(The WHAT of psychosocial research in architecture)

This is the third post in a series considering the role of psychological research within the context of an architectural practice. The goal of this series is to provide answers to six key questions, namely, the why, what, who, when, how and where, of design focused psychological research.

In my previous post we looked at why design focused psychosocial research matters within the architectural practice. In this post we will discuss the “what,” which is the nature of this type of research by referring to five primary characteristics. A discussion regarding the nature of this research differs from a discussion on appropriate methodologies. While this post addresses the “what,” a future post will address the “how.”

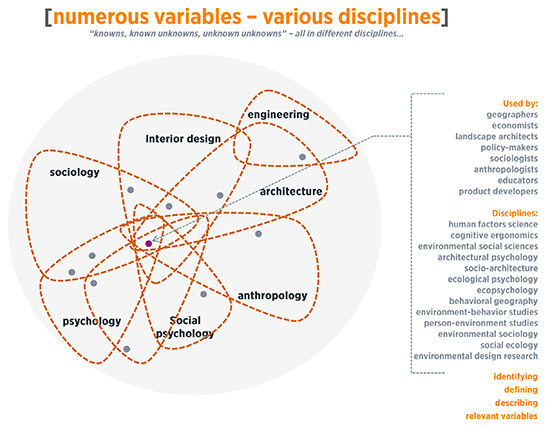

It is important to note, at the onset of this discussion that, psychosocial research, as it relates to the designed environment, can be especially complicated. This is primarily due to the number of variables present in the designed environment and the fact that some are difficult to define, and almost impossible to measure. Adding to the complexity is the dynamic relationship between variables and that these interact with each other within the context of a larger equally dynamic social and cultural environment. However, many of these challenges can be managed by setting realistic study goals based on a clear understanding of the nature and limitations of this type of research. In an attempt to better define this field of research at least five aspects regarding its nature should be emphasized:

Interdisciplinary: By its very nature psychosocial research in the architectural practice needs to be interdisciplinary. To accurately describe the variables and their relationships requires input from a number of different disciplines, none of which the architect in innately familiar with. On this point reference should be made to well-established research disciplines such as social and environmental psychology, cognitive sciences, anthropology and sociology. However, given the contribution of various design disciplines to the designed environment, input from the various design disciplines; interior design, lighting design, industrial and furniture design is also required. Architectural practice is by nature a cooperative, multi-disciplinary endeavor. Psychosocial research in architecture should build on this multi-disciplinary foundation, crossing over, where needed, into the interdisciplinary.

Conceptually delineated: Given the interdisciplinary nature of this research, a designer hoping to engage in psychosocial research should develop a general understanding of the key concepts of related disciplines. There exists, in architectural design, a relative freedom to appropriate, and sometimes misappropriate words and concepts to describe a particular design idea. While this is useful within the context of a specific project, these terms are not usually used as part of a larger academic discussion. However, as designers engage in interdisciplinary research there should be a clear understanding that a larger research discussion, extending beyond the boundaries of architecture, depends on a shared understanding of formally defined, and acknowledged, terms. Designers wanting to engage with research in this domain should do their due diligence to become familiar with the ‘industry jargon’ of related disciplines.

Rigorous (but not necessarily experimental): Related to the previous point is the requirement that psychosocial research should have an intentional rigor to the definition of concepts and the selected methodology. This is especially true should the designer be interested in presenting or publishing the results of the research. Given the specific requirements for peer reviewed research, the intent to publish in an accredited academic journal should be considered at the onset of the study. It is worthwhile to point out that although some firms might be able to pursue studies of a more experimental nature, the requirements of experimental research are such that, in most cases, this will be the exception rather than the rule. It is highly recommended that architects, wishing to engage in more specialized forms of research do so in collaboration with academic researchers. These collaborations, although difficult to establish and manage, holds immense potential for both researcher and practitioner for developing new methodologies and attaining results with practical applications.

Methodologically flexible: Although psychosocial research should be rigorous there needs to exist flexibility in terms of the various methodologies available to the designer. Considering that this field of research is still developing, the architect’s research toolbox should contain methodologies from a number of different disciplines. More importantly, given the unique challenges and varying physical and social contexts of the designed environment, the creation of new methodologies based on the research question and available resources should remain a possibility. Various methodologies, many which have been used successfully in design firms, will be described in a future post.

Outcomes based: Just as material research in architecture is directly focused on specific outcomes related to an actual building, psychosocial research in architecture should be aimed at addressing specific questions aimed at ultimately generating specific design solutions. Research, for the sake of research, is questionable within a real-world context of billable hours and time based project delivery. Design focused psychosocial research is not unlike design focused material research where, for example, research regarding the thermal conductivity of an insulated glass unit is not primarily for the sake of better understanding thermal conductivity, but rather to better understand the contribution of the glass unit as part of a larger facade assembly, to the overall building performance and occupant comfort.

Although similarities exist between design focused psychosocial research and traditional academic research disciplines, there are significant differences. A clear understanding of these differences is essential when considering the unique challenges of this type of research. At times these differences will require the development of new outcome based methodologies. The degree to which firms will develop their own methodologies will depend on the experience and objectives of the designers involved.

In the next post we will discuss the “who” of design focused psychosocial research by considering the characteristics and requirements of the various individuals and organizations involved with this form of research.

Related:

An Introduction to Psychological Research in Architectural Practice

Why does psychological research in architectural practice matter?

Considering psychosocial research as a part of architectural practice