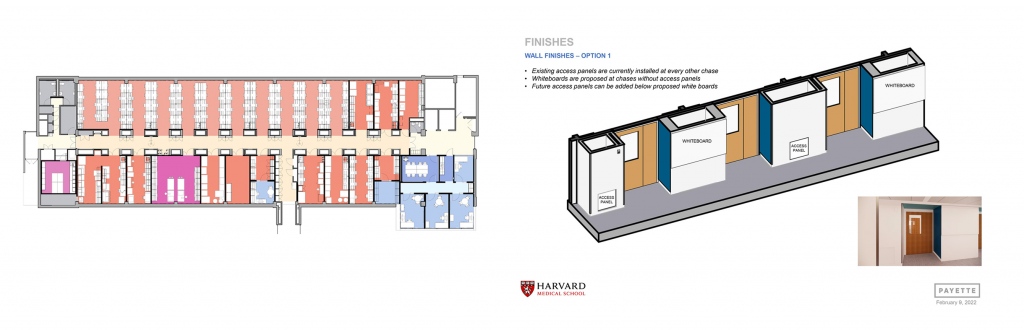

The last project is the Seeley G. Mudd (SGM) renovation at Harvard Medical School, and in this project, the complex constraints and responsive façades are all interior. Located at the Longwood Medical Campus, the renovation includes two lab floors within a six-story building. This is one of several lab fit-out projects with the goal of unifying the campus experience. Currently, the campus is extremely piecemeal design-wise. Even within SGM, the interior architecture can vary floor-by-floor or hallway-by-hallway.

The two lab floors in question (floors 3 and 5) are dated and have minimal identifying features beside a militant cadence of mechanical shafts that line the corridors in plan. After much experimentation, accent paint was chosen as a minimal and cost-effective solution to help unify the corridors and provide hints of wayfinding. Moreover, much needed whiteboards were placed on chase walls outside of each lab and positioned to not obstruct current and future access panels. Even in renovation projects, it critical for designs to respond to future needs in addition to current ones.

At PAYETTE, we pride ourselves on tackling projects with particularly difficult constraints. Furthermore, our expertise is not simply in designing labs and hospitals, rather it is in delivering creatively elegant and responsive solutions.