This is the third post in a series considering the role of psychological research within the context of an architectural practice. The goal of this series is to provide answers to six key questions, namely, the why, what, who, when, how and where, of design focused psychological research.

In this post we continue to look at the “why” of psychological research in architectural practice by asking whether this type of research should matter to architects and designers and if so, what contribution it can make to the practice of architecture.

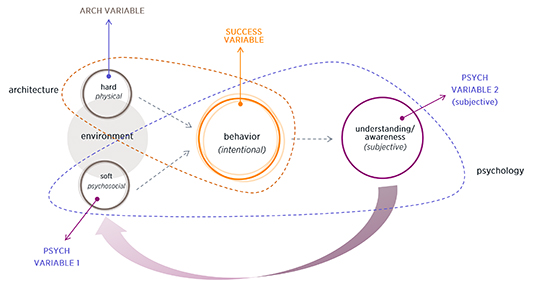

While the potential benefit of psychosocial research for building owners and users were discussed in the previous post, the benefits to architects are not as clear. This is especially true considering that many very successful buildings have been designed in the past without architects consulting with behavioral scientists, or analyzing design decisions based on the psychosocial implications, but rather by relying on experience and intuition. While there is no substitute for design experience – the understanding a designer develops over many years of practice – designers rarely create documents that summarize their experience. Similarly, the vast majority of architectural research takes place during the design process, with very little follow-up after a project is completed. In most cases follow-up only occurs once a building deficiency is discovered and then primarily for the purposes of litigation. While the physical success or failure of a building is evident, the psychosocial success or failure is not. In order to better understand this aspect of building performance, and to document current and future performance, an intentional assessment, as part of a larger research effort, is required.

Psychosocial research can benefit an architectural practice in three ways by:

- Helping architects formalize design experience

- Displaying expertise and building credibility

- Improving the quality of the final design product

Irrespective of a designer’s architectural or research agenda, there exists a generally accepted assumption that the performance of a space, whether physical or psychosocial, matters. Architecture is not purely art and it is not sculpture. It shapes the environment in ways that go beyond the purely aesthetic and evokes a psychological and behavioral response from occupants. Is this not therefore the responsibility of the designer to, at the very least, attempt to better understand the influences of our work given that users respond to it, in most cases without choice, on a daily basis?

If design success is measured by how effectively a space addresses both the physical and psychosocial objectives of the client – objectives mediated and interpreted by the designer – it is certain that, as designers, we need to have a basic understanding of how these objectives are addressed through our designs. Many firms have found writing white papers a very helpful method to formalize the collective experience. This does not only allow for the development of the designer’s own understanding, but it also assists in the transfer of information to designers starting off their careers in an established practice. Even in cases where ‘rules of thumb’ exist, the dynamic nature of the design environment requires a periodic reconsideration and testing of these rules. Psychosocial research is one way to test the assumptions behind the rules.

A practice that can demonstrate a documented awareness of the impact of its design decisions on building performance, builds credibility. This awareness can be obtained through an intentional and systematic process of examination – that is, a basic research process. The process of examination does not only reveal potential shortcomings in the design process, it also allows firms to develop and document its expertise in specific programs or building types.One example of how psychosocial research can assist architects in developing their expertise relates to the energy consumption in buildings. Since the energy performance of buildings is influenced, to a large degree, by the thermal comfort of occupants, and thermal comfort is essentially a subjective evaluation, the growing interest in the design of energy efficient, and high performance buildings, suggests a number of promising intersections between psychosocial research and technical building system research.

The conversation about the psychosocial performance of designed spaces is intensifying, not much differently from the way the sustainability conversation of approximately 15 years ago intensified. The question for architects is not whether the conversation will continue, it is whether we will be willing to take part in it, perhaps even take the lead in it, by addressing it through our practices. If we do not, it will simply be a matter of time before other voices will lead the conversation.

Related:

An Introduction to Psychological Research in Architectural Practice

Why does psychological research in architectural practice matter?