Credit: SENSEable City Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

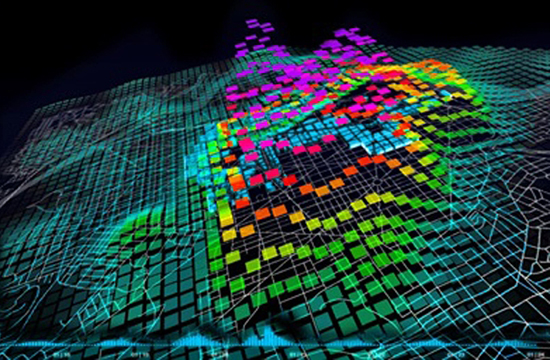

This fall at ABX I attended an intriguing presentation called “Designing Urban Technologies,” hosted by researchers from the MIT SENSEable City Lab. The lab focuses on the ways in which data collection through sensors or hand-held electronics are “allowing a new approach to the study of the built environment.” The talk was broken up into shorter discussions focused on each researcher’s projects, and was followed by a panel discussion of the issues surrounding data collection and sharing, as well as the future of our built environment.

According to SENSEable, the world is now producing 5,000,000,000 GB of data every 36 hours, which is equivalent to the amount of data that has been produced from the beginning of humanity until 2003. With the help of websites and applications like Yelp, Facebook, Twitter, etc. it has become much easier to access a lot of this data to answer questions like, where is gas being purchased in a specific city, within a specific time frame? Or, where are the food “deserts” within a city that might indicate where the next grocery store should be planned? Looking at a smaller scale, the researchers are also asking questions such as, who turns the lights on and off in a building? Or, how is the HVAC system reacting to environment?

The most interesting studies of data use are exploring how to create efficiency in the urban landscape and the built environment. Two particular examples shared in the presentation explored increased taxi utilization in New York City, without additional spending (HubCab), and using drones to test and track levels of harmful bacteria in local bodies of water (Waterfly).

The idea behind HubCab is to track taxi-use data like destination, pick up location and time of day to understand the travel habits of New Yorkers, with the intention of encouraging ride sharing. While this seems like a simple idea on the surface, taxi ride sharing also has far-reaching benefits. SENSEable’s research shows that the number of taxi trips in NY could be reduced by 40%, which accounts for significant fare savings, as well as reduced CO2 emissions.

SENSEable’s research for Waterfly started with a competition entry for “The UAE Drones for Good Award” that proposed using a swarm of drones, equipped with data-gathering sensors, to “scan and probe lakes and rivers for emerging pollutants and threats.” The idea also aspires to provide the public with open-source data sets that may spark more interest in and research of our environmental challenges.

The ability to glean data from a myriad of ideas, activities and habits at such a fast pace, and in such large quantities, also raises questions of access, efficiency and reliability that designers have never asked or dealt with before. What is most interesting about data collection (active and passive), and these ideas as they relate to design, is the possibility of conclusion and future adaptation in our design solutions. What was once beyond the grasp of feasible exploration, due to time or extent, is becoming seemingly commonplace. Answers to our once theoretical inquiries about how the city interacts with our buildings, or how natural environment affects structure and orientation continue to give designers the opportunity to thoughtfully react to the people and places for which we design, now with tangible data.