This is the ninth post in a series considering the role of psychological research within the context of an architectural practice. The goal of this series is to provide answers to six key questions, namely, the why, what, who, when, how and where, of design focused psychological research.

In the previous post, the “when” of design focused psycho-social research was discussed. This post will address the “how” of psycho-social research by considering the disciplinary fields and methodologies most often associated with this type of research.

A discussion of this nature needs to acknowledge, as a starting point, that the theoretical underpinnings of design focused psycho-social research originate in a number of different disciplines, and primarily so in the social sciences. As described in a previous post design focused psycho-social research is essentially an interdisciplinary undertaking. Given the context of this series – the architectural practice – it is important to understand that this type of research will however differ from ‘basic’ research undertaken in the academic disciplines. The specific methodologies will therefore also be different.

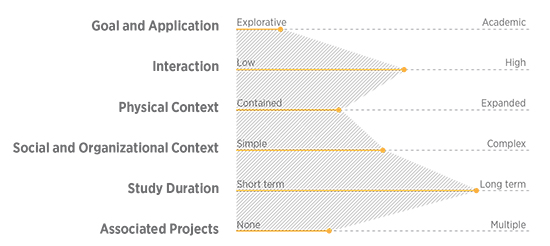

The discussion regarding specific research methods will be delayed until a future post, since it is necessary to first consider the factors that influence a decision to use a specific research method. Although there is a wide range of factors that feed into the design of a specific study, in this discussion the focus will be on six key aspects to consider when deciding on the most appropriate method or instrument for a specific study. These aspects are: Goals and application, level of interaction, physical context, social and organizational context, duration of study and associated research projects.

Goal and application of research: One of the most important considerations when determining the appropriate research method or instrument is the intended use for the research findings. For simple explorative studies the results may have little practical application. This is particularly true when new methods or instruments are developed and tested. However, where the research project is part of a formal study, or formal publication is anticipated care should be taken when deciding on a method. Concepts such as validity and reliability of the process and instruments are crucial when considering formal studies.

Level of interaction: Given that design focused psycho-social research often involves building users, it is important to define what level of engagement there would be between the researcher and the users and how the interaction will be scheduled and facilitated. While this may sound like an obvious consideration, projects where this aspect is not considered well in advance of study development can easily end up in a situation where data collection is hampered due to privacy concerns or deficiencies in communication. This is true for both direct methods, such as interviews, surveys and focus groups as well as indirect methods such as time-motion studies or independent observation and shadowing.

Physical context: Since design projects range in scale it is reasonable to assume that the physical context of research projects will also range in scale. Studies focused on smaller designed environments, such as a single lounge, laboratory or classroom will require a different approach than, for example, a study considering behavior in an urban context or on a campus. Studies of the larger physical environment may require the consideration of more technically complex methods or adjustments to the frequency and extend of data collection.

Social and organizational context: Considering that many design focused research projects focus on environments which are actively occupied, the nature of the social and organizational context of an environment should carefully be considered. One of the most rudimentary concerns, well documented in the social sciences is the observer effect, or similarly the Hawthorne effect, where subjects adjust their behavior due to the presence of the researcher. Additional items related to the social and organizational context are protecting the privacy of occupants and understanding institutional policies relating to photography and video recording. Whatever the context, the researcher should be aware of the direct and indirect effect the study might have on the users of a specific environment when designing the study.

Duration of study: The duration of a study can vary from a couple of hours to several years and therefore has a significant influence on the method and type of instrument used. Manually recording data may be a viable solution for short term explorative studies, but where standard assessments need to be repeated by different individuals over an extended period of time, additional thought should be given to the methods of collection, coding, processing and storage of data, and the value of one instrument or method over another.

Associated research projects: In firms where a robust research agenda exists it is not unusual to have team members engage in a number of different research projects. In these cases it is useful to consider the degree to which these studies can enhance each other. This is especially true in cases where the studies initially seem to be unrelated, e.g. a study on thermal comfort vs. a study of lounge spaces. When considering potential methodologies for seemingly unrelated studies, potential efficiencies and advantages should be identified. Operational efficiencies might include the sharing of travel expenses, combined data collection or shared responsibility for existing condition documentation. Advantages may include the expansion of the study to considering the relationship between lounge utilization and thermal comfort, for example. This is particularly true for studies where one study considers easily measurable phenomenon such as temperature, energy use, light and noise levels, while another study considers defined individual or social behavior.

With a better understanding of the nature of the proposed research project, the researcher can start considering the various methods. The next post will describe a number of tools available in the architect’s toolbox for use in the execution of design focused psycho-social research.

Related

An Introduction to Psychological Research in Architectural Practice

Why does psychological research in architectural practice matter?

Considering psychosocial research as a part of architectural practice

5 Points on the Nature of Psychosocial Research in Architecture

WHO: What to ask when assembling a psychosocial research team

WHO: Psychological research in architecture, Part 2

WHO: Psychological research in architecture, Part 3

The WHEN of psychological research in architecture