With the public opening of the new Harvard Art Museums just around the corner this weekend, we’d like to look behind the scenes regarding a few distinct elements of the museums. Perhaps you’ve already heard about the careful integration of old and new in the project. What may be less familiar are some of the one-of-a-kind details of the historic building. We strove to preserve and unearth these hidden gems for enjoyment by future generations. Today we’re looking at the preservation of the frescoes and the Naumburg Room.

Frescoes

A series of frescoes, emblematic of the museum’s pedagogical mission, existed in the old building. These were created in the 1930s to teach students about fresco techniques. Three frescoes have been retained—by different means—for display in the new facility.

End of the World, located within the Art Study Center on Level 4, was protected in place. We carefully considered this painting in the design of the seminar room that contains it. The fresco surface was safeguarded with a chemical protectant, then covered during construction. A new glass enclosure was designed for it so it would not interrupt the thermally improved envelope.

A second fresco, Structure, was structurally supported, cut out of the existing masonry wall, and then moved a short distance from its previous location on the lower level to a new resting place on the same floor. Due to the extraordinary weight of the masonry, the path to the new location was designed with the movement of the fresco in mind. The relocated fresco has been detailed to celebrate its history, with the cut ends of the wall exposed.

As with Structure, Hunger March, by artists Lewis Rubenstein and Rico Lebrun, the team stabilized and cut out the fresco from its original location on the top floor of the building. However, while the tower crane was in place, it was lifted out of the building for storage offsite during construction. Later, the fresco was rigged into the first floor Social Realism gallery, where it will now be on display, integrated into the collections.

Naumburg Room

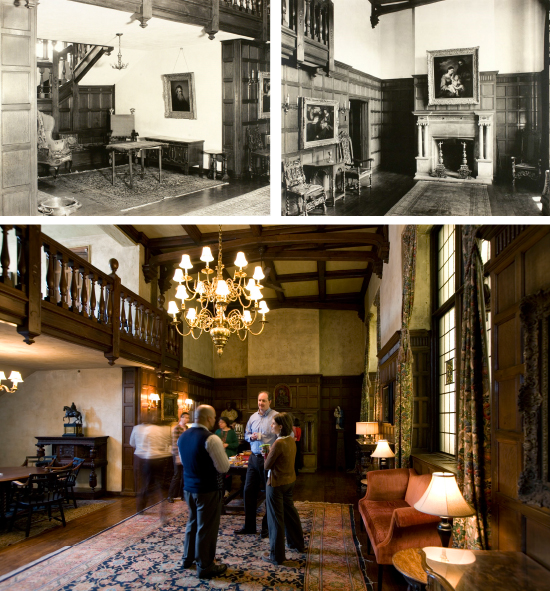

Perhaps better known to long-time visitors than the frescoes, (originally concealed in back-of-house spaces) is the Naumburg Room, a double-height Jacobean hall that previously occupied a purpose-built 1932 addition to the 1927 building. The room came from the penthouse apartment that Nettie and Aaron Naumburg shared in New York’s Hotel des Artistes; Nettie bequeathed the room and all its contents to the Fogg Museum.

Early in the design process, the decision was made to demolish all post-1927 additions to the original building, and so the search began for an appropriate new location for the Naumburg Room. We identified the south wing of the original building as the most suitable location. However, to fit there, the room needed to be slightly modified. This was no simple task, as the Naumburg Room is listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places and its use and care are governed by the terms of the original bequest. Happily, the bequest proved less restrictive than anticipated: its primary stipulation is that the room be available as a gathering space for contemplation and discussion of art. To this end, the room’s new location, adjacent to both curatorial offices and galleries, invites regular use by the museums’ director and staff, as well as by other members of the Harvard community and special guests.

The finished Naumburg Room is a beautiful fusion of old and new. Unlike the rest of the new facility, required upgrades have been camouflaged in this space, to match the historic character rather than to call attention to themselves. The original wood floor could not be salvaged (its underlayment contained asbestos), but it was replicated beautifully using reclaimed lumber. Doors were meticulously modified to meet functional requirements while still using the original wood panels, and hardware was repurposed wherever possible.

The room’s engineering systems were completely modernized. The original grilles under the windows are now used to deliver supply air; return air diffusers are carefully located so as not to interfere with the detailed wood ceiling ornament, using window heads in most cases. AV equipment has been tucked into a previously unused closet. A new projection screen is hidden within a wooden ceiling beam, masterfully modified to allow the screen to appear or disappear as needed. All original light fixtures were rewired and restored.

As in the previous incarnation of the Naumburg Room, stained glass will be on display within the windows—which are, in fact, not true openings to the exterior, but rather illuminated shadow boxes. The windows were painstakingly rebuilt, using hand-blown art glass, to complement the works of art they showcase. The lighting of the window cavities, complicated by their shallow depth, was studied in detail through a series of mockups of the LED fixtures, cabinetry and glass components.

The result is a thoroughly modern room that still feels like a step back in time and remains a place for contemplation and conversation.

Photos in slideshow depict the restoration process for Hunger March.