I love working in Revit, from schematic to CA. But sometimes you need a little more than a Revit model to explain where you’re going. Something detailed but informal, something where you can emphasize some things and just hint at others, something … hand drawn?

During my recent work on cleanrooms I’ve made a lot of sketches to explain the projects. The simpler drawings were freehanded from scratch. For others, I used the framework of the Revit model to get started, and then added more information.

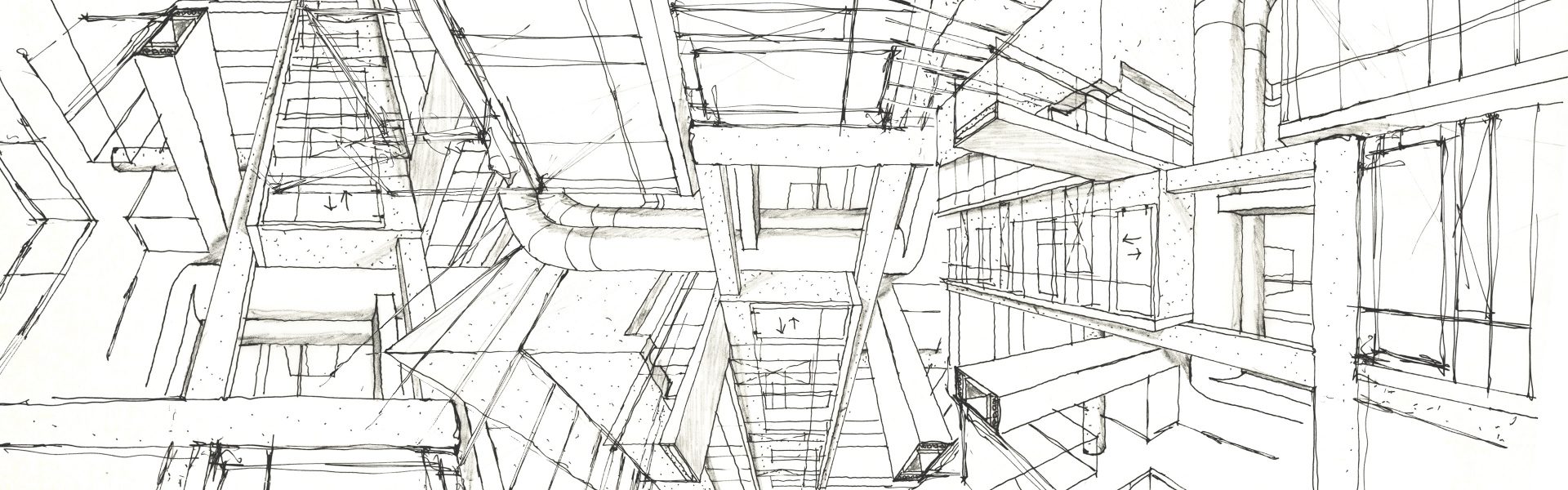

First I created the view I wanted in Revit, using a section box in a perspective view. I printed this big enough to draw over comfortably, and started adding layers of trace. (Every layer got taped down; I didn’t want anything to move, and this drawing wound up taking me two days.)

Using red pencil, I sketched out the basic geometry of the main masses I planned to add – the major ducts, mechanical equipment, and lights. Being rigorous about constructing my perspective from vanishing points was a big help here.

On the next layer of trace, I inked the image using Micron felt tip pens. I use four or five weights, and I start with a “mockup” of pen weights:

The pen work is all about moving slowly. I started from the foreground and worked backward “into” each space. This ensured I wouldn’t draw “over” something which belonged in the foreground. For tricky parts, I drafted in red pencil on the final sheet, just before inking it.

After about a day, I was done inking. Compare to my concept sketch on my sketchbook at right:

I let it dry thoroughly, then carefully erased all the pencil from the inking sheet and taped it to a white piece of paper from the recycle bin to ensure a good scan. At this point the work is about 2/3 done.

I scanned at 600dpi in grayscale, not black and white. Grayscale is much better for scanning linework sketches; notice how the black-and-white scan below removes detail from the thinner lines and edges.

Instead, my first act in Photoshop is to create a curves-type modification layer and place it over the linework. This gives me the control to clean up the background noise from the paper, while retaining all the detail in the linework, which is important if the image is ever used in print.

Then I color the image using a layer for each color. I paint bucket the entire layer with a highly saturated version of the color I want to use, and then set the layer transparency to tone down the color to what I want. This allows me to use the same color at different intensities on different layers easily – I can use the dropper and paint bucket to transfer a color from one layer to another, while maintaining different saturation on each.

With the full layer made, I use a layer mask to show the color only in the areas I want, then set the color layers to ‘Darken’ mode. This hides the edge of the color inside the black pixels of the scanned linework.

The colors, without the linework, look like this:

I used that same technique even gradients like the sky. The gradient in the layer extends all across the whole image, but is blocked by the layer mask where I don’t want it. Separating the content (color / gradient in the layer) from the boundaries (layer mask) is key to making this whole process managable (and editable in the future). It’s also possible to subtract layer masks from current selections as I work, releiving me of the tedius work of tracing over an edge I’ve already traced.

I also used layers of white to lighten linework and colors seen through glass.

At the end, the image is high-resolution enough to be used as a close-up of the cleanroom…

… or as a context image for its location in the project.

(Sharp eyes will notice the addition of a student in the viewing corridor not present in the original ink. I drew that person later on a separate bit of trace, then scanned and added the figure as its own linework layer over a white mask layer.)